Keeping the Faroese bishop warm – how a tiled stove tells the story of the Reformation in the Faroes

Natascha Mehler, 16 August 2017

with Torbjörn Brorsson, Martina Wegner and Símun V. Arge

In 1557 the Reformation in the Faroes came to an end when the Faroese bishopric at Kirkjubøur was abolished and its properties confiscated by Christian III of Denmark. This was the result of a process which started in 1539 when Amund Olafson, the last Catholic bishop, was replaced by Jens Gregersen Riber, the first Lutheran bishop of the Faroes. Jens Riber stayed at Kirkjubøur until 1557 when he left to take on a new position in Stavanger. We know very little about the lives of these two bishops. However, during archaeological excavations conducted in 1955 at the site of the former episcopal residence, the remains of a tiled stove dating to the early and mid-16th century came to light which add knowledge about the daily life at Kirkjubøur.

The tile fragments were now, more than 60 years after their discovery, analyzed as part of this research project. Tiled stoves were a luxurious rarity in the North Atlantic islands. In Iceland, for example, 16th-century tiled stoves are only known from the two bishoprics at Skálholt and Hólar, the Danish residence at Bessastaðir and from the monastery at Viðey. The Kirkjubøur fragments are the only remains of a tiled stove in the Faroes. In Denmark or Northern Germany, however, tiled stoves were rather common in burgher households and those of the nobility.

19 stove tile fragments were found at Kirkjubøur, all made from red clays, moulded with relief decoration and applied with a white slip and green lead glaze. Varying fabric and decoration indicates that the tiles are the products from at least two different workshops. This means that either the tiles of the former stove were exchanged during its lifetime, or the stove was made from tiles from different workshops. The latter interpretation would be rather unusual in a continental context but all known early modern tiled stoves from Iceland were made of tiles from different workshops because access, import and maintenance were very difficult.

Stove tile made near Lübeck, with the remains of Judith and the head of Holofernes (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

The images on the Kirkjubøur tiles mirror the struggles of the introduction of the Reformation in the Faroes. All tiles show Christian or biblical motifs and themes, but while one of the identified motifs displays catholic imagery, others are clearly reformist in meaning. In many Northern European households such stove tiles decorated with Lutheran imagery were indeed used as a medium to express the Lutheran confession.

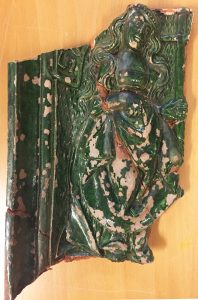

Stove tile produced in the area between Lübeck and Bremen, with the relief of probably a female Saint (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

One stove tile fragment shows a female figure with a cross in her left hand. A letter “S” is preserved, suggesting that this is a female saint such as Helena. If this interpretation holds true it would be a tile with purely Catholic imagery. The best preserved stove tile shows a bearded man in profile and the words [S]ANT PAVLO APOSTOLVS. Although this is a depiction of yet another saint – and thus rather Catholic in meaning – the letters of Paul the Apostle were often invoked by reformist theologians of Wittenberg. All other identified motifs were popular amongst supporters of Lutheranism. One fragment shows the lower body part of a female figure with a man’s head next to it. This is clearly a depiction of Judith with the head of Holofernes in her hand, a widespread stove tile motif in Lutheran contexts. And two identical tiles show the ascension of Jesus and parts of the creed of the Lutheran catechism. The surviving text reads 6 ER IST AVGEFARE[N] GEN HIMEL SITZET ZVR RECHTEN GOTES DES ALMECHTIGEN VATERS (transl. “he has ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of the Father”). The letter 6 indicates that this is the sixth stove tile in a series.

Eight fragments of these stove tiles were selected for analysis by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MA/ES), a standard method in ceramic analysis, carried out by Torbjörn Brorsson (Kontoret för Keramiska Studier). The main goal of the analysis was to determine the chemical composition of the various fabrics, with the aim to identify the workshops which produced these tiles. The results show that the tile with Paul the Apostle was made in Lübeck, and the tile with Judith and Holofernes, as well as the tile with the creed of the Lutheran catechism, in the surroundings of Lübeck. The tile with the female saint was made in the area between Lübeck and Bremen, which also includes Hamburg. This is no surprise; Northern German potters were the leading craftsmen to supply the Northern European market with stove tiles at that time.

The stove tiles were imported to the Faroes during the period when the Faroes were licensed to Hamburg citizen Thomas Koppen, between 1529 and 1553. Thomas Koppen was Oberalter of the churches in Hamburg and therefore an important figure in the process of the Reformation there. Maybe Koppen’s merchants (very likely he never visited the Faroe Islands himself) had brought the tiles from Lübeck via Hamburg to the Faroes. It is also very likely that Norwegian merchants from Bergen brought the tiles to the Faroes. The islands were closely connected to Bergen, with many ships travelling between the harbours of Tórshavn and Bergen. Lübeck merchants held a very important position in Bergen at that time and the tiles could have been brought from Lübeck first to Bergen and then went further to the Faroes.

The story that the tile finds suggest is such: a tiled stove was first erected at Kirkjubøur during the office of the Catholic bishop Amund Olafson, and fitted with tiles such as the one with the female saint. When Jens Riber took over as first Lutheran bishop in 1539 he bought new tiles from a different workshop and exchanged the purely Catholic images on his stove with motifs of the new faith. Only then could he enjoy the comforting warmth effusing from his stove without being agonized by the troubling sight of Catholic images.

References:

Julia Hallenkamp-Lumpe, Das Bekenntnis am Kachelofen? Überlegungen zu den sogenannten “Reformationskacheln”. In: C. Jäggi and J. Staecker (eds.), Archäologie der Reformation. Studien zu den Auswirkungen des Konfessionswechsels in der materiellen Kultur (Berlin 2007) 239–258.

Louis Zachariasen, Føroyar sum rættarsamfelag 1535–1655 (Tórshavn 1961), see pages 161–184.

Sailors, merchants and priests: people on board the ships heading North

Bart Holterman, 13 May 2016

The general history of the northern German trade with the North Atlantic is relatively well known but we know very little about the persons involved in this trade. This is especially true for the men that manned and sailed the ships that headed North.

Luckily, there are a couple of sources pertaining to the North Atlantic trade that give us a good insight into the people on board the ships. First, two boarding lists from Oldenburg for ships trading with Iceland in the 1580s have survived. Second, there is the magnificent book of donations of the Hamburg confraternity of St Anne, the socio-religious organisation behind the trade with Iceland, Shetland, and the Faroe Islands. From the 1530s onwards, the register lists the alms spent to the confraternity by the people on board of nearly every ship that returned to Hamburg, resulting in a more or less complete register of boarding lists.

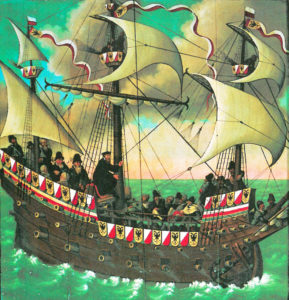

On board a sixteenth-century ship: detail of the epitaph for the ship´s priest Sweder Hoyer (deceased 1565) from the St Jacob church in Lübeck. Note: this image does not necessarily reflect the situation on board the merchant ships in the North Atlantic.

From these sources we can learn that the number of people on board varied greatly, ranging from 77 on larger ships up to around 10 on board the smallest vessels. For Iceland, it was not uncommon to have more than 25 people on board. Ships sailing to Shetland and the Faroe Islands had less people on board, usually 15-20.

This difference in number of people on board was mainly caused by the number of merchants on board. The sizes of the crews were relatively similar on each ship, because 10 to 15 people were needed to sail the ship, regardless of its size. A typical crew consisted of:

– Skipper (schipper). He was the captain, the leader of the ship, often also one of the merchants, and (partly) shipowner.

– Helmsman (sturman), the one who steered the ship and had navigational knowledge.

– Chief boatswain (hovetbosman), the leader of the sailors.

– Schimman, the officer responsible for rigging and other technical things.

– Cook (koch).

– Carpenter (tymmerman), responsible for repairs to the ship.

– Gunner (buchsenschut), responsible for the defense of the ship.

– Barber (bartscher), who had medical knowledge, but lacked on most ships.

– 2-4 sailors (bosman).

– 1-2 ship boys (putker), young sailors in training.

Besides these, ships transported merchants and their servants, falcon catchers, priests, and passengers from the islands which used the regular traffic to travel to and from the European mainland.

Further reading:

B. Holterman, Size and composition of ship crews in the German trade with the North Atlantic islands. In: N. Mehler (ed.), Traveling to Shetland, Faroe and Iceland in the early modern period (Leiden, in press).

F. C. Koch, Untersuchungen über den Aufenthalt von Isländern in Hamburg für den Zeitraum 1520-1662. Beiträge zur Geschichte Hamburgs 49 (Hamburg 1995).

Study course “Networking Europe: Art and Cultural History of the Hanse”

Bart Holterman, 9 November 2015

In September 2015 I took part in the study course “Networking Europe: Kunst- und Kulturgeschichte der Hanse”, organised by the Warburghaus, University of Hamburg. The course, led by Profs. Barbara Welzel (University of Dortmund) and Iris Wenderholm (University of Hamburg), offered the ten participants, predominantly PhD students in art history, a platform to present their research and to discuss methodological questions.

Hans Kemmer, Portrait of the merchant Hans Sonnenschein (1534), St. Annen Museum, Lübeck. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

The course started with a visit to the opening of the exhibition “Lübeck 1500: Kunstmetropole im Ostseeraum” in the Museumquartier St. Annen in Lübeck. The exhibition highlighted the central role of Lübeck in the late Middle Ages as a centre for the production and trade of (religious) art. It presented an extraordinary and impressive overview of this period, with many loans from museums abroad.

The historical perspective was assumed with a subsequent visit to the newly opened European Hanse Museum (Europäisches Hansemuseum), through which we were guided by Prof. Rolf Hammel-Kiesow, the museum’s scientific leader. The museum provides a fascinating overview of the history of the Hanse in different environments (e.g., the mouth of the river Neva, where the Novgorod traders assembled, the market of Bruges, etc.) which submerge the visitor in the time of the Hanse, while supporting this with copies of archival documents and other sources.

Both museums gave an extraordinary overview of different historical aspects of the town Lübeck, but I missed the connection between the two a bit. In the Lübeck 1500-exhibition, only little was said about Lübeck as a hanseatic trade centre, the very reason for it´s being also a centre for the arts, while in my opinion the Hansemuseum focused too much on the written sources. Therefore, in the following days in Hamburg, we discussed intensively questions of interdisciplinary research, its flaws and advantages, and the role of (art historical) museums today. These discussions were very interesting, also in light of our current project, and were for me the main added value of my participation in this course.

Posted in: Reports

When sailing North, beware of swimming cows and Hamburgers. The Carta Marina and the North Atlantic

Bart Holterman, 5 October 2015

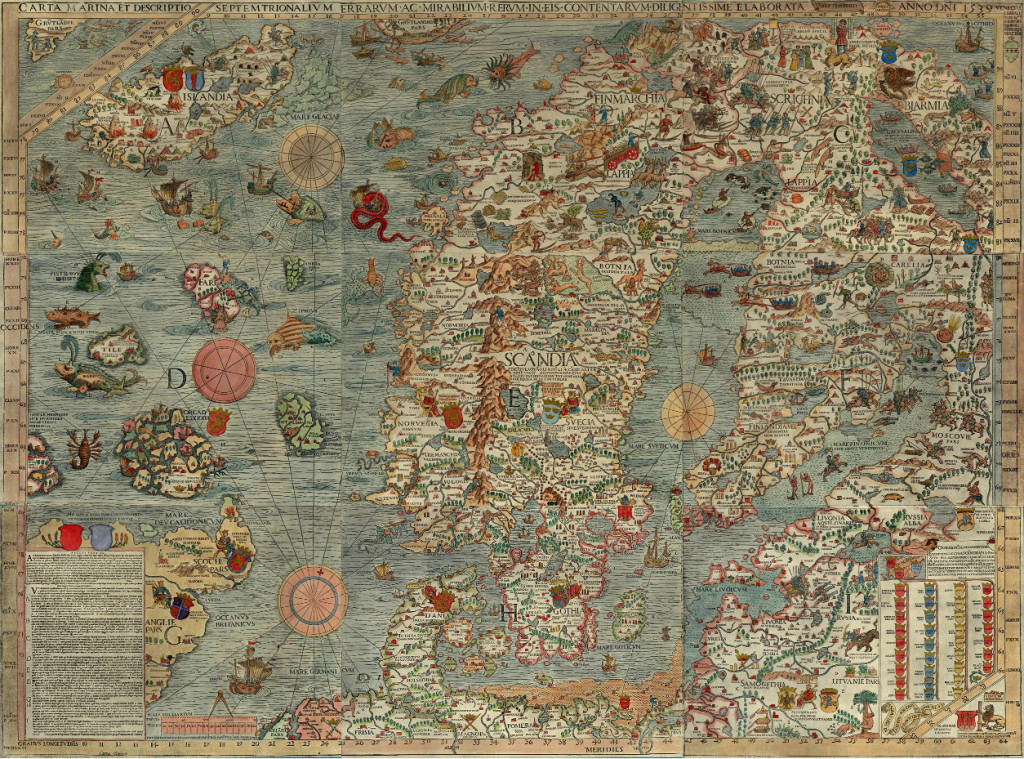

For the banner of this blog and our facebook page, we have displayed a section of the famous Carta Marina from 1539. On a first glance of the map, the many marvellous creatures that inhabit the land and the sea immediately catch the eye of the beholder, yet it also provides us with a good overview of the contemporary North Atlantic trade. Time to explore this remarkable document a bit further.

The map was made by Olaus Magnus (1490-1557), the brother of the last catholic bishop of Sweden. He had travelled Scandinavia and the lands around the Baltic Sea extensively before he was sent on a diplomatic mission to Rome by the Swedish king Gustav Vasa. He was never to return home. Dissatisfied by the Reformation in his homeland, Magnus stayed abroad, first in Lübeck and Danzig, later for a long time in Italy, soon joined by his expelled brother Johannes Magnus. In Italy he kept close contacts to learned men of his age, among others cartographers and travellers.

Under influence from these social circles, Magnus decided to transform his own knowledge about Northern Europe onto a map, which would appear in print in Venice in 1539. It was the first large-scale map of Scandinavia to be ever made, and had much influence on European cartography for the next decades. However, because of its high costs, the number of copies remained low. The map itself disappeared off the map of European learning, and was deemed to be lost since the late sixteenth century. Luckily in 1886 an intact copy of the map was discovered in the Bavarian State Library in Munich, and in 1961 another one, which now resides in Uppsala.

An explanation of the map appeared only in 1555 as Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus. In this book, Olaus Magnus described the geography, wildlife, and customs of the people of the North, illustrated with woodcuts. These woodcuts are clearly based on parts of the map, which includes many details about the people of the North, the political situation of the time, and the nature and wildlife. We can see kings sitting on their thrones, armies crossing the frozen Baltic Sea, people hunting seals, the most important towns and cities, lighthouses, whales attacking ships, enormous snakes, swimming cows and other sea monsters.

The map is divided into nine parts, marked A-I. It covers the entire Scandinavian peninsula, the Baltic, Northern Germany and the Netherlands, the entire North Sea and North Atlantic, including the coastline of Britain, the southern tip of Greenland and the mythical island Thule, known from classical geographical works. Of our interest are mainly the sections A and D, covering a large part of the North Atlantic.

Olaus Magnus probably never visited the North Atlantic himself. Instead, he had to rely on the stories and descriptions of others, for example the Northern German traders that told him about Iceland, the Shetlands and the Faroe Islands. Of the Shetlands and Faroes, Magnus must have had few information, as these archipelagos are only schematically drawn. One remarkable detail can be found on the Faroes, though, where we can see a whale being slaughtered on the shore, reminiscing a practice of hunting whales by driving them up the shore which is still practiced today.

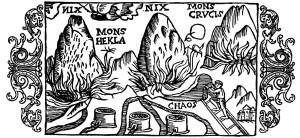

For Iceland, Magnus was clearly better informed. The Carta Marina was the first map that drew the island in its more or less actual shape. Moreover, three vulcanoes attest to Magnus’s knowledge of the high vulcanic activity on the island. The two episcopal sees, Hólar (Holensis) and Skálholt (Scalholdin), are displayed, as well as the monastery Helgafell (Abbatia Helgfiall), which was famed for its butter production (butirum). The three knights on the eastern part of Iceland should probably be seen as an indication of Danish military presence on the island.

Three volcanoes on Iceland, from Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (1555), photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Better than the natural, religious, and political situation, the map attests of the economic situation. Firstly, the main export goods of Iceland are indicated. These are, besides the already mentioned butter: stockfish, sulphur, and falcons. Stockfish was dried cod, highly valued in Europe as a preservable source of protein, and the main trade good of the arctic region. It is shown on a pile on the south coast. Just north of it, three containers of sulphur are depicted. Iceland was one of the few places where pure sulphur could be found. Sulphur, being among others a key ingredient for making gunpowder, was a highly valued substance. Finally, a gyr falcon (falco albus) can be seen on one of the northern peninsulas of Iceland. Gyr falcons are only found in arctic regions, and due to its being the largest and strongest species of falcon, it was highly valued by the nobility for use in falconry.

Apart from the export goods, the realities of the north atlantic trade are displayed in considerable detail on the map. Various trading harbours are indicated, most notably Hafnarfjörður (Hanafiord), where merchants from Hamburg had built a church. We can see ships lying at anchor at these harbours, and three tents at Ostrabord, which probably indicate the temporary booths the merchants set up on the shore and where they displayed their goods on sale during the summer.

The most important countries and cities trading with the island are also indicated. We can see a ship from Bremen at anchor near Ostrabord, an English ship which confused a whale for an island, a ship from Lübeck being attacked by whales, and a Scottish ship under attack by one from Hamburg, indicating the dominance of Hamburg in the North Atlantic trade. It was no exception that competition between merchants from different places led to violent clashes, as in 1523, when the crews of ships from Bremen and Hamburg attacked an English ship in a conflict over the rightful ownership of an amount of stockfish, resulting in casualties among the English.

These elements make the Carta Marina a wonderful visual testimony of the North Atlantic trade in the sixteenth century.

Posted in: Sources