Immer Weiter – Fragen und Antworten, Teil 4: Handel und Handelswaren

Bart Holterman, 12 October 2023

(for English, see below)

In diesem vierten Teil der Reihe, in der wir Fragen von Besuchenden der Ausstellung „Immer Weiter – die Hanse im Nordatlantik“ beantworten, haben wir Fragen gebündelt, die über Handelswaren gehen.

Wird heute noch immer Stockfisch gegessen?

Ja, Stockfisch wird immer noch vor allem in Norwegen hergestellt und von dort auch exportiert. In einzelnen europäischen Regionen gibt es bestimmte Zubereitungsarten, die durch lokale Gruppen als kulinarisches Erbe gepflegt werden. Ein Beispiel ist die „Stockfischbrüderschaft“ (Confraternita del Bacalà alla Vicentina) in der italienischen Region Venetien. Überraschenderweise ist vor allem Nigeria heutzutage ein wichtiger Absatzmarkt für Stockfisch. In Portugal und Spanien ist zudem der gesalzene und getrocknete Dorsch, ähnlich wie der Fisch der in der Frühen Neuzeit in Shetland hergestellt wurde, unter dem Namen Bacalhau/Bacalao ein wichtiger Bestandteil der nationalen Küche.

Kommt Butter heute noch immer aus Schottland?

Butter wird heute noch immer in Schottland produziert, aber die Qualität hat sich seit der Frühen Neuzeit deutlich verbessert. In Gegensatz zu irischer Butter wird sie allerdings nur wenig ins Ausland exportiert.

Wie viele Knochen gibt es in der Ausstellung?

Genau haben wir das nicht gezählt, aber es gibt viele Knochen, vor allem von Fischen, an unterschiedlichen Stellen in der Ausstellung. Knochen sind sehr wichtig als archäologisches Fundmaterial, weil sie uns über die Ernährungsgewohnheiten der Menschen in der Vergangenheit erzählen.

Werden auch Knochenreste bei den Wracks gefunden?

Ja, zum Beispiel sind im Wrack der Darßer Kogge Fischknochen und ein Rentiergeweih gefunden worden, diese gehörten zur Ladung des Schiffes. Ob die Fische für den Verzehr an Bord oder als Handelsware mitgenommen wurden, lässt sich jedoch nicht mehr eindeutig feststellen.

Wie viele Fässer waren auf der Bremer Kogge?

Nur ein kleines, das mit Teer gefüllt war. Die Kogge ist noch im Bau gesunken und war deswegen nie als Frachtschiff im Einsatz. An Bord von anderen Schiffswracks werden jedoch manchmal hunderte Fässer gefunden. Wie viele Fässer an Bord der Bremer Kogge gepasst haben, ist schwierig zu sagen, da es Fässer in den unterschiedlichsten Größen gab.

Wofür wurde das minderwertige Salz benutzt?

Salz war im Mittelalter nicht immer leicht zugänglich und musste aus unterirdischen Speichern (wie z.B. in Lüneburg) abgebaut, durch Verdünstung von Meereswasser (wie z.B. das spanische und französische Baiensalz) oder durch die Verbrennung von salzhaltigem Torf hergestellt werden. In manchen Fällen waren viele Reststoffe im Salz enthalten, was bei der Konservierung von Lebensmitteln mit Salz auf Dauer zum Verderben führen könnte. Deswegen wurde bei der Trockenfischherstellung nur möglichst reines Salz verwendet. Das übrige Salz konnte jedoch noch als günstiges Kochsalz, in chemischen Prozessen oder in der Medizin verwendet werden.

Mit welcher Währung wurde gehandelt zwischen den Ländern?

Shetland und Orkney hatten keine eigene Münze, und deswegen bezahlten die ausländischen Kaufleute dort mit ihrer eigenen Währung. Eine Auswahl an schottischen, niederländischen und deutschen Münzen, die in Shetland gefunden wurden, ist in der Ausstellung zu sehen. In Schriftquellen wird oft mit rix dollar (Reichstaler) gerechnet, aber es ist nicht genau zu sagen, ob hiermit auch bezahlt wurde; möglicherweise diente sie nur als Rechenwährung.

English version

In this fourth part of the series, in which we answer questions of visitors of the exhibition „Immer Weiter“, we have collected questions about trade and commodities.

Is stockfish still being eaten today?

Yes, stockfish is still being produced, mainly in Norway, and exported from there. In some European regions certain traditional recipes for cooking stockfish exist, which local groups cherish as a culinary heritage. An example is the „stockfish confraternity“ in the region Veneto in Italy, the Confraternita del Bacalà alla Vicentina. Surprisingly, today one of the most important export markets for stockfish is Nigeria. And in Portugal and Spain the salted dried cod known as bacalhau/bacalao is an important element of the national cuisine. The salt fish produced in Shetland in the early modern period must have been very similar.

Is butter still being exported from Scotland?

Butter is still produced in Scotland these days, but the quality has improved much since the early modern period. In contrast with Irish butter, however, Scottish butter is not exported in large quantities.

How many bones are on display in the exhibition?

We haven’t counted them exactly, but many (fish) bones are exhibited in various displays. The reason is that animal bones are important archaeological evidence for the consumption habits of people in the past.

Are bones also found near shipwrecks?

Yes. For example in the wreck of the Darßer Kogge, fish bones and a reindeer antler have been found, which can be seen in the exhibition. These were part of the cargo of the ship. However, it is difficult to say whether the fish were intended for consumption on board or if they were a trading commodity.

How many barrels were there on the Bremen Cog?

Only a small barrel was found, which was filled with tar. The ship sank while it was still being constructed, and therefore it was never used as a cargo ship. But on board of other shipwrecks, hundreds of barrels are found sometimes. It is difficult to say how many barrels would fit into the cargo hull of the Bremen Cog, as barrels came in all kinds of sizes.

What was the low-quality salt used for?

Salt was a commodity that was not readily available in the Middle Ages, as it had to be mined from deposits in the ground (for example in Lüneburg), or it had to be destilled by evaporating sea water (the so-called Bay salt from Spain and France) or by burning peat with a high salinity. In some cases, many impurities remained in the final product, which could lead to the spoilage of commodities that were preserved with salt. For this reason, fish was only cured with very pure salt. The lower-quality salt could, however, still be used for various purposes: for cooking, in chemical processes or in medicine.

Which currency was used in the trade between the countries?

Shetland and Orkney did not have their own currency or mint, and therefore the foreign merchants paid there with their own currency. A selection of Scottish, Dutch and German coins that were found in Shetland is displayed in the exhibition. Written accounts often count in rix dollar (Reichstaler), but it is unclear whether this was only a currency used for calculation, or if these coins were actually used in the trade.

Posted in: Exhibition, General

Immer Weiter – Fragen und Antworten, Teil 3: das Kogge-Special

Bart Holterman, 3 August 2023

(for English see below)

Obwohl sich die Ausstellung „Immer Weiter“ nicht mit dem Schiffswrack die „Bremer Kogge“ beschäftigt, gibt es viele Besuchende, die Fragen zu diesem Objekt gestellt haben. In diesem dritten Teil unserer Fragen und Anworten-Reihe haben wir diese Fragen gebündelt.

Wie viel ist die Bremer Kogge wert?

Der Wert des Schiffes als einzigartiges Kulturerbe ist nicht in Geld auszudrücken. Für die historische Forschung ist sie unersetzlich und liefert noch immer neue Einsichten.

Wann wurden Schiffe erfunden?

Das ist nicht genau zu sagen und unterscheidet sich für unterschiedliche Regionen auf der Welt. Bereits in der Steinzeit wurden einfache Wasserfahrzeuge aus ausgehöhlten Baumstämmen benutzt. Das waren sogenannte Einbäume. Ein solcher Einbaum wurde z.B. in Pesse in den Niederlanden gefunden und wird auf ein Alter von etwa 8.000 Jahren geschätzt. Später hat man dann angefangen, größere und kompliziertere Wasserfahrzeuge zu bauen. Zum Beispiel kennen wir archäologische Funde von größeren Booten aus England, die über 3.500 Jahre alt sind und mit Paddeln fortbewegt wurden (Dover-Boot). Das Mittelmeer befuhr man schon vor über 3.300 Jahren mit größeren, gesegelten Schiffen (Uluburun Wrack) und die Ägypter kannten schon vor 4.500 Jahren große aus Holz gebaute Flussschiffen (Khufu Schiff).

Wird davon ausgegangen, dass bei der Bergung der Bremer Kogge alle Überreste geborgen wurden?

Obwohl man den Boden bei der Bergung intensiv abgesucht hat, ist es anzunehmen, dass nicht alles, was erhalten war, auch gefunden wurde. Das Schiff lag viele hunderte Jahre in einem Fluß, so können Teile an andere Orte stromabwärts verlagert worden sein, wo sie möglicherweise immer noch liegen.

Wie viele Schiffe werden im Jahr gefunden?

Das ist sehr unterschiedlich, es ist schließlich vom Zufall abhängig. Aber es werden durch Bauarbeiten in (ehemaligen) Hafenbereichen und in Flachwasser- und Offshoregebieten immer häufiger Schiffswracks und Teile von Schiffen gefunden.

Warum hat man die Kogge nicht vor 1962 gefunden?

Die Kogge war Jahrhundertelang im Sediment im Flussbett der Weser vergraben und wurde erst bei Baggerarbeiten für eine geplante Erweiterung des Bremer Hafens gefunden. Hätte man diese Pläne nicht gehabt, wäre die Kogge wohl nie oder erst viel später entdeckt worden.

Wie wurde das Schiff aus der Weser geholt?

Taucher haben das Schiff in Einzelteilen aus dem Flussbett geborgen; diese wurden später im Museum wieder zu einem Schiff zusammengebaut und konserviert.

Könnte man unter Wasser ein Schiff erkunden?

Ja, das geht sogar ohne zu tauchen: Mit einem Echolot oder einem Magnetometer ist es möglich, von einem Schiff aus Objekte unter Wasser zu finden und zu identifizieren. Mit einem Sedimentsonar kann man sogar Strukturen im Boden erkennen. Um ein genaueres Bild zu bekommen müssen Forschungstaucher dann allerdings unter Wasser eine archäologische Begutachtung oder sogar eine Grabung durchführen.

In wie viele Werften ist die Kogge eingelaufen?

Die Kogge war in ihrem Leben wahrscheinlich nur auf einer Werft, und zwar auf der, wo sie auch gebaut wurde. Es wird davon ausgegangen, dass das Schiff sich noch im Bau befand, als es gesunken ist, und deswegen auch nie als Handelsschiff über die Meere fuhr.

Wie viele Schiffswracks werden wir neben der Kogge noch finden? Werden diese hier anzusehen sein?

Das ist unmöglich zu sagen, aber sicher werden es noch einige sein. Auf dem Meeresboden liegen tausende Wracks verstreut, wovon die meisten noch nicht genau untersucht wurden. Bei Bauarbeiten in Hafenbereichen sind in den letzten Jahren zudem viele Schiffsreste gefunden worden, von denen einige jenen der Bremer Kogge ähnlich sind. Manche davon werden bestimmt in Museen zu sehen sein. Die Bergung, Konservierung und Präsentation eines Schiffswracks ist aber kompliziert, sehr kostspielig und beansprucht viel Platz, weswegen sie wahrscheinlich nur in Ausnahmefällen stattfinden wird.

War die Bremer Kogge ein Kriegsschiff?

Nein. Zwar wurden Handelsschiffe im Mittelalter oft zu Kriegszwecken genutzt und auch ausgerüstet, aber es gibt keine Hinweise dafür, dass dies auch bei der Bremer Kogge der Fall war.

English version

Although the exhibition „Immer Weiter“ is not concerned with the shipwreck known as the “Bremen Cog“, many visitors have left questions about the ship on our Q&A station. In this blogpost, we have bundled questions about the cog and maritime archaeology.

How much is the Bremen Cog worth?

The value of the ship as unique cultural heritage is priceless. For our understanding of history she is irreplaceable and continues to provide new insights.

When were ships invented?

It is not possible to give an exact answer and differs for different regions of the world. Already in the Stone Age simple vessels were used which were made from hollowed-out trees. These are known as dugout canoes. Such a dugout canoe was for example found in Pesse in the Netherlands, which is believed to be about 8,000 years old. Later people started to build larger and more complex vessels. For example there are archaeological finds of larger vessels from England, which were rowed with paddles (Dover Boat). On the Mediterranean larger sailing vessels were used as early as 3,300 years ago (Uluburun wreck) and the ancient Egyptians had large wooden river barges 4,500 years ago (Khufu ship).

Is it assumed that all remains of the Bremen cog have been salvaged?

Although the river bed has been meticulously searched when the ship was salvaged, it is likely that not all parts of the ship that were preserved have also been found. The ship was located in a river for many hundreds of years, so it is possible that parts were drifted further downstream, where they might still be waiting to be found.

How many ships are found each year?

This differs a lot per year, as it primarily depends on coincidence. However, due to construction works in (former) harbour areas and in shallow water and offshore areas, shipwrecks and parts of ships are being found in increasing numbers.

Why was the Cog not found before 1962?

The Cog was buried in the sediment of the river bed of the Weser for centuries and was only found during dredging works for a planned extension of the harbour of Bremen. The Cog would never have been found, had these plans not existed, or at least only much later.

How was the ship retrieved from the Weser?

Divers salvaged the ship from the river bed piece for piece; later these pieces were reassembled as a ship in the museum and conserved.

Is it possible to explore a ship under water?

Yes, even without diving: with a multibeam or sidescan sonar or magnetometer it is possible to find and identify objects under water from a ship. With a sub-bottom profiler it is even possible to recognise structures in the sediment. However, to get a better picture it is neccesary for divers to perform an archaeological survey or even an excavation under water.

How many shipyards did the Cog visit?

During her life the Cog was probably only on one shipyard: the one on which she was also built. It is assumed that the ship was still in the process of being built when she sank, and never sailed the seas as a cargo ship.

How many shipwrecks we will still find next to the Cog? Will these be shown here?

That is impossible to say, but certainly many ships will still be found in the future. There are thousands of wrecks scattered on the sea floor, of which most have not been explored in detail. Construction works in harbour areas have revealed many remains of ships, some of which are similar to the Bremen Cog. Some of them will certainly be displayed in museums. However, because the recovery, conservation and display of a ship wreck is complicated, very expensive and requires a lot of space, this will occur probably only in exceptional cases.

Was the Bremen Cog a warship?

No. Although it happened regularly in the Middle Ages that cargo ships were used and fitted out for military purposes, there are no indications that this was the case with the Bremen Cog.

Posted in: Exhibition, General

1294 trade privilege between Norway, Bremen and Baltic towns declared part of the register “Memory of the World”

Hans Christian Küchelmann, 14 June 2023

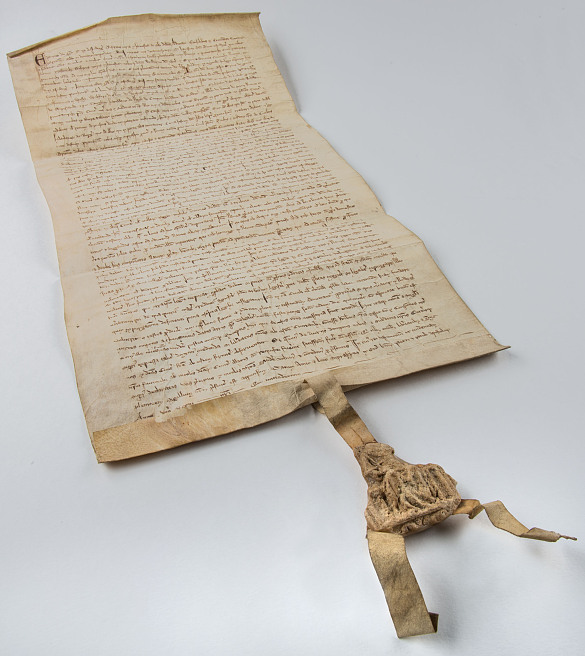

On the 18th of May 2023 the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) included 17 documents related to the Hanseatic League into the register “Memory of the World” (MOW). The documents stem from archives in six countries (Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Latvia and Poland). Documents from German archives are located in Braunschweig, Bremen, Hamburg, Köln and Lübeck. Particularly relevant for the Hanseatic North Atlantic trade is a trade privilege given by the Norwegian king to the town council of Bremen and the Baltic ports signed on the 6th of July 1294, the original of which is kept in the Staatsarchiv Bremen (signature StAB 1-Z 1294-Juli-6, see below). Likewise important are the legislative records of the Hanseatic League (Hanserezesse), which contain a lot of debates and decisions related to North Atlantic trade. The original copies of the Bremen town council from 1389-1517 are part of the MOW now as well.

For more information (in German) see:

Staatsarchiv Bremen

Posted in: Announcements, General

Immer Weiter – Fragen und Antworten, Teil 2

Bart Holterman, 23 May 2023

(for English see below)

Hier beantworten wir die Fragen, die Besuchenden der Ausstellung „Immer Weiter – Die Hanse im Nordatlantik“ gestellt haben. In diesem zweiten Teil geht es um die Fahrt zwischen Norddeutschland und den Inseln und das Leben an Bord.

Wie lange war man damals von Bremen nach Shetland unterwegs?

Die Dauer der Fahrt zwischen Norddeutschland und Shetland war stark vom Wetter abhängig, vor allem von der Windrichtung und -stärke. Einige Tage bis einer Woche war man jedoch sicher unterwegs. Der Bremer Schiffer Brüning Rulves beschreibt zum Beispiel in seiner Memoiren eine Reise von Bremen nach Shetland im Jahr 1551, die vier Tage im Anspruch nahm.

Wie sicher waren die Schiffe im Vergleich zu heutigen Schiffen? Gab es ein Rettungskonzept?

Obwohl die meisten seefahrenden Schiffe sehr stabil gebaut waren, war die Seefahrt sehr viel gefährlicher als heutzutage. Dabei war es nicht sosehr der Bau des Schiffes, sondern die Elemente, die die größte Gefahr darstellten. Das Risiko in einem Sturm zu geraten und Schiffbruch zu erleiden war reell. In so einem Fall gab es kein Rettungskonzept, und konnte man nur hoffen, es zu überleben.

Haben sich die Leute an Bord mal geprügelt?

Das Zusammenleben vieler Leute auf engstem Raum während eines langen Zeitraums führte selbstverständlich zu Spannungen und nicht selten auch zu Prügeleien. Unter anderem aus diesem Grund herrschte an Bord eine strikte Hierarchie, wobei der Kapitän die oberste Befehlsgewalt hatte. Laut dem hansischen Seerecht war es ihm erlaubt, seine Besatzungsmitglieder (einmal) zu schlagen. Trotzdem liefen solche Situationen manchmal aus dem Ruder, wie zum Beispiel bei dem Tod des Bremer Schiffers Cordt Hemeling in Shetland im August 1557.

Was hat man damals an Bord von Schiffen gegessen und getrunken?

Auf längeren Reisen konnten natürlich keine leicht verderbliche Nahrungsmittel mitgenommen werden. Deswegen hat man vor allem getrocknete oder gesalzene Lebensmittel gegessen, wie Schiffszwieback und gesalzenes Fleisch. Auch Stockfisch und getrocknete Erbsen und Bohnen werden regelmäßig in Proviantlisten erwähnt. Getrunken hat man dabei hauptsächlich Bier. In Rechnungen für Seereisen wird regelmäßig einen Unterschied zwischen Schiffsbier gemacht: Bier das man an Bord getrunken hat bzw. das als Handelsware dienende Bier.

English version

Here we answer the questions which were asked by visitors of our exhibition „Immer Weiter – Looking In From The Edge“. This second part bundles the questions about the journey between Northern Germany and the islands and life on board.

How long did it take to travel from Bremen to Shetland in those days?

The duration of a ship’s journey depended for a large degree on the weather conditions, especially the wind direction and speed. A couple of days until a week was a likely duration for the journey from Northern Germany to Shetland. For example, the skipper Brüning Rulves from Bremen mentions in his memoirs a journey from Bremen to Shetland in 1551 which lasted four days.

How secure were historical ships in comparison to modern ships? Was there a rescue plan?

Although most seagoing ships had quite sturdy constructions, seafaring in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period was much more dangerous than nowadays. It was not so much the construction of the ship, but the elements which were dangerous. There was a high risk of getting caught up in a storm and to suffer shipwreck. In those cases there were no rescue concepts; one could only hope to survive it.

Did the people on board fight now and then?

The cohabitation of many people in a cramped space during a large period of time of course led to tensions, and not rarely to violence. Among others for this reason, a tight hierarchy prevailed on board, with the highest authority in the hands of the captain. According to Hanseatic maritime law, he was allowed to hit the others on board (once) as a disciplinary measure. However, this didn’t prevent the violence getting out of hand sometimes, such as in the case about the death of Bremen skipper Cordt Hemeling in Shetland in August 1557.

What did they eat and drink on the ships back in the day?

Perishable foodstuffs of course could not be taken on long journeys. For this reason the people on board mostly lived on dried and salted food, such as ship biscuits and salted meat. Dried peas and beans and stockfish are other examples of food which are regularly listed as provision on ship journeys. It was mainly washed down with beer. Accounts for fitting out merchant ships regularly make the distinction between ship beer and merchant beer, of which the former was drunk on board, whereas the latter served as merchandise.

Posted in: Exhibition, General

Immer Weiter – Fragen und Antworten, Teil 1

Bart Holterman, 19 April 2023

(for English see below)

Am 23. März wurde im Deutschen Schifffahrtsmuseum die Ausstellung “Immer Weiter – Die Hanse im Nordatlantik” eröffnet. Am Ende dieser Ausstellung können Besuchenden Fragen über die Themen der Ausstellung hinterlassen. Nach fast einem Monat sind wir sehr erfreut über die große Zahl der Fragen, die dort gestellt wurden! Nun ist es Zeit, auf einige davon zu antworten. In dieser Post haben wir Fragen gebündelt, die mit Kommunikation und Alltag auf den Inseln zu tun haben.

Welche Sprache haben die Händler benutzt?

Im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert sprach man in Norddeutschland noch meistens Niederdeutsch, eine Sprache die noch heute als Plattdeutsch bekannt ist. Seit der Hansezeit war diese Sprache in großen Teilen Nordeuropas die internationale Handelssprache, vergleichbar mit Englisch heutzutage. Vor allem im Dänischen und Norwegischen sind noch viele niederdeutsche Leihwörter anzutreffen. Es ist daher anzunehmen, dass die deutschen Kaufleute in Shetland auch Niederdeutsch gesprochen haben, und dass dies von ihren Handelspartnern auch durchweg verstanden wurde. So gibt es Dokumente, die belegen, dass Shetländer gefragt wurden, deutschsprachige Dokumente für die schottische Verwaltung ins Englische zu übersetzen.

Andererseits hatten die deutschen Kaufleute wahrscheinlich durch ihre jahrzehntelange Anwesenheit auf den Inseln auch einige Kenntnisse der Sprache der Inselbewohner. Diese sprachen noch bis ins 18. Jahrhundert eine skandinavische Sprache, Norn genannt. Die Obrigkeit benutzte jedoch zunehmend die schottische Version des Englischen. Aus Briefen Bremer Kaufleute des späten 17. Jahrhunderts wissen wir, dass die deutschen Kaufleute auch Schreibfähigkeiten in dieser Sprache besaßen.

Im Handelsalltag wurden all diese Sprachen wahrscheinlich neben- oder durcheinander benutzt, je nachdem, mit wem man handelte.

Wurde Wissen über Sprache und Gepflogenheiten nur innerhalb der Handelsfamilie weitergegeben, oder gab es auch Schule?

Es gab sicher auch Schulen im Spätmittelalter und in der Frühen Neuzeit. Allerdings waren diese meistens darauf gerichtet, die lateinische Sprache zu lehren und für ein wissenschaftliches Studium oder Verwaltungsfunktionen vorzubereiten. Praktisches Wissen über den Handel wurde erworben, indem man in der Lehre bei einem Kaufmann ging. Dies musste aber nicht zwingend ein Mitglied der eigenen Familie sein. Aus Island wissen wir, dass angehende Kaufleute zudem einen Winter lang bei einer isländischen Familie verblieben, um so die Sprache und Sitten der zukünftigen Handelspartner kennenzulernen und zudem erste Handelskontakte zu knüpfen. Ob dies in Shetland auch der Fall war ist nicht bekannt, aber es wäre anzunehmen.

Wie haben die Bremer damals auf Shetland gelebt?

Die deutschen Kaufleute in Shetland hatten keine festen Häuser, wo sie gewohnt haben. Die einzigen Gebäuden, die sie benutzten, waren kleine Buden, die als Lager- und Verkaufsräume dienten. Vielleicht haben die Schiffer und Kaufleute auch in diesen Buden übernachtet, aber die restlichen Besatzungsmitglieder und Gehilfen schliefen an Bord der Schiffe, die in den Buchten vor Anker lagen. Hier lebten sie dicht aufeinander ohne viel Privatsphäre und durften nur von Bord, wenn der Schiffer es erlaubte. Dies wissen wir aus Streitfällen, wie z. B. dem über den Tod des Bremer Schiffers Cordt Hemeling, der im Sommer 1557 nach einer Prügelei an Bord starb.

Die vielen weiteren Fragen sind nächstes Mal daran!

The exhibition “Immer Weiter – Looking in from the Edge” was opened in the German Maritime Museum on 23 March. At the end of the exhibition, visitors have the possibility to ask questions about the topics of the exhibition. After almost a month we can say that we are positively surprised by the large number of questions asked! Now it is time, to start answering some of them. In this post we have bundled those questions, that have to do with communication and life on the islands.

Which language did the merchants use?

In the 16th and 17th century people in Northern Germany largely spoke Low German, a language that is still known as “Plattdeutsch” today. Since the Hanseatic period, this language was the universal language of trade for a large part of northern Europe, comparably to English today. Especially in Danish and Norwegian we can still find many Low German loanwords. We can thus assume that the German merchants in Shetland also spoke Low German, and that this was understood by their trading partners. For example, there are documents that attest that Shetlanders were asked to translate German letters into English for the Scottish authorities.

On the other hand, German merchants probably acquired some knowledge of the language of the islanders due to their decades-long contacts. They spoke a kind of Scandinavian language known as Norn until the 18th century. However, the authorities and the landowners used Scots, a variety of English, more and more. We known from late 17th-century letters of merchants from Bremen, that they possessed writing proficiency in Scots as well.

In the trading practice, all languages were probably used next to each other, depending on who the trading partners were.

Was knowledge about the language and customs only passed on within a merchant family, or was there also a school?

There certainly existed schools in the late Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, but these were mostly focused on teaching the Latin language and to prepare for scholarly studies or administrative roles. Practical knowledge about trading practices were transferred by entering into an apprenticeship with a senior merchant. This did not necessarily have to be a member of the own family, however. From Iceland we also know that there existed the practice that aspiring merchants would stay one winter with an Icelandic family to learn the language and customs of their future trading partners, and to establish a first trading network. Whether this was also the case in Shetland is not known, but it is very well possible.

How did the merchants from Bremen live in Shetland in those times?

The German merchants in Shetland did not possess houses in which they lived. The only buildings used by them were small booths, which served as storage facilities and shops. It is possible that the skippers and merchants also spent the night in those booths, but all the other crew members and servants slept on board the ships, which were at anchor in the bays of the islands. Here they lived closely together without much personal space or comfort. Moreover, they were only allowed to leave the ship with explicit permission of the skipper. We know this from cases in which this led to problems, for example the case about the death of skipper Cordt Hemeling from Bremen, who died in Summer 1557 after a violent confrontation with his crew members on board.

The many other questions will be answered next time!

Posted in: Exhibition, General