Presentations about Hanseatic North Atlantic trade at Low German Science Slam

Hans Christian Küchelmann, 31 July 2023

Within this years Low German Language Festival “Platt Land Fluss” (Flat Land River) the Institut für Niederdeutsche Sprache (INS, Institute for Low German Language) organises a Low German Science Slam entitled “Höör to – fraag na – weet Bescheed!” (Listen – ask – know) on the 16th of September in Bremen.

Two lectures will present outputs of our research into Hanseatic North Atlantic trade respectively the projects “Between the North Sea and the Norwegian Sea” and “Looking in from the Edge” (LIFTE):

Mike Belasus

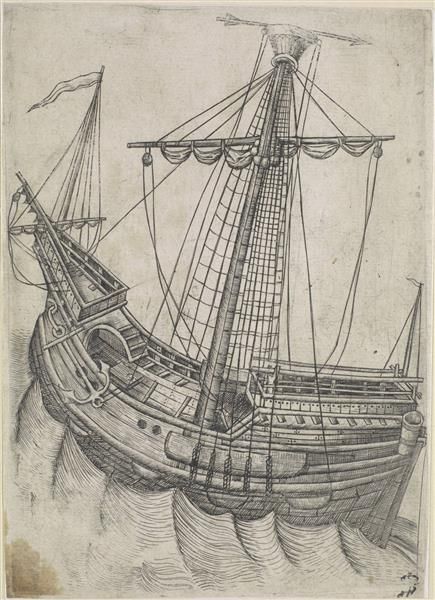

Was macht die Kuh auf dem Schiff!? Wie uns eine Auseinandersetzung mit Todesfolge vor 466 Jahren Details über die Konstruktion alter Bremer Handelsschiffe verrät

[What does the Cow on the Ship!? How a Quarrel with fatal Consequences 466 Years ago reveals Details about the Construction of ancient Bremen Merchant Ships]

Hans Christian Küchelmann

Der geheimnisvolle isländische Hase, der sich in einen Socken verwandelte

[The enigmatic Icelandic Hare, which turned into a Sock]

Event Details:

Science Slam

16. 9. 2023, 11:00-13:00

Institut für Niederdeutsche Sprache (INS)

Schnoor 41-43, 28195 Bremen

mail: ins@ins-bremen.de

tel: +49-421-324535

Festival program

Posted in: Announcements

Immer Weiter – Fragen und Antworten, Teil 2

Bart Holterman, 23 May 2023

(for English see below)

Hier beantworten wir die Fragen, die Besuchenden der Ausstellung „Immer Weiter – Die Hanse im Nordatlantik“ gestellt haben. In diesem zweiten Teil geht es um die Fahrt zwischen Norddeutschland und den Inseln und das Leben an Bord.

Wie lange war man damals von Bremen nach Shetland unterwegs?

Die Dauer der Fahrt zwischen Norddeutschland und Shetland war stark vom Wetter abhängig, vor allem von der Windrichtung und -stärke. Einige Tage bis einer Woche war man jedoch sicher unterwegs. Der Bremer Schiffer Brüning Rulves beschreibt zum Beispiel in seiner Memoiren eine Reise von Bremen nach Shetland im Jahr 1551, die vier Tage im Anspruch nahm.

Wie sicher waren die Schiffe im Vergleich zu heutigen Schiffen? Gab es ein Rettungskonzept?

Obwohl die meisten seefahrenden Schiffe sehr stabil gebaut waren, war die Seefahrt sehr viel gefährlicher als heutzutage. Dabei war es nicht sosehr der Bau des Schiffes, sondern die Elemente, die die größte Gefahr darstellten. Das Risiko in einem Sturm zu geraten und Schiffbruch zu erleiden war reell. In so einem Fall gab es kein Rettungskonzept, und konnte man nur hoffen, es zu überleben.

Haben sich die Leute an Bord mal geprügelt?

Das Zusammenleben vieler Leute auf engstem Raum während eines langen Zeitraums führte selbstverständlich zu Spannungen und nicht selten auch zu Prügeleien. Unter anderem aus diesem Grund herrschte an Bord eine strikte Hierarchie, wobei der Kapitän die oberste Befehlsgewalt hatte. Laut dem hansischen Seerecht war es ihm erlaubt, seine Besatzungsmitglieder (einmal) zu schlagen. Trotzdem liefen solche Situationen manchmal aus dem Ruder, wie zum Beispiel bei dem Tod des Bremer Schiffers Cordt Hemeling in Shetland im August 1557.

Was hat man damals an Bord von Schiffen gegessen und getrunken?

Auf längeren Reisen konnten natürlich keine leicht verderbliche Nahrungsmittel mitgenommen werden. Deswegen hat man vor allem getrocknete oder gesalzene Lebensmittel gegessen, wie Schiffszwieback und gesalzenes Fleisch. Auch Stockfisch und getrocknete Erbsen und Bohnen werden regelmäßig in Proviantlisten erwähnt. Getrunken hat man dabei hauptsächlich Bier. In Rechnungen für Seereisen wird regelmäßig einen Unterschied zwischen Schiffsbier gemacht: Bier das man an Bord getrunken hat bzw. das als Handelsware dienende Bier.

English version

Here we answer the questions which were asked by visitors of our exhibition „Immer Weiter – Looking In From The Edge“. This second part bundles the questions about the journey between Northern Germany and the islands and life on board.

How long did it take to travel from Bremen to Shetland in those days?

The duration of a ship’s journey depended for a large degree on the weather conditions, especially the wind direction and speed. A couple of days until a week was a likely duration for the journey from Northern Germany to Shetland. For example, the skipper Brüning Rulves from Bremen mentions in his memoirs a journey from Bremen to Shetland in 1551 which lasted four days.

How secure were historical ships in comparison to modern ships? Was there a rescue plan?

Although most seagoing ships had quite sturdy constructions, seafaring in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period was much more dangerous than nowadays. It was not so much the construction of the ship, but the elements which were dangerous. There was a high risk of getting caught up in a storm and to suffer shipwreck. In those cases there were no rescue concepts; one could only hope to survive it.

Did the people on board fight now and then?

The cohabitation of many people in a cramped space during a large period of time of course led to tensions, and not rarely to violence. Among others for this reason, a tight hierarchy prevailed on board, with the highest authority in the hands of the captain. According to Hanseatic maritime law, he was allowed to hit the others on board (once) as a disciplinary measure. However, this didn’t prevent the violence getting out of hand sometimes, such as in the case about the death of Bremen skipper Cordt Hemeling in Shetland in August 1557.

What did they eat and drink on the ships back in the day?

Perishable foodstuffs of course could not be taken on long journeys. For this reason the people on board mostly lived on dried and salted food, such as ship biscuits and salted meat. Dried peas and beans and stockfish are other examples of food which are regularly listed as provision on ship journeys. It was mainly washed down with beer. Accounts for fitting out merchant ships regularly make the distinction between ship beer and merchant beer, of which the former was drunk on board, whereas the latter served as merchandise.

Posted in: Exhibition, General

Immer Weiter – Fragen und Antworten, Teil 1

Bart Holterman, 19 April 2023

(for English see below)

Am 23. März wurde im Deutschen Schifffahrtsmuseum die Ausstellung “Immer Weiter – Die Hanse im Nordatlantik” eröffnet. Am Ende dieser Ausstellung können Besuchenden Fragen über die Themen der Ausstellung hinterlassen. Nach fast einem Monat sind wir sehr erfreut über die große Zahl der Fragen, die dort gestellt wurden! Nun ist es Zeit, auf einige davon zu antworten. In dieser Post haben wir Fragen gebündelt, die mit Kommunikation und Alltag auf den Inseln zu tun haben.

Welche Sprache haben die Händler benutzt?

Im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert sprach man in Norddeutschland noch meistens Niederdeutsch, eine Sprache die noch heute als Plattdeutsch bekannt ist. Seit der Hansezeit war diese Sprache in großen Teilen Nordeuropas die internationale Handelssprache, vergleichbar mit Englisch heutzutage. Vor allem im Dänischen und Norwegischen sind noch viele niederdeutsche Leihwörter anzutreffen. Es ist daher anzunehmen, dass die deutschen Kaufleute in Shetland auch Niederdeutsch gesprochen haben, und dass dies von ihren Handelspartnern auch durchweg verstanden wurde. So gibt es Dokumente, die belegen, dass Shetländer gefragt wurden, deutschsprachige Dokumente für die schottische Verwaltung ins Englische zu übersetzen.

Andererseits hatten die deutschen Kaufleute wahrscheinlich durch ihre jahrzehntelange Anwesenheit auf den Inseln auch einige Kenntnisse der Sprache der Inselbewohner. Diese sprachen noch bis ins 18. Jahrhundert eine skandinavische Sprache, Norn genannt. Die Obrigkeit benutzte jedoch zunehmend die schottische Version des Englischen. Aus Briefen Bremer Kaufleute des späten 17. Jahrhunderts wissen wir, dass die deutschen Kaufleute auch Schreibfähigkeiten in dieser Sprache besaßen.

Im Handelsalltag wurden all diese Sprachen wahrscheinlich neben- oder durcheinander benutzt, je nachdem, mit wem man handelte.

Wurde Wissen über Sprache und Gepflogenheiten nur innerhalb der Handelsfamilie weitergegeben, oder gab es auch Schule?

Es gab sicher auch Schulen im Spätmittelalter und in der Frühen Neuzeit. Allerdings waren diese meistens darauf gerichtet, die lateinische Sprache zu lehren und für ein wissenschaftliches Studium oder Verwaltungsfunktionen vorzubereiten. Praktisches Wissen über den Handel wurde erworben, indem man in der Lehre bei einem Kaufmann ging. Dies musste aber nicht zwingend ein Mitglied der eigenen Familie sein. Aus Island wissen wir, dass angehende Kaufleute zudem einen Winter lang bei einer isländischen Familie verblieben, um so die Sprache und Sitten der zukünftigen Handelspartner kennenzulernen und zudem erste Handelskontakte zu knüpfen. Ob dies in Shetland auch der Fall war ist nicht bekannt, aber es wäre anzunehmen.

Wie haben die Bremer damals auf Shetland gelebt?

Die deutschen Kaufleute in Shetland hatten keine festen Häuser, wo sie gewohnt haben. Die einzigen Gebäuden, die sie benutzten, waren kleine Buden, die als Lager- und Verkaufsräume dienten. Vielleicht haben die Schiffer und Kaufleute auch in diesen Buden übernachtet, aber die restlichen Besatzungsmitglieder und Gehilfen schliefen an Bord der Schiffe, die in den Buchten vor Anker lagen. Hier lebten sie dicht aufeinander ohne viel Privatsphäre und durften nur von Bord, wenn der Schiffer es erlaubte. Dies wissen wir aus Streitfällen, wie z. B. dem über den Tod des Bremer Schiffers Cordt Hemeling, der im Sommer 1557 nach einer Prügelei an Bord starb.

Die vielen weiteren Fragen sind nächstes Mal daran!

The exhibition “Immer Weiter – Looking in from the Edge” was opened in the German Maritime Museum on 23 March. At the end of the exhibition, visitors have the possibility to ask questions about the topics of the exhibition. After almost a month we can say that we are positively surprised by the large number of questions asked! Now it is time, to start answering some of them. In this post we have bundled those questions, that have to do with communication and life on the islands.

Which language did the merchants use?

In the 16th and 17th century people in Northern Germany largely spoke Low German, a language that is still known as “Plattdeutsch” today. Since the Hanseatic period, this language was the universal language of trade for a large part of northern Europe, comparably to English today. Especially in Danish and Norwegian we can still find many Low German loanwords. We can thus assume that the German merchants in Shetland also spoke Low German, and that this was understood by their trading partners. For example, there are documents that attest that Shetlanders were asked to translate German letters into English for the Scottish authorities.

On the other hand, German merchants probably acquired some knowledge of the language of the islanders due to their decades-long contacts. They spoke a kind of Scandinavian language known as Norn until the 18th century. However, the authorities and the landowners used Scots, a variety of English, more and more. We known from late 17th-century letters of merchants from Bremen, that they possessed writing proficiency in Scots as well.

In the trading practice, all languages were probably used next to each other, depending on who the trading partners were.

Was knowledge about the language and customs only passed on within a merchant family, or was there also a school?

There certainly existed schools in the late Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, but these were mostly focused on teaching the Latin language and to prepare for scholarly studies or administrative roles. Practical knowledge about trading practices were transferred by entering into an apprenticeship with a senior merchant. This did not necessarily have to be a member of the own family, however. From Iceland we also know that there existed the practice that aspiring merchants would stay one winter with an Icelandic family to learn the language and customs of their future trading partners, and to establish a first trading network. Whether this was also the case in Shetland is not known, but it is very well possible.

How did the merchants from Bremen live in Shetland in those times?

The German merchants in Shetland did not possess houses in which they lived. The only buildings used by them were small booths, which served as storage facilities and shops. It is possible that the skippers and merchants also spent the night in those booths, but all the other crew members and servants slept on board the ships, which were at anchor in the bays of the islands. Here they lived closely together without much personal space or comfort. Moreover, they were only allowed to leave the ship with explicit permission of the skipper. We know this from cases in which this led to problems, for example the case about the death of skipper Cordt Hemeling from Bremen, who died in Summer 1557 after a violent confrontation with his crew members on board.

The many other questions will be answered next time!

Posted in: Exhibition, General

German merchants at the trading station of Básendar, Iceland

Bart Holterman, 9 March 2018

The German merchants who sailed to Iceland in the 15th and 16th century used more than twenty different harbours. In this post we will focus on one of them: Básendar. The site is located on the western tip of the Reykjanes peninsula and was used as a trading destination first by English ships, then German merchants from Hamburg and later by merchants of the Danish trade monopoly. Básendar is mentioned in German written sources with different spellings as Botsand, Betsand, Bådsand, Bussand, or Boesand.

Aerial image of Básendar (marked with the red star), located on the Western end of Reykjanes peninsula, and Keflavík airport on the right (image Google Earth).

Básendar was one of the most important harbours for the winter fishing around Reykjanes. In the list of ten harbours offered to Hamburg in 1565, it is the second largest harbour, which annually required 30 last flour, half the amount of Hafnarfjörður (the centre of German trade in Iceland). German merchants must have realised it´s potential at a very early stage, and it is therefore the first harbour which we know to have been used by the Germans, namely by merchants from Hamburg, in 1423.

The trading station was located on a cliff just south of Stafnes, surrounded by sand. Básendar was always a difficult harbour, exposed to strong winds and with skerries at its entrance. Ships had to be moored to the rocks with iron rings. The topography of the site also made the buildings vulnerable to spring floods, and during a storm in 1799 all buildings were destroyed by waves, leading to the abandonment of the place. Today, the ruins of many buildings can still be seen, as well as one of the mooring rings, reminding the visitor of the site’s former importance.

Básendar also became a place for clashes between English and German traders. Already the first mention of Germans in the harbour came from a complaint by English merchants that they had been hindered in their business there. In 1477 merchants from Hull complained as well about hindrance by the Germans and in 1491 the English complained that two ships from Hull had been attacked by 220 men from two Hamburg ships anchoring in Básendar and Hafnarfjörður.

The famous violent events of 1532 between Germans and English started in Básendar as well, when Hamburg skipper Lutke Schmidt denied the English ship Anna of Harwich access to the harbour. Another arrival of an English ship a few days later made tensions erupt, resulting in a battle in which two Englishmen were killed. The events in 1532 marked the end of the English presence in Básendar, and we hear little about the harbour in the years afterwards. The trading place seems to have been steadily frequented by Hamburg ships, sometimes even two per year. In 1548, during the time when Iceland was leased to Copenhagen, Hamburg merchants refused to allow a Danish ship to enter the harbour, claiming that they had an ancient right to use it for themselves.

Hamburg merchants were continuously active in Básendar until the introduction of the Danish trade monopoly, except for the period 1565-1583, when the harbour was licensed to merchants from Copenhagen. From 1586 onwards, the licenses were given to Hamburg merchants again. These are the merchants who held licences for Básendar:

1565: Anders Godske, Knud Pedersen (Copenhagen)

1566: Marcus Hess (Copenhagen)

1569: Marcus Hess (Copenhagen)

1584: Peter Hutt, Claus Rademan, Heinrich Tomsen (Wilster)

1586: Georg Grove (Hamburg)

1590: Georg Schinckel (Hamburg)

1593: Reimer Ratkens (Hamburg)

1595: Reimer Ratkens (Hamburg)

The last evidence we have for German presence in Básendar provides interesting details about how trade in Iceland operated. In 1602 Danish merchants from Copenhagen concentrated their activity on Keflavík and Grindavík. A ship from Helsingør, led by Hamburg merchant Johan Holtgreve, with a crew largely consisting of Dutchmen, and helmsman Marten Horneman from Hamburg, tried to reach Skagaströnd (Spakonefeldtshovede) in Northern Iceland, but was unable to get there because of the great amount of sea ice due to the cold winter. Instead, they went to Básendar which was not in use at the time. However, the Copenhagen merchants protested. King Christian IV ordered Hamburg to confiscate the goods from the returned ship. In a surviving document the involved merchants and crew members told their side of the story. They stated that they had been welcomed by the inhabitants of the district of Básendar, who had troubles selling their fish because the catch had been bad last year and the fish were so small that the Danish merchants did not want to buy them. Furthermore, most of their horses had died during the winter so they could not transport the fish to Keflavík or Grindavík and the Danes did not come to them. The Danish merchants were indeed at first not eager to trade in Básendar, and did not sail there until they moved their business from Grindavík in 1640.

Further reading

Ragnheiður Traustadóttir, Fornleifaskráning á Miðnesheiði. Archaeological Survey of Miðnesheiði. Rannsóknaskýrslur 2000, The National Museum of Iceland.

Worth a fortune: Icelandic gyrfalcons

Natascha Mehler, 11 August 2016

Throughout the medieval and early modern period, Icelandic gyrfalcons were highly valued at the courts of European rulers and they were worth a fortune. Indeed, Frederick II (1194-1250), Holy Roman Emperor, already noted in his treatise De arte venandi cum avibus that the best falcons for use in falconry were gyrfalcons (…et isti sunt meliores omnibus aliis, Girofalco enim dicitur). The reason for this was that of all falcon species, gyrfalcons (Falco rusticolus) are the largest and most powerful. Their plumage varies greatly from completely white to very dark, of which the white variety was the most valued hawking bird in the Middle Ages, and still is today. They only inhabit sub-arctic and arctic areas, with their highest population density in Iceland (one pair per 150-300 km²). During the breeding season (roughly February to June) there are today 200-400 nesting pairs in Iceland, and in the winter the population increases to 1.000-2.5000 individuals, due to migrating birds from Greenland.

Written sources from the 16th century, when German merchants from Hamburg and Bremen dominated the trade with the North Atlantic islands, give us a better insight into the falcon business with Iceland. Matthias Hoep, a Hamburg merchant, has left behind a collection of account books (1582-1594) which show us that he traded in many commodities such as fish, timber, and tools, and specialized in the trade of falcons. Hoep employed falcon catchers to catch birds in Iceland for him and he made specific contracts with them. The books record a great number of falcons and other birds of prey that he bought from falcon catchers and which he then sold on. On 5 April 1584, Hoep made a contract with the falcon catchers and brothers Augustin and Marcus Mumme which he commissioned to travel to Iceland to catch falcons. The contract specified the bird species, the conditions of the birds upon delivery, and the prices Hoep was going to pay after the successful return of the Mummes from Iceland:

“On 5 April [1584] I have dealt in my house with Augustin and Marcus Mumme, in the name of god, that they shall sail to Iceland in the name of god, and we agreed that I will give for each pair of falcons 11 ½ daler, and 2 tercel [male falcons] for 1 falcon, and what is blank shall be counted as a red [unmoulted] falcon. But what is white and moulted once, or moulted twice and beautiful, for those I shall give them 20 daler for each falcon and 10 daler for a tercel. But what has moulted three times we shall agree upon with good will, and if god and luck provides them with white falcons, I will give the one who catches them black cloth for a jacket of 2 ½ ells, all of this is validated with a denarius dei of 1 sosling each, and both brothers have promised with an oath to bring the best birds they can get and to take no birds away, neither in Iceland nor during the journey back, until they have all been delivered to me.“

Roughly five months later, in September 1584, the brothers returned from Iceland and handed over 49 birds to Matthias Hoep.

Detail of the Carta Marina (1539) showing the coat of arms of Iceland (stockfish), with a gyrfalcon (FALCO ALBI) above.

Later documents tell us how the shipping of the falcons was done. During the 17th century, a Danish falcon ship went to Iceland annually to transport falcons from Iceland to Copenhagen. The falcons were kept below the deck and sat on poles which were lined with vaðmál. During the journey, the birds were fed with meat of cattle, sheep or birds, dipped in milk, and when they were sick, they were fed with a mix of eggs and (fish) oil. Upon arrival of the birds in Hamburg, Mathias Hoep checked their health and quality and he considered them in good state after they had eaten three times and their feathers were not broken.

Most of the birds that Hoep received were sold to English merchants such as John Mysken who bought 55 birds of prey in 1584 and had them shipped to England, most likely to be sold to the English court. It is likely that Hoep also had good contacts with Icelanders, both in Iceland and in Hamburg. His professional network may have included Magnús Jónsson (c. 1530-1591), who had studied law in Hamburg, probably until 1556. In Iceland he became chieftain and sýslumaður (sheriff) at Þingeyjaþingssýsla and Ísafjarðarsýsla, districts in the North of Iceland with a very high density of falcons. No wonder his seal from the year 1557 shows a gyrfalcon in the centre.

Seal of Magnús Jónsson, dated 1557. The priest Ólafur Halldórsson, a contemporary of Magnús Jónsson, described the seal in a poem: „Færði hann í feldi blá, fálkann hvíta skildi á, hver mann af því hugsa má, hans muni ekki ættin smá.” (transl. „he carried in a blue field, a white falcon on his shield, so that everybody shall think his family is not insignificant“).

In the second half of the 16th century, king Frederick II of Denmark-Norway (1559-1588) started to regulate the export of falcons to foreign countries. From the 1560s onwards, foreign falcon catchers needed to buy a permission (Icel. fálkabréf, falcon letter) to catch falcons.

Were falcons also caught in Shetland or the Faroes?

We have not found any written evidence for that. The obvious reason for this is that there are not many falcons around in Shetland and the Faroes. Gyrfalcons only appear as vagrant birds, and peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) exist in Shetland only in small numbers. However, it is worth pointing out that in the years 1601 to 1606 one Tonnies Mumme is recorded to have sailed each summer from Hamburg to Shetland. We do not know whether this is the same Tonnies Mumme that is reported as falcon catcher in Iceland in previous years, or whether Tonnies is related to the Augustin and Marcus Mumme mentioned above, but it seems very likely. He may have tried his luck in Shetland, or might have changed his profession and have traded in other items.

Further reading

Natascha Mehler, Hans Christian Küchelmann & Bart Holterman, The export of gyrfalcons from Iceland during the 16th century: a boundless business in a proto-globalized world. In: Gersmann, Karl-Heinz & Grimm, Oliver (eds.): Raptor and human – falconry and bird symbolism throughout the millennia on a global scale, vol. 3, Advanced studies on the archaeology and history of hunting 1 (Neumünster 2018), 995-1019.

Kurt Piper, Der Greifvogelhandel des Hamburger Kaufmanns Matthias Hoep (1582-1594). Jahrbuch des Deutschen Falkenordens (2001/2002), 205-212.

Björn Þórðarson, Íslenzkir fálkar. Safn til sögu Íslands og íslenskra bókmennta (Reykjavík 1957).

Posted in: Stories