Keeping the Faroese bishop warm – how a tiled stove tells the story of the Reformation in the Faroes

Natascha Mehler, 16 August 2017

with Torbjörn Brorsson, Martina Wegner and Símun V. Arge

In 1557 the Reformation in the Faroes came to an end when the Faroese bishopric at Kirkjubøur was abolished and its properties confiscated by Christian III of Denmark. This was the result of a process which started in 1539 when Amund Olafson, the last Catholic bishop, was replaced by Jens Gregersen Riber, the first Lutheran bishop of the Faroes. Jens Riber stayed at Kirkjubøur until 1557 when he left to take on a new position in Stavanger. We know very little about the lives of these two bishops. However, during archaeological excavations conducted in 1955 at the site of the former episcopal residence, the remains of a tiled stove dating to the early and mid-16th century came to light which add knowledge about the daily life at Kirkjubøur.

The tile fragments were now, more than 60 years after their discovery, analyzed as part of this research project. Tiled stoves were a luxurious rarity in the North Atlantic islands. In Iceland, for example, 16th-century tiled stoves are only known from the two bishoprics at Skálholt and Hólar, the Danish residence at Bessastaðir and from the monastery at Viðey. The Kirkjubøur fragments are the only remains of a tiled stove in the Faroes. In Denmark or Northern Germany, however, tiled stoves were rather common in burgher households and those of the nobility.

19 stove tile fragments were found at Kirkjubøur, all made from red clays, moulded with relief decoration and applied with a white slip and green lead glaze. Varying fabric and decoration indicates that the tiles are the products from at least two different workshops. This means that either the tiles of the former stove were exchanged during its lifetime, or the stove was made from tiles from different workshops. The latter interpretation would be rather unusual in a continental context but all known early modern tiled stoves from Iceland were made of tiles from different workshops because access, import and maintenance were very difficult.

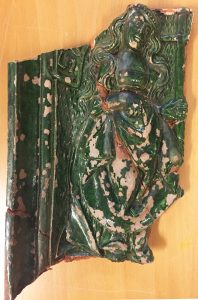

Stove tile made near Lübeck, with the remains of Judith and the head of Holofernes (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

The images on the Kirkjubøur tiles mirror the struggles of the introduction of the Reformation in the Faroes. All tiles show Christian or biblical motifs and themes, but while one of the identified motifs displays catholic imagery, others are clearly reformist in meaning. In many Northern European households such stove tiles decorated with Lutheran imagery were indeed used as a medium to express the Lutheran confession.

Stove tile produced in the area between Lübeck and Bremen, with the relief of probably a female Saint (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

One stove tile fragment shows a female figure with a cross in her left hand. A letter “S” is preserved, suggesting that this is a female saint such as Helena. If this interpretation holds true it would be a tile with purely Catholic imagery. The best preserved stove tile shows a bearded man in profile and the words [S]ANT PAVLO APOSTOLVS. Although this is a depiction of yet another saint – and thus rather Catholic in meaning – the letters of Paul the Apostle were often invoked by reformist theologians of Wittenberg. All other identified motifs were popular amongst supporters of Lutheranism. One fragment shows the lower body part of a female figure with a man’s head next to it. This is clearly a depiction of Judith with the head of Holofernes in her hand, a widespread stove tile motif in Lutheran contexts. And two identical tiles show the ascension of Jesus and parts of the creed of the Lutheran catechism. The surviving text reads 6 ER IST AVGEFARE[N] GEN HIMEL SITZET ZVR RECHTEN GOTES DES ALMECHTIGEN VATERS (transl. “he has ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of the Father”). The letter 6 indicates that this is the sixth stove tile in a series.

Eight fragments of these stove tiles were selected for analysis by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MA/ES), a standard method in ceramic analysis, carried out by Torbjörn Brorsson (Kontoret för Keramiska Studier). The main goal of the analysis was to determine the chemical composition of the various fabrics, with the aim to identify the workshops which produced these tiles. The results show that the tile with Paul the Apostle was made in Lübeck, and the tile with Judith and Holofernes, as well as the tile with the creed of the Lutheran catechism, in the surroundings of Lübeck. The tile with the female saint was made in the area between Lübeck and Bremen, which also includes Hamburg. This is no surprise; Northern German potters were the leading craftsmen to supply the Northern European market with stove tiles at that time.

The stove tiles were imported to the Faroes during the period when the Faroes were licensed to Hamburg citizen Thomas Koppen, between 1529 and 1553. Thomas Koppen was Oberalter of the churches in Hamburg and therefore an important figure in the process of the Reformation there. Maybe Koppen’s merchants (very likely he never visited the Faroe Islands himself) had brought the tiles from Lübeck via Hamburg to the Faroes. It is also very likely that Norwegian merchants from Bergen brought the tiles to the Faroes. The islands were closely connected to Bergen, with many ships travelling between the harbours of Tórshavn and Bergen. Lübeck merchants held a very important position in Bergen at that time and the tiles could have been brought from Lübeck first to Bergen and then went further to the Faroes.

The story that the tile finds suggest is such: a tiled stove was first erected at Kirkjubøur during the office of the Catholic bishop Amund Olafson, and fitted with tiles such as the one with the female saint. When Jens Riber took over as first Lutheran bishop in 1539 he bought new tiles from a different workshop and exchanged the purely Catholic images on his stove with motifs of the new faith. Only then could he enjoy the comforting warmth effusing from his stove without being agonized by the troubling sight of Catholic images.

References:

Julia Hallenkamp-Lumpe, Das Bekenntnis am Kachelofen? Überlegungen zu den sogenannten “Reformationskacheln”. In: C. Jäggi and J. Staecker (eds.), Archäologie der Reformation. Studien zu den Auswirkungen des Konfessionswechsels in der materiellen Kultur (Berlin 2007) 239–258.

Louis Zachariasen, Føroyar sum rættarsamfelag 1535–1655 (Tórshavn 1961), see pages 161–184.

What did the German trading stations in Iceland look like?

Natascha Mehler, 27 April 2017

The Danish trading station at Grundarfjörður, as depicted in the 1790s. Before the Danes took over the trading post in the early 17th century it was in the hands of German merchants.

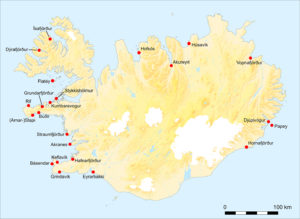

In the 16th century there were approximately 25 trading stations in Iceland which were regularly frequented by merchants from Bremen, Hamburg, Oldenburg or Lübeck. Most of these stations lay in the western part of the island, around the Snæfellsnes and Reykjanes peninsulas and in the Westfjords, because these were the areas where most fishing settlements were located and where cod, which was transformed into the main trading commodity stockfish, was abundant.

German trading stations in Iceland. Landey is near Kumbaravogur (map by Libby Mulqueeny, Mark Gardiner and Natascha Mehler).

It is difficult to tell what these German trading stations looked like because none have survived until today. In 1604, the Danish king Christian IV ordered to tear down all German buildings in Iceland, as a consequence of his imposition of the Danish trade monopoly (1602–1787). During the early 17th century many of the German trading stations (such as Grundarfjörður in the image above) were taken over by Danish traders and subsequently developed into permanent and more substantial settlements, many of which still exist today. What we don’t know is whether the Danish traders really tore down the German buildings, as was the will of the king, or simply re-used the buildings and infrastructure. The latter would certainly have been more practical in a country where building material was scarce.

Luckily, a handful of German trading sites did not develop into modern settlements and remains have survived until today. One of them is situated on the small tidal island of Landey at the northern side of the Snæfellsnes peninsula, near the present farm of Bjarnarhöfn. Written sources mention a trading post visited by merchants from Oldenburg and Bremen in the 1590s, but the amount of information from the surviving documents is very low. In 1593, Carsten Bake from Bremen acquired a three-years license for the harbour, and afterwards the harbour was given to the count of Oldenburg. In 1599, a request by the count to renew the license for Landey was denied by the Danish king because it was already in use by someone else. Who this person was is not mentioned.

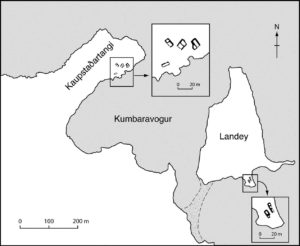

Ruins of German trading stations at Kaupstaðartangi and Landey (map by Mark Gardiner, Natascha Mehler and Libby Mulqueeny).

Today, Landey is a small island only used by sheep for grazing. The outlines of two buildings are clearly visible. They are situated on a small plain near a beach that was used as a landing site, to pull up small boats. The western side of the island faces a bay called Kumbaravogur, and on the other side of that bay lies Kaupstaðartangi, a headland where the remains of a trading station called Kummerwage have survived. This close proximity could be the reason why Landey started to be used as a trading post in the first place, as Kummerwage had been a harbour of Bremen merchants for a long time, but was given to Joachim Kolling from Oldenburg in 1580. Bremen tried hard to get the harbour back, but without success. The merchants of Bremen must have tricked the Danish king in requesting a license for the nearby Landey. When the king realised his mistake he included the clause that the license would go to Oldenburg after the Bremen one expired.

The ruins of two buildings at Landey (centre), on a green plain overlooking the landing site (image Natascha Mehler, 2016).

A trial excavation conducted with Fornleifastofnun Íslands at Landey in the summer of 2016 has shown that both buildings on Landey were indeed dwellings, although rather simple constructions. The walls were built in the Icelandic way, made of turf with stone linings. A fire place was discovered in the western building and no signs of furniture or other equipment were found. However, ten fragments of a ceramic cooking pot made of red earthenware were discovered. ICP-MS analysis of the sherds (conducted by Torbjörn Brorsson, KKS) has shown that the pot was made in Bremen, or in very close vicinity thereof (e.g. in Oldenburg).

The trial trench through the western building at Landey. The outlines of the building are clearly visible, as is the turf construction of the wall (image Vilmundur Pálmason, 2016).

The building to the east has two inner partition walls which indicates that it could have been used as a storage facility. Taking the scarce written and archaeological evidence together we can conclude that the buildings were indeed dwellings of some sort but only used for a very short time. This corresponds well with what we know about the Icelandic trading stations from other written sources: they were only used during the summers, when the foreign vessels were in Iceland, and their owners did not invest in solid infrastructure because they were not sure whether they would return the next summer. For Landey, records only exist for the 1590s.

Written sources indicate that merchants generally slept in the dwellings on land while the ship´s crew stayed on board. However, the excavations at Landey give food for thought. A Northern German merchant might have found it more comfortable to stay on board than to spend his nights in a damp and dark turf building…

References:

D. Kohl, Der oldenburg-isländische Handel im 16. Jahrhundert. Oldenburger Jahrbuch 13, 1905, 34–53.

Mehler & M. Gardiner, On the Verge of Colonialism: English and Hanseatic Trade in the North Atlantic Islands, in Peter Pope and Shannon Lewis-Simpson (eds.), Exploring Atlantic Transitions: Archaeologies of Permanence and Transience in New Found Lands. Society of Post-Medieval Archaeology Monograph 8 (Woodbrige 2013) 1-15.

Oldenburg, Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv, Best. 20, -25, no. 6.

Copenhagen, Rigsarkivet, Tyske Kancelli D 11, Pakke 28 (Island og Færøer, Supplement II, no. 25)

German-Icelandic trade relations: the case of Eiríkur Árnason

Bart Holterman, 30 March 2017

Trade in the North Atlantic was neither simply an exchange of goods between ports in Iceland and in Germany, nor did the islanders stay at home and wait for German merchants to show up each spring. In some cases, more complex relations between islanders and Germans existed, and in what follows we will present an example from Iceland to highlight the complexity of the trade relations between Icelanders and Germans. Germans were not allowed to settle in Iceland, but Icelanders were free to move or travel to Germany, which some did, and established networks of their own. Sometimes these links can be reconstructed in considerable detail with the help of both historical and archaeological sources. In this post, we will focus on one such case, that of Eiríkur Árnason Brandssonar (c. 1530-1586), sýslumaður (bailiff) of Múlaþing district in the East of Iceland.

Eiríkur Árnason was a powerful man in Iceland, who repeatedly got into trouble with Guðbrandur Þorláksson, bishop at Hólar. Eiríkur was appointed klausturhaldari, the keeper of the property of Skriðuklaustur monastery, located in the valley of lake Lagarfljót about 50km inland from the southeastern coast of Iceland. The monastery had been secularized in 1554, and the now royal property was administered by the klausturhaldari. Eiríkur, whose grandfather Brandur Hrafnsson had been the last prior of the monastery, held this office between 1564 and 1578.

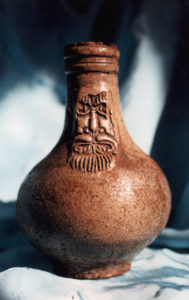

So called Bartman jug made of Rhenish stoneware, found in the house of the klausturhaldari of Skriðuklaustur (image Helgi Hallgrímsson).

In 1584, it seems that Eiríkur settled in Hamburg. He embarked on a voyage to Hamburg on the ship of Jochim Warneke and shortly afterwards married Anna Korfemaker and bought a brewery. The next year he travelled back and forth between Iceland and Hamburg and it is most likely that he was a member of the fraternity of St Anne that united most merchants and sailors who travelled to Iceland. In 1586 he died in Hamburg and was buried there at the cemetery of St Jakob.

There are numerous sources which shed a light on Eiríkur’s contacts with German merchants in Iceland. In the fjord now known as Berufjörður, south of Skriðuklaustur, Bremen merchants (who called the fjord Ostforde) had been trading for a long time. In 1575, a conflict broke out between two of them, Bernd Losekanne and Christoffer Meyger, due to alleged mutiny. In the ensuing court case before the Bremen city council, one of the problems discussed was the ownership of a barrel of osemund (iron from Sweden) which Losekanne had sold to Eiríkur Arnason but which was left in the merchant´s booth, of which Eiríkur as bailiff had the keys. Also, a load of vaðmál he left in the booth was destined for a Hamburg merchant named Matthies.

It is clear that during his time as sýslumaður and klausturhaldari, Eiríkur had been trading actively with the German merchants in the area. This is also attested by contemporary objects. From the house of the klausturhaldari stems a complete Bartman jug of the 16th century, a common pouring vessel of that time, produced in one of the major stoneware production centers along the Rhine (such as Frechen, Raeren or Cologne). It is more than likely that this jug was used by Eiríkur who had bought it from the German merchants in Berufjörður. Another link is the gravestone of his mother Úlfhildur Þorsteinsdóttir which is thought to have been imported from Germany by Eiríkur.

Eiríkur’s connections with German merchants probably went further than that. In 1580 Bernd Losekanne and Christoffer Meyger (who had apparently reconciled) complained about interference of Hamburg merchant Matthias Eggers in Ostforde. Eggers, on the other hand, said that he had a general trading license for Iceland which obviously permitted him to use any harbour he liked. Losekanne and Meyger then replied to this that this was unfair because Eiríkur had acquired that license for himself when he had visited the Danish royal court, and had entered into a trade agreement with the Hamburg merchants, in return for a part of their ship. Eggers was also probably the man named Matthies for which Eiríkur had put aside the vaðmál in 1575.

Merchants from Bremen are known to have entered into trade relations with Icelanders as well, but that might be a topic for a future post.

References:

Friederike Christiane Koch, Isländer in Hamburg 1520-1662. Beiträge zur Geschichte Hamburgs vol. 49 (Hamburg 1995) pp. 150-153.

Staatsarchiv Bremen, 2-R.11.ff.

Staatsarchiv Hamburg, 111-1, Cl. VII Lit. Kc. no. 11, Vol. 3.

Posted in: Stories

Uncovering the North Atlantic trade sherd by sherd

Natascha Mehler, 12 April 2016

When it comes to the goods transported by merchants from Bremen and Hamburg to the North Atlantic islands we have only limited sources at hand. The few extant account books list the commodities they sold to the inhabitants of the islands in return for stockfish, fish oil, sulphur or woolen cloth. But the written sources are not precise but rather general and never tell where the exported goods were manufactured. To complicate matters, (archaeological) material culture of the German period is scarce. Most of the goods traded by the Germans were bulk material such as grain or flour, cloth, timber, and beer, and to a lesser extent every day items that were hard to get on the islands: horse shoes, tools, knifes, wax etc. Many of these goods, especially those of organic material, have long been gone. Ceramics, however, are a different matter. Icelanders did not produce ceramic vessels (and the Faroese and Shetlanders only to a limited extent) which means that all pots, pans, jugs and beakers needed to be imported. A considerable amount of pottery from the 15th to 17th centuries has been found in Iceland, Shetland and Faroe but what can pottery sherds tell us about that trade?

Fragments of a so called “Schnelle”, a tankard produced in Siegburg in the 16th century, found at Tórshavn, the German trading station in the Faroe islands (photograph by Helgi Michelsen).

The sherds that have survived from excavations and in museum collections in Iceland show characteristic traits of wares common in Northern Europe. The ceramic assemblages of sites such as Gautavík (a German trading site in the East), Viðey (a monastery near Reykjavík), or Stóraborg (a farm at the South coast) consist of two distinctive ware groups: stonewares and redwares. Stoneware was used to produce drinking vessels such as jugs and beakers. They were widely traded over Northern Europe, via the river Rhine and ports of Northern Germany and the Netherlands. For the trained eye, these stonewares are relatively easy to determine. The majority stems from the famous medieval and early modern production centres along the Rhine such as Siegburg, Frechen, or Cologne; a second group can be traced back to Lower Saxony.

The origin of redwares, a general term for cooking vessels (pots, pans) and plates consisting of earthenware, is far more problematic to identify. Vessel shapes and fabrics of pottery workshops are generally very similar over a large area and it is therefore hard to determine where exactly a certain redware pot was produced. Distinguishing the redwares is mostly based on typological characteristics such as a distinctive form of the rim of a pot, but the Icelandic archaeological material is often too fragmented to allow an identification beyond doubts. However, provenancing these redwares would considerably change our understanding of the trade mechanisms and pottery consumption patterns in the North Atlantic.

Fragmented redware tripod with internal lead glaze found at the trading site of Gautavík, Iceland. It dates to the late 16th century but the place of origin remains enigmatic (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

Luckily, there are other methods than typology to identify the provenance of pottery. In recent years, ICP analysis (inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry), widely used in archaeological science, has proven to be a reliable method to determine the chemical fingerprint of the clays used for the production of ceramic vessels. ICP analysis has been applied successfully at a large number of redwares produced in Southern Scandinavia and Germany, with ground breaking work done by Torbjörn Brorsson (Kontoret för Keramiska Studier, Sweden) and Jette Linaa (Moesgaard Museum, Denmark). This means that we now have a solid base of reference material at hand which is necessary to securely identify the origin of the redwares in question. The application of the method in ceramic studies and an overview on the data reference material was presented in April 2016 at the inaugural meeting of the Baltic and North Atlantic Pottery Research Group (BNPG) which took place at the Historiska Museet Stockholm.

In summer 2016, redware fragments from selected sites in Iceland, Shetland and Faroe will be sampled in order to conduct ICP analysis. We will report on the results of the analysis, and what this means for the interpretation of the trading connections between Northern Germany and the North Atlantic islands.

Further reading:

Torbjörn Brorsson, A new method to determine the provenance of pottery – ICP analysis of pottery from Viking age settlements in Northern Europe. In: S. Kleingärtner, U. Müller, J. Scheschkewitz (eds.), Kulturwandel im Spannungsfeld von Tradition und Innovation. Festschrift for Michael Müller-Wille. Neumünster, 2013, 59-66.

Adolf Hofmeister, Das Schuldbuch eines Bremer Islandfahrers aus dem Jahre 1558. Bremisches Jahrbuch 80, 2001, 20-50.

Natascha Mehler, Die mittelalterliche Importkeramik Islands. Current Issues in Nordic Archaeology. Proceedings of the 21st Conference of Nordic Archaeologists, 6-9 September 2001, Akureyri, Iceland. Reykjavik 2004, 167-170.