Immer Weiter – Fragen und Antworten, Teil 4: Handel und Handelswaren

Bart Holterman, 12 October 2023

(for English, see below)

In diesem vierten Teil der Reihe, in der wir Fragen von Besuchenden der Ausstellung „Immer Weiter – die Hanse im Nordatlantik“ beantworten, haben wir Fragen gebündelt, die über Handelswaren gehen.

Wird heute noch immer Stockfisch gegessen?

Ja, Stockfisch wird immer noch vor allem in Norwegen hergestellt und von dort auch exportiert. In einzelnen europäischen Regionen gibt es bestimmte Zubereitungsarten, die durch lokale Gruppen als kulinarisches Erbe gepflegt werden. Ein Beispiel ist die „Stockfischbrüderschaft“ (Confraternita del Bacalà alla Vicentina) in der italienischen Region Venetien. Überraschenderweise ist vor allem Nigeria heutzutage ein wichtiger Absatzmarkt für Stockfisch. In Portugal und Spanien ist zudem der gesalzene und getrocknete Dorsch, ähnlich wie der Fisch der in der Frühen Neuzeit in Shetland hergestellt wurde, unter dem Namen Bacalhau/Bacalao ein wichtiger Bestandteil der nationalen Küche.

Kommt Butter heute noch immer aus Schottland?

Butter wird heute noch immer in Schottland produziert, aber die Qualität hat sich seit der Frühen Neuzeit deutlich verbessert. In Gegensatz zu irischer Butter wird sie allerdings nur wenig ins Ausland exportiert.

Wie viele Knochen gibt es in der Ausstellung?

Genau haben wir das nicht gezählt, aber es gibt viele Knochen, vor allem von Fischen, an unterschiedlichen Stellen in der Ausstellung. Knochen sind sehr wichtig als archäologisches Fundmaterial, weil sie uns über die Ernährungsgewohnheiten der Menschen in der Vergangenheit erzählen.

Werden auch Knochenreste bei den Wracks gefunden?

Ja, zum Beispiel sind im Wrack der Darßer Kogge Fischknochen und ein Rentiergeweih gefunden worden, diese gehörten zur Ladung des Schiffes. Ob die Fische für den Verzehr an Bord oder als Handelsware mitgenommen wurden, lässt sich jedoch nicht mehr eindeutig feststellen.

Wie viele Fässer waren auf der Bremer Kogge?

Nur ein kleines, das mit Teer gefüllt war. Die Kogge ist noch im Bau gesunken und war deswegen nie als Frachtschiff im Einsatz. An Bord von anderen Schiffswracks werden jedoch manchmal hunderte Fässer gefunden. Wie viele Fässer an Bord der Bremer Kogge gepasst haben, ist schwierig zu sagen, da es Fässer in den unterschiedlichsten Größen gab.

Wofür wurde das minderwertige Salz benutzt?

Salz war im Mittelalter nicht immer leicht zugänglich und musste aus unterirdischen Speichern (wie z.B. in Lüneburg) abgebaut, durch Verdünstung von Meereswasser (wie z.B. das spanische und französische Baiensalz) oder durch die Verbrennung von salzhaltigem Torf hergestellt werden. In manchen Fällen waren viele Reststoffe im Salz enthalten, was bei der Konservierung von Lebensmitteln mit Salz auf Dauer zum Verderben führen könnte. Deswegen wurde bei der Trockenfischherstellung nur möglichst reines Salz verwendet. Das übrige Salz konnte jedoch noch als günstiges Kochsalz, in chemischen Prozessen oder in der Medizin verwendet werden.

Mit welcher Währung wurde gehandelt zwischen den Ländern?

Shetland und Orkney hatten keine eigene Münze, und deswegen bezahlten die ausländischen Kaufleute dort mit ihrer eigenen Währung. Eine Auswahl an schottischen, niederländischen und deutschen Münzen, die in Shetland gefunden wurden, ist in der Ausstellung zu sehen. In Schriftquellen wird oft mit rix dollar (Reichstaler) gerechnet, aber es ist nicht genau zu sagen, ob hiermit auch bezahlt wurde; möglicherweise diente sie nur als Rechenwährung.

English version

In this fourth part of the series, in which we answer questions of visitors of the exhibition „Immer Weiter“, we have collected questions about trade and commodities.

Is stockfish still being eaten today?

Yes, stockfish is still being produced, mainly in Norway, and exported from there. In some European regions certain traditional recipes for cooking stockfish exist, which local groups cherish as a culinary heritage. An example is the „stockfish confraternity“ in the region Veneto in Italy, the Confraternita del Bacalà alla Vicentina. Surprisingly, today one of the most important export markets for stockfish is Nigeria. And in Portugal and Spain the salted dried cod known as bacalhau/bacalao is an important element of the national cuisine. The salt fish produced in Shetland in the early modern period must have been very similar.

Is butter still being exported from Scotland?

Butter is still produced in Scotland these days, but the quality has improved much since the early modern period. In contrast with Irish butter, however, Scottish butter is not exported in large quantities.

How many bones are on display in the exhibition?

We haven’t counted them exactly, but many (fish) bones are exhibited in various displays. The reason is that animal bones are important archaeological evidence for the consumption habits of people in the past.

Are bones also found near shipwrecks?

Yes. For example in the wreck of the Darßer Kogge, fish bones and a reindeer antler have been found, which can be seen in the exhibition. These were part of the cargo of the ship. However, it is difficult to say whether the fish were intended for consumption on board or if they were a trading commodity.

How many barrels were there on the Bremen Cog?

Only a small barrel was found, which was filled with tar. The ship sank while it was still being constructed, and therefore it was never used as a cargo ship. But on board of other shipwrecks, hundreds of barrels are found sometimes. It is difficult to say how many barrels would fit into the cargo hull of the Bremen Cog, as barrels came in all kinds of sizes.

What was the low-quality salt used for?

Salt was a commodity that was not readily available in the Middle Ages, as it had to be mined from deposits in the ground (for example in Lüneburg), or it had to be destilled by evaporating sea water (the so-called Bay salt from Spain and France) or by burning peat with a high salinity. In some cases, many impurities remained in the final product, which could lead to the spoilage of commodities that were preserved with salt. For this reason, fish was only cured with very pure salt. The lower-quality salt could, however, still be used for various purposes: for cooking, in chemical processes or in medicine.

Which currency was used in the trade between the countries?

Shetland and Orkney did not have their own currency or mint, and therefore the foreign merchants paid there with their own currency. A selection of Scottish, Dutch and German coins that were found in Shetland is displayed in the exhibition. Written accounts often count in rix dollar (Reichstaler), but it is unclear whether this was only a currency used for calculation, or if these coins were actually used in the trade.

Posted in: Exhibition, General

How to recognise stockfish from its bones

Bart Holterman, 22 December 2016

For most readers of our blog, probably the most mysterious part of our research is the work of Hans Christian Küchelmann, archaeozoologist, who uses archaeological finds of fish bones as traces of the late medieval North Atlantic (stock)fish trade. A fish bone found in the ground, however, does not say where the fish once came from or to which fish it belonged. So, how can one identify a stockfish merely by its bones? This blog post will shed a light on that mysterious procedure.

1. Stockfish production

In order to be able to identify a stockfish bone, it is essential to know how stockfish was produced. Luckily, stockfish is made in Iceland and Northern Norway to this day in ways that have hardly changed over the centuries, so in combination with historical sources, we can reliably reconstruct what a medieval stockfish must have been like.

Stockfish is made in polar regions from fish from the Gadidae family where they are hung to dry outside during the winter. Due to climatic conditions this is only possible in arctic regions as the cool weather prevents the fish from rotting before it dries. However, the entrails must be removed before the fish is hung to dry, and the heads are cut off. This is roughly done with two methods: a) the fish is gutted and beheaded, the rest of the body left intact (rundfisk), or b) the fish is beheaded and split in two, removing the entrails as well as most of the spinal column, and then hung to dry. The latter method is called råskjær in Norwegian (rotscher in the Low German medieval documents). As this leaves only a few caudal (tail) vertebrae in the stockfish, most bones of stockfish will come from rundfisk.

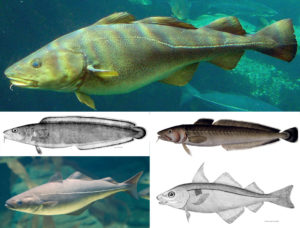

2. Species and distribution

Different species of the Gadidae family used in the production of stockfish. Clockwise, starting at the top: cod (Gadus morhua), ling (Molva molva), haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus), pollock (Pollachius virens), tusk (Brosme brosme). images: Wikimedia Commons

As mentioned, stockfish was made from species of the Gadidae family. A trained eye will have no problem recognising a bone from a Gadidae fish in most cases. Due to long travel times and the absence of freezers in pre-industrial times, these fish could only be transported in preserved form, either salted or dried. Hence, a find of a Gadidae bone, especially on inland sites, hints at having belonged to a stockfish.

However, in coastal areas these fish were also eaten fresh, so how do you know a bone is from stockfish in that case? It is necessary to look at the distribution of the different Gadidae species. Three of the species that were used for producing stockfish, namely saithe (Pollachius virens), ling (Molva molva), and tusk (Brosme brosme) do not appear in the Southern North Sea and Baltic Sea. Bones from these three species found on the European mainland, especially in inland areas, are therefore a strong indicator for stockfish.

3. Size

By far most of the stockfish, however, is and was made from cod (Gadus morhua), which does live in the Southern North Sea and the Baltic Sea. Bones of cod could therefore also belong to locally caught (and therefore not dried) fish. So we need another indicator to distinguish a stockfish from fresh local cod. The cod which live around the German shores are mostly smaller juveniles, older and larger fish live further North. By comparing the size of the bones to those of complete skeletons it is possible to estimate the size of the fish they belonged to. Bones belonging to fish larger than c. 75cm are less likely to have been local catch and were probably imported in dried form. Moreover, a high prevalence of fish in a specific size range is an indicator of stockfish, as these were sorted and sold according to size, whereas local catches will likely show a higher variety of fish in different sizes.

4. Bone composition

Because the head of the fish was cut off and remained at the production site one can expect head bones to be absent at consumption sites. Indeed, we find a clear overrepresentation of post-cranial (i.e. bones not belonging to the head, from cranium: head) bones on some sites in mainland Europe. On some archaeological sites in Iceland, for example, there are almost only cranial bones which is a clear sign that stockfish was produced there.

Archaeological finds of cod bones (brown), compared to modern bones (white). The cleithra (top), which are located directly behind the head of the fish, but remain when the fish is beheaded, clearly belong to larger individuals and are systematically cut off on the right, indicative of stockfish production. Image: Hans Christian Küchelmann

5. Cutting and hammering marks

The production and consumption of stockfish can also leave traces on the bones themselves. For example, the heads of fish were chopped of in a standardised way, leaving clear-cut chopping edges on the bones of the shoulder girdle directly behind the head. Also, the preparation of stockfish required hammering the fish for a while before soaking it, to make the flesh softer. As we have seen from our own experiences in preparing stockfish, this procedure can destroy or deform the vertebrae of the fish. Hence, deformed or broken vertebrae can be a sign of stockfish consumption in the archaeological record.

6. Isotope and aDNA analysis

Further, more advanced evidence from the North Atlantic stockfish trade can be acquired by applying methods such as aDNA analysis and isotope analysis, which can potentially retrace the remains of an animal to the area in which it lived. However, an explanation of these techniques might be a topic for a next post.

Further reading

Barrett, James H. (2009): Cod bones and commerce: the medieval fishing revolution. – Current Arrchaeology 221, 20-25

Heinrich, Dirk (1986): Fishing and the Consumption of Cod (Gadus morhua Linnaeus, 1758) in the Middle Ages. in: Brinkhuizen, Dick Constantijne & Clason, Anneke T. (eds.): Fish and Archaeology.

Ólafsdottir, Gudbjörg Ásta / Westfall, Kristen M. / Edvardsson, Ragnar / Pálsson, Snæbjörn (2014): Historical DNA reveals the demographic history of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) in medieval and early modern Iceland. – Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 281

Orton, David C. / Morris, James / Locker, Alison / Barrett, James H. (2014): Fish for the city: meta-analysis of archaeological cod remains and the growth of London’s northern trade. – Antiquity 88, 516-530

Posted in: General

Medieval Stockfish recipe: Stockfish with peas, apple, and raisins

Bart Holterman, 14 July 2016

On the 11th of June 2016, a “Gastronomic stockfish symposium” took place in the city of Bergen, Norway, during the International Hanseatic Days 2016. The symposium highlighted the important role of dried fish for the history of the city. After all, without the high demand for stockfish in pre-modern Europe the city would probably never have become the medieval and early modern trading hub for northern Europe. Until c. 1500 stockfish coming from northern Norway and Iceland was brought to Bergen, and from there traded with merchants from the European mainland and the British islands, in exchange for grain and other commodities. This led to the establishment of the Hanseatic Kontor, the remains of which still exist as the Tyskebrygge quarter in the city, dominated by merchants from Lübeck, who had a near monopoly on the stockfish trade for centuries.

Topics during the symposium were very diverse, illustrating the multi-faceted influence of stockfish on the economy and culinary culture of Norway and the rest of Europe, in the past and today. The papers presented ranged from the influence of climate change on cod stocks to the culinary stockfish traditions on the Iberian peninsula, in Upper Franconia, and in Northern Italy. In the latter case, there even exists a stockfish brotherhood which seeks to preserve the culinary stockfish tradition in Italy. All presentations (with pdf files and videos) can be found here. I presented the stockfish consumption in medieval Germany, combining Hans Christian Küchelmann’s archaeozoological research and my own, based on written sources such as cook books.

This provides the perfect opportunity to present another medieval stockfish recipe which we tested a while ago: stockfish with peas, apple and raisins. As the name suggests, the recipe is an example of the same typical medieval combination of hearty and sweet tastes which was also prevalent in the previous recipe of Spanish puff pastry, and which might seem peculiar to modern taste. It is derived from a fifteenth-century manuscript from Flanders which is being edited by Christianne Muusers on her wonderful website Coquinaria. She interpreted the recipe as a typical winter recipe, since all ingredients were available in dried form at the time. We took fresh or deep-frozen ingredients (except for the stockfish), which tasted just as well. For Muuser’s transcription and interpretation of the recipe, see this page.

Cooking time: ca. 1 hour (+ 1,5 day preparation)

Ingredients (2-3 persons):

- 100g stockfish (makes about 200g fish meat when soaked an cleaned)

- 200g peas

- butter

- 1 apple, in pieces

- 1 large onion, sliced

- 100g raisins

- pepper

- cardamom

- mixture of cinnamon, cloves, and mace (or nutmeg)

- ginger powder

Preparation:

- Hammer the stockfish well for a while (if needed: some stockfish is sold pre-hammered). Soak the fish in water for 1-2 days, refresh the water a couple of times a day. When the fish is well soaked, remove the skin and bones. Take care to remove all the small bones!

- Fry the onion until golden. Add the apple and stockfish pieces and let it fry for a while, then sprinkle the spices over it.

- Add the peas and some water, stir and let it simmer with a closed lid on low fire, 20-30 minutes.

- Add the raisins during the last 10 minutes.

- Serve hot.

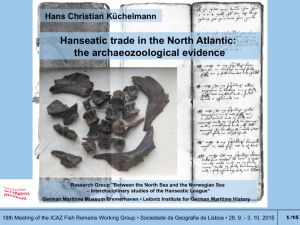

Project presentation at the 18th Meeting of the ICAZ Fish Remains Working Group (FRWG) in Lisbon

Hans Christian Küchelmann, 8 January 2016

On the 30th of September I held a presentation at the 18th Meeting of the Fish Remains Working Group in Lisboa. The Fish Remains Working Group (FRWG) is a subject specific working group of the International Council for Archaeozoology (ICAZ), operating since 1980 with regular biennial research meetings and publications on archaeological fish remains. Its 18th meeting was entitled “Fishing through Time – Archaeoichthyology, Biodiversity, Ecology and Human Impact on Aquatic Environments” and was held in the Museu da Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa from the 28th of September to the 3rd of October 2015. For further information on the programme of the conference see the book of abstracts.

On the 30th of September I held a presentation at the 18th Meeting of the Fish Remains Working Group in Lisboa. The Fish Remains Working Group (FRWG) is a subject specific working group of the International Council for Archaeozoology (ICAZ), operating since 1980 with regular biennial research meetings and publications on archaeological fish remains. Its 18th meeting was entitled “Fishing through Time – Archaeoichthyology, Biodiversity, Ecology and Human Impact on Aquatic Environments” and was held in the Museu da Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa from the 28th of September to the 3rd of October 2015. For further information on the programme of the conference see the book of abstracts.

The theme of the conference fit perfectly to one of the research goals of our project, which I presented within the session “Multi-disciplinary Approaches to the Study of Fish Remains: Archaeology, written and illustrated Sources”. My presentation was entitled “Hanseatic trade in the North Atlantic: the archaeozoological evidence” and its main aim was to introduce our new research project to the archaeo-ichthyiological community, to inform about the historical background, to present an overview of the evidence accumulated so far, to show the potentials and limitations of the data, and to present preliminary results.

The conference was a fantastic opportunity to get in contact with colleagues working on related topics. For example Jennifer Harland or Rebeccca Nicholson, who are working on fish remains from medieval sites in Scotland and Orkney, James Barrett who analysed the fish bones from the wreck of the Mary Rose (AD 1545), Lembi Lougas who presented material from two hanseatic wrecks in Tallinn, and Jan Bakker, who prepared a poster on fish remains from the hanseatic city of Cologne. Most important was a meeting with James Barrett, head of the international project “The Medieval Origins of Commercial Sea Fishing”, based in Cambridge. We discussed the possibilities for future cooperation between the two projects.

Apart from the scientific part, the organisers provided a fantastic field trip, which included a visit to the fish market of Setubal.

A tusk (Brosme brosme) at the fish market of Setubal. The tusk is one of the species prepared as stockfish in the North Atlantic and traded by Hanseatic merchants, although not in large quantities. Remains have been found for instance in medieval Duisburg. Photo: Hans Christian Küchelmann

Posted in: Reports