German merchants at the trading station of Básendar, Iceland

Bart Holterman, 9 March 2018

The German merchants who sailed to Iceland in the 15th and 16th century used more than twenty different harbours. In this post we will focus on one of them: Básendar. The site is located on the western tip of the Reykjanes peninsula and was used as a trading destination first by English ships, then German merchants from Hamburg and later by merchants of the Danish trade monopoly. Básendar is mentioned in German written sources with different spellings as Botsand, Betsand, Bådsand, Bussand, or Boesand.

Aerial image of Básendar (marked with the red star), located on the Western end of Reykjanes peninsula, and Keflavík airport on the right (image Google Earth).

Básendar was one of the most important harbours for the winter fishing around Reykjanes. In the list of ten harbours offered to Hamburg in 1565, it is the second largest harbour, which annually required 30 last flour, half the amount of Hafnarfjörður (the centre of German trade in Iceland). German merchants must have realised it´s potential at a very early stage, and it is therefore the first harbour which we know to have been used by the Germans, namely by merchants from Hamburg, in 1423.

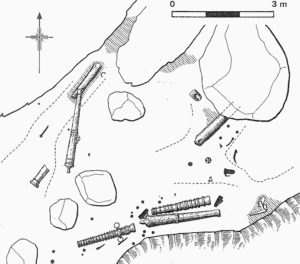

The trading station was located on a cliff just south of Stafnes, surrounded by sand. Básendar was always a difficult harbour, exposed to strong winds and with skerries at its entrance. Ships had to be moored to the rocks with iron rings. The topography of the site also made the buildings vulnerable to spring floods, and during a storm in 1799 all buildings were destroyed by waves, leading to the abandonment of the place. Today, the ruins of many buildings can still be seen, as well as one of the mooring rings, reminding the visitor of the site’s former importance.

Básendar also became a place for clashes between English and German traders. Already the first mention of Germans in the harbour came from a complaint by English merchants that they had been hindered in their business there. In 1477 merchants from Hull complained as well about hindrance by the Germans and in 1491 the English complained that two ships from Hull had been attacked by 220 men from two Hamburg ships anchoring in Básendar and Hafnarfjörður.

The famous violent events of 1532 between Germans and English started in Básendar as well, when Hamburg skipper Lutke Schmidt denied the English ship Anna of Harwich access to the harbour. Another arrival of an English ship a few days later made tensions erupt, resulting in a battle in which two Englishmen were killed. The events in 1532 marked the end of the English presence in Básendar, and we hear little about the harbour in the years afterwards. The trading place seems to have been steadily frequented by Hamburg ships, sometimes even two per year. In 1548, during the time when Iceland was leased to Copenhagen, Hamburg merchants refused to allow a Danish ship to enter the harbour, claiming that they had an ancient right to use it for themselves.

Hamburg merchants were continuously active in Básendar until the introduction of the Danish trade monopoly, except for the period 1565-1583, when the harbour was licensed to merchants from Copenhagen. From 1586 onwards, the licenses were given to Hamburg merchants again. These are the merchants who held licences for Básendar:

1565: Anders Godske, Knud Pedersen (Copenhagen)

1566: Marcus Hess (Copenhagen)

1569: Marcus Hess (Copenhagen)

1584: Peter Hutt, Claus Rademan, Heinrich Tomsen (Wilster)

1586: Georg Grove (Hamburg)

1590: Georg Schinckel (Hamburg)

1593: Reimer Ratkens (Hamburg)

1595: Reimer Ratkens (Hamburg)

The last evidence we have for German presence in Básendar provides interesting details about how trade in Iceland operated. In 1602 Danish merchants from Copenhagen concentrated their activity on Keflavík and Grindavík. A ship from Helsingør, led by Hamburg merchant Johan Holtgreve, with a crew largely consisting of Dutchmen, and helmsman Marten Horneman from Hamburg, tried to reach Skagaströnd (Spakonefeldtshovede) in Northern Iceland, but was unable to get there because of the great amount of sea ice due to the cold winter. Instead, they went to Básendar which was not in use at the time. However, the Copenhagen merchants protested. King Christian IV ordered Hamburg to confiscate the goods from the returned ship. In a surviving document the involved merchants and crew members told their side of the story. They stated that they had been welcomed by the inhabitants of the district of Básendar, who had troubles selling their fish because the catch had been bad last year and the fish were so small that the Danish merchants did not want to buy them. Furthermore, most of their horses had died during the winter so they could not transport the fish to Keflavík or Grindavík and the Danes did not come to them. The Danish merchants were indeed at first not eager to trade in Básendar, and did not sail there until they moved their business from Grindavík in 1640.

Further reading

Ragnheiður Traustadóttir, Fornleifaskráning á Miðnesheiði. Archaeological Survey of Miðnesheiði. Rannsóknaskýrslur 2000, The National Museum of Iceland.

Where have all the ships gone? The absence of German shipwrecks in Iceland

Bart Holterman, 22 December 2017

Mike Belasus, with Kevin Martin and Bart Holterman

Detail from Olaus Magnus Carta Marina 1539: The ship-destroying sea monster is symbolising the perils of a journey across the open ocean.

A Project on the Low German merchants’ trade from Bremen and Hamburg with the North Atlantic islands is not complete without the vessels that made trade across the ocean possible. The written sources tell us that many German ships were lost along the coast of Iceland, but until today, not a single mentioned shipwreck was found. This is not surprising, given the circumstance that underwater archaeology in Iceland is not even twenty years old.

Some facts about finding shipwrecks

The saying “Searching for a needle in a haystack” is fitting pretty well to the search for shipwrecks mentioned in historical documents, considering the abilities to determine a ship’s position in the past and the fact that 71 % of Earth’s surface is covered by water. Even today, many ships vanish without a trace. On top of that, the number of archaeologists looking for certain shipwrecks is extremely low. Therefore, most shipwrecks are found by accident and they remain more or less anonymous.

However, technology has improved and the potential for finding shipwrecks is much higher today than in the past. A number of devices can be used and combined for surveying the sea floor. A common combination is a side-scan sonar and a number of magnetometers, but this is still no guarantee for finding wrecks. When a ship is too decayed, or has settled into the sediment, the sound-rays of the side-scan sonar will not be able to produce a recognisable image. Moreover, magnetometers will not detect anomalies from the earth’s magnetic field when there is not enough metal on board the ship. Especially for medieval ships and early modern merchant vessels without guns, this can easily be the case. A sediment sonar could be a solution, which measures changes of density in the sediment with sound signals. The disadvantage is that waterlogged wood has the same density as waterlogged sediment. If a shipwreck has no denser cargo or ballast on board, the sonar will not detect density changes. Therefore such ships will remain hidden, even if an area is surveyed. Divers might be suggested as a final solution but a diver’s operating range is very limited, as he/she depends on depth, weather conditions, visibility and air supply.

The fact is that archaeologists rely in most cases on coincidences, which is how most of the known shipwrecks were found. The reason for this is that many other professions like builders, fishermen, geologists etc. spend much more time working on the sea floor than archaeologists, and sometimes stumble upon a wreck. One famous example for this is for example the “Bremen Cog” in the German Maritime Museum in Bremerhaven. A suction-excavator operator found it in the river Weser close to Bremen, when he was working on an extension of the riverbed. It became one of the most important finds in ship archaeology. Over the past decades, since underwater became an area of archaeological interest, hundreds of shipwrecks have been registered by the heritage departments of the German federal states but only a few of them could be identified by historical documents.

The author examining an anchor off the west coast of Gotland, at the site of the Visby-Disaster of 1566 (Photo: Jens Auer).

When we approach the shipwrecks from the historical documents, we have to realize that mentioned positions for lost ships are most of the time very vague. This situation can extend the search area dramatically without even knowing if the wrecks still exist as a coherent site. The conditions of the natural environment are vital to the survival of remains. Rugged coastlines, strong currents, micro-organisms, the chemical consistence of the water and the like can severely contribute to the decay of organic matter, metals and even certain types of stone. In the Mediterranean Sea, for example, ship hulls will not survive for a long time above the sea floor due to temperature, salinity and micro-organisms. Iron will soon vanish by the reaction with salt and oxygen and even marble and copper-alloys will decay. The opposite situation can be found in the Northern Baltic or the Sea Black Sea, for example. The Northern Baltic is deep, has a very low salt content and is cold. This prevents wood-decaying organisms to multiply and destruction from anchors or looting divers. The Black Sea water, on the other hand, has hardly any oxygen in a certain depth, which almost freezes time on the sea floor.

In addition, the circumstances of the sinking in connection to the natural environment play an important role. A German ship in Spanish service in 1588, the Gran Grifon, hardly left any structural remains. Another extreme example is the destruction of a united navy fleet of Lübeck and Danish ships during the Nordic Seven Years War on the west coast of Gotland in 1566. Out of thirty-seven ships, fifteen were lost and 6000 to 8000 sailors lost their lives in the so-called Visby-Disaster. Intensive archaeological diving surveys for several years could not reveal any wreck site. The ships literally vanished, most likely because they disintegrated in the storm on the rough sea floor and their remains were thrown up on the beach.

These examples shows us that a sunken ship mentioned in the historical documents does not always leave a proper wreck site. Sometimes scattered debris spread over square kilometres of sea floor can be all that is left of a ship.

The missing wrecks of Iceland

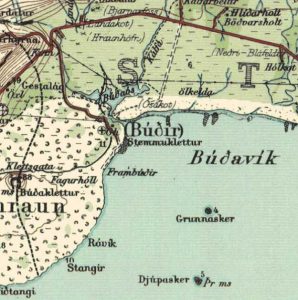

The site of the Bremen trading harbour Búðir/Bodenstede on the west coast of Iceland. It continued to be used by the Danes after 1601.

In theory, Iceland has a high potential for finding shipwrecks. Since the late 9th century, humans settle here and they had no other way than to cross the rough North Atlantic Ocean and make landfall on a rugged coast. Many ships, Norwegian, Danish, English, Low German and Dutch, evidently got lost on their route between continental Europe and Iceland. A considerable number of these found their end on the coast of Iceland, as we can read in the historical documents. Ragnar Edvardson has calculated a number of about 450 shipwrecks in Iceland, from the period from 1100 to 1900, most of which foundered on the West coast. Until today, no wreck from the period of the Low German trade has been found. The oldest ship found in Iceland is currently a Dutch merchantman, which sank in the harbour at Flatey in Breiðafjörður in 1659, and is currently under investigation by Kevin Martin. The scarcity of known shipwrecks in Iceland is not necessarily because they vanished completely, but because maritime archaeology is a very young discipline in this country and started only with sporadic projects from 1993 onwards. The relatively few inhabitants of Iceland also reduce the possibility of coincidental discoveries of wrecks due to the lack of building activities.

Vive la Coïncidence!

However, coincidences happen – even in Iceland. In 1998, an excavator hit timbers while digging a cable trench near Búðir on the Snæfellsnes peninsula in Western Iceland. They turned out to be fragments of a ship that was buried under the sand of an estuary. Some timbers and ballast stones were recovered by archaeologist Björn Stefánsson, and brought to the National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavik, were they were documented and put in storage. None of the recovered timbers was suitable for dendrochronological dating, but the ballast included stones that can possibly originate in Norway, Britain or Greenland. However, this does not give any indication were the ship was coming from, because ballast was taken from board and loaded in all harbours depending on the cargo and to adjust the angle of the ship in the water, to trim the ship. The recovered timbers give the impression of an old carvel-built ship. The material seems not to be of the finest quality, but this is hard to judge from only a handful of timbers. A promising fact is that Búðir was an important trading centre in Iceland for at least 200 years. It was already visited by Bremen merchants in the late 16th century, who called it “Bodenstede”. For a long time it was the main trading site for the Snæfellsness Peninsula, called first by cargo ships of the Low German merchants and later by Danish and Dutch ships. It was abandoned as a trading post in 1787.

The recovered ship timbers from Búðir today at the National Museum of Iceland, Reykjavik (Photo: Kevin Martin)

For this reason, we have written sources on the activities on this site including the loss of several ships during these 200 years. The problem for the identification of the accidental found ship is the fact that there was not only one ship lost near the site. We know at least about eleven ships that are reported to have been lost at Búðir and its harbour Búðavik. Of those eleven ships, one was from Bremen. It belonged to the merchant Vasmer Bake and sank in or close to the harbour of Bodenstede in 1587. This was reported by Carsten Bake, his son, who himself was involved in the Iceland trade. In 1607, a Danish ship wrecked at Búðir. For 1666, another ship sank west of Búðir. More ships sank in this area in 1724, 1728 (Danish) and 1754, and lastly, Bjarni Sívertsen’s cutter, which got lost here in 1812.

Certainly, it is possible that the ship found in 1998 is Vasmer Bake’s lost vessel from 1587, but the timbers cannot give us any more detailed information. All we can say today about the few recovered timbers is that there are five floor timbers and two fragments with an unknown function. The floor timbers indicate that the cable trench hit the wreck most likely in the bow section, leaving most of the buried remains uncovered. Each plank was attached to each frame with at least two tree nails, and each frame was connected to the keel with one or two tree nails. The dimensions of the floor timbers vary a lot, from flat and wide to high and narrow. This might be an indication that whoever built the ship faced either a shortage of crooked compass timbers, or the building did not rely on an even framing in a shell based building method, or both. However, it can also not be excluded that we face the remains of Bjarni Sívertsen’s cutter from 1812. Only future investigations might give us an answer.

References:

Edvardson R. and Grassel Ph., The Potential of Underwater Archaeology in the North Atlantic. In: N. Mehler, Travelling to Shetland, Faroe and Iceland during the 15th to 17th centuries (in press).

Stefànson, B., Skipsviðir úr Búðaósi. Rannsóknaskýrslur fornleifadeildar 1998. Fornleifadeild þjóðminjasafns Íslands, Reykjavik 1998

Posted in: General, Reports, Stories

El Gran Grífon – The story of a Hanseatic ship in the Spanish Armada, wrecked in Shetland

Philipp Grassel, 29 June 2017

In the 15th to 17th centuries, the North Atlantic Islands of Shetland, Faroe and Iceland were frequently visited by Hanseatic merchants, who usually made one voyage each year. The trading season started roughly in April and finished in August/September and because of its regular character, we have much information about the number of Hanseatic ships sailing North each year.

Map of the Shetland Islands with the positions of Hanseatic ship losses. Fair Isle and the wreck of the Gran Grífon can be seen in the smaller map (map created by P. Grassel)

In the middle of the 16th century, on average 5 ships per year from Bremen and 1 or 2 ships from Hamburg travelled to Shetland. Contemporary sources from 1560 speak of a minimum of 7 ships from Bremen and Hamburg in Shetland harbours. In Iceland, the numbers were even higher. For example in 1585, 14 ships from Hamburg alone and 8 ships from Bremen, Lübeck and Danzig reached Icelandic harbours, and in 1591 as many as 21 ships from Hamburg arrived in Iceland. In spite of these high numbers of voyages and some documented losses of Hanseatic ships – there are at least 10 known losses around Shetland and 3 losses around Iceland – no wrecks or remains of Hanseatic trading ships in the North Atlantic were found yet.

However, this does not mean that there are no Hanseatic trading vessels to be found in the North Atlantic at all. The only wreck which could be considered as Hanseatic are the remains of the El Gran Grífon (The great Griffin). This ship, which is the oldest known wreck both in Shetland and of all the North Atlantic islands, has a quite unusual history.

As the name already suggests, the Gran Grífon did not end up in Shetland by merchants from Bremen or Hamburg. Instead it was part of the famous Spanish Armada. This was a Spanish fleet which was sent in 1588 by the Spanish King Philipp II to invade England. The operation was a complete failure; the bulk of the fleet was lost after attacks by the English Navy and subsequent bad weather conditions on the North Sea.

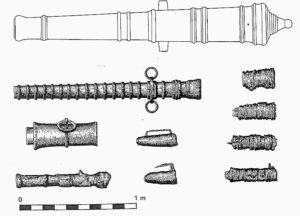

The Gran Grífon itself was a former Hanseatic merchant vessel from Rostock, a Hansa Town in the Baltic Sea, and was bought by the Spanish Navy for the Armada. This was not unusual; merchant ships were in this time often converted for military use in times of war. After the ship had been roughly modified, it was used as the flagship for a squadron of 23 supply and troop ships. These poorly armed squadrons, called urca squadrons, consisted of acquired merchant vessels and were commanded by Juan Gomez de Medina. The ship had a tonnage of 650 tons, a length of around 30 m and an armament of 38 unspecified cannons. The original crew of 43 men were supplemented with around 200 soldiers. So all in all carried the ship over 243 men.

After some battles with the English Navy, which took the lives of over 40 soldiers and seamen, the ship was driven to the North of the British Isles. It was accompanied by other Armada vessels like the Barca de Amburgo (probably another converted Hanseatic ship from Hamburg), Castillo Negro and La Trinidad Valencera. After the Barca de Amburgo sank, the Gran Grífon and the Trinidad Valencera took over the surviving men.

Shortly afterwards the contact between the ships was lost and the Gran Grífon sailed in a South-West direction, trying to get back to Spain through the Atlantic. However, after the ship reached the latitude of the Galway Bay in Western Ireland, a strong gale from the South-West got up and flouted the Ship back North. Since the ship was heavily damaged, Juan Gomez de Medina decided to search for the nearest possible land. This turned out to be Fair Isle, the most southern and remote island of the Shetland archipelago. The ship tried to anchor in vain before it was driven ashore and ended up on a cliff at Stroms Hellier at the Southeastern end of the island in September 1588. Most of the remaining crew members and soldiers, including Gomez de Medina, managed to escape from the ship before it disappeared in the waves.

For a long time, the wreck remained untouched in the 9-18m deep water. In 1728, W. Irvine salvaged three cannons from the wreck. An archaeological excavation was carried out between 1970 and 1977 by the Institute of Maritime Archaeology of St Andrews University, led by C. Martin. Unfortunately the wreck was barely preserved. Parts of the stern, a rudder pintle, cannons of different sizes, coins, cannon balls, musket bullets and lead ingots were found, recorded and removed. Other, smaller finds like the handle of a pewter or “Hanseatic” flagon, as well as a curved iron blade, were also recovered. The wooden part of the stern was preserved under a boulder, which had tumbled down from the nearby cliff. Most of the finds were brought to Lerwick, where they can be partly seen at the Shetland Museum.

Further reading:

K. Friedland, Der hansische Shetlandhandel, in: K. Friedland, Stadt und Land in der Geschichte des Ostseeraums (Lübeck 1973) 66-79.

C. Martin, Cave of the Tide Race – El Gran Grifon, 1588, in: C. Martin, Scotland’s Historic Shipwrecks (London 1998) 28-45.

P. Grassel, Late Hanseatic seafaring from Hamburg and Bremen to the North Atlantic Islands. With a marine archaeological excursus in the Shetland Islands, Skyllis. Zeitschrift für marine und limnische Archäologie und Kulturgeschichte, 15.2, 2015, 172-182.