German merchants at the trading station of Básendar, Iceland

Bart Holterman, 9 March 2018

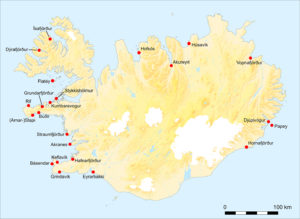

The German merchants who sailed to Iceland in the 15th and 16th century used more than twenty different harbours. In this post we will focus on one of them: Básendar. The site is located on the western tip of the Reykjanes peninsula and was used as a trading destination first by English ships, then German merchants from Hamburg and later by merchants of the Danish trade monopoly. Básendar is mentioned in German written sources with different spellings as Botsand, Betsand, Bådsand, Bussand, or Boesand.

Aerial image of Básendar (marked with the red star), located on the Western end of Reykjanes peninsula, and Keflavík airport on the right (image Google Earth).

Básendar was one of the most important harbours for the winter fishing around Reykjanes. In the list of ten harbours offered to Hamburg in 1565, it is the second largest harbour, which annually required 30 last flour, half the amount of Hafnarfjörður (the centre of German trade in Iceland). German merchants must have realised it´s potential at a very early stage, and it is therefore the first harbour which we know to have been used by the Germans, namely by merchants from Hamburg, in 1423.

The trading station was located on a cliff just south of Stafnes, surrounded by sand. Básendar was always a difficult harbour, exposed to strong winds and with skerries at its entrance. Ships had to be moored to the rocks with iron rings. The topography of the site also made the buildings vulnerable to spring floods, and during a storm in 1799 all buildings were destroyed by waves, leading to the abandonment of the place. Today, the ruins of many buildings can still be seen, as well as one of the mooring rings, reminding the visitor of the site’s former importance.

Básendar also became a place for clashes between English and German traders. Already the first mention of Germans in the harbour came from a complaint by English merchants that they had been hindered in their business there. In 1477 merchants from Hull complained as well about hindrance by the Germans and in 1491 the English complained that two ships from Hull had been attacked by 220 men from two Hamburg ships anchoring in Básendar and Hafnarfjörður.

The famous violent events of 1532 between Germans and English started in Básendar as well, when Hamburg skipper Lutke Schmidt denied the English ship Anna of Harwich access to the harbour. Another arrival of an English ship a few days later made tensions erupt, resulting in a battle in which two Englishmen were killed. The events in 1532 marked the end of the English presence in Básendar, and we hear little about the harbour in the years afterwards. The trading place seems to have been steadily frequented by Hamburg ships, sometimes even two per year. In 1548, during the time when Iceland was leased to Copenhagen, Hamburg merchants refused to allow a Danish ship to enter the harbour, claiming that they had an ancient right to use it for themselves.

Hamburg merchants were continuously active in Básendar until the introduction of the Danish trade monopoly, except for the period 1565-1583, when the harbour was licensed to merchants from Copenhagen. From 1586 onwards, the licenses were given to Hamburg merchants again. These are the merchants who held licences for Básendar:

1565: Anders Godske, Knud Pedersen (Copenhagen)

1566: Marcus Hess (Copenhagen)

1569: Marcus Hess (Copenhagen)

1584: Peter Hutt, Claus Rademan, Heinrich Tomsen (Wilster)

1586: Georg Grove (Hamburg)

1590: Georg Schinckel (Hamburg)

1593: Reimer Ratkens (Hamburg)

1595: Reimer Ratkens (Hamburg)

The last evidence we have for German presence in Básendar provides interesting details about how trade in Iceland operated. In 1602 Danish merchants from Copenhagen concentrated their activity on Keflavík and Grindavík. A ship from Helsingør, led by Hamburg merchant Johan Holtgreve, with a crew largely consisting of Dutchmen, and helmsman Marten Horneman from Hamburg, tried to reach Skagaströnd (Spakonefeldtshovede) in Northern Iceland, but was unable to get there because of the great amount of sea ice due to the cold winter. Instead, they went to Básendar which was not in use at the time. However, the Copenhagen merchants protested. King Christian IV ordered Hamburg to confiscate the goods from the returned ship. In a surviving document the involved merchants and crew members told their side of the story. They stated that they had been welcomed by the inhabitants of the district of Básendar, who had troubles selling their fish because the catch had been bad last year and the fish were so small that the Danish merchants did not want to buy them. Furthermore, most of their horses had died during the winter so they could not transport the fish to Keflavík or Grindavík and the Danes did not come to them. The Danish merchants were indeed at first not eager to trade in Básendar, and did not sail there until they moved their business from Grindavík in 1640.

Further reading

Ragnheiður Traustadóttir, Fornleifaskráning á Miðnesheiði. Archaeological Survey of Miðnesheiði. Rannsóknaskýrslur 2000, The National Museum of Iceland.

What did the German trading stations in Iceland look like?

Natascha Mehler, 27 April 2017

The Danish trading station at Grundarfjörður, as depicted in the 1790s. Before the Danes took over the trading post in the early 17th century it was in the hands of German merchants.

In the 16th century there were approximately 25 trading stations in Iceland which were regularly frequented by merchants from Bremen, Hamburg, Oldenburg or Lübeck. Most of these stations lay in the western part of the island, around the Snæfellsnes and Reykjanes peninsulas and in the Westfjords, because these were the areas where most fishing settlements were located and where cod, which was transformed into the main trading commodity stockfish, was abundant.

German trading stations in Iceland. Landey is near Kumbaravogur (map by Libby Mulqueeny, Mark Gardiner and Natascha Mehler).

It is difficult to tell what these German trading stations looked like because none have survived until today. In 1604, the Danish king Christian IV ordered to tear down all German buildings in Iceland, as a consequence of his imposition of the Danish trade monopoly (1602–1787). During the early 17th century many of the German trading stations (such as Grundarfjörður in the image above) were taken over by Danish traders and subsequently developed into permanent and more substantial settlements, many of which still exist today. What we don’t know is whether the Danish traders really tore down the German buildings, as was the will of the king, or simply re-used the buildings and infrastructure. The latter would certainly have been more practical in a country where building material was scarce.

Luckily, a handful of German trading sites did not develop into modern settlements and remains have survived until today. One of them is situated on the small tidal island of Landey at the northern side of the Snæfellsnes peninsula, near the present farm of Bjarnarhöfn. Written sources mention a trading post visited by merchants from Oldenburg and Bremen in the 1590s, but the amount of information from the surviving documents is very low. In 1593, Carsten Bake from Bremen acquired a three-years license for the harbour, and afterwards the harbour was given to the count of Oldenburg. In 1599, a request by the count to renew the license for Landey was denied by the Danish king because it was already in use by someone else. Who this person was is not mentioned.

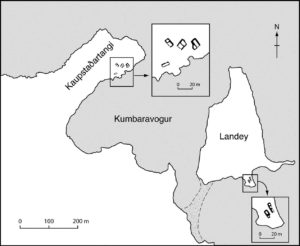

Ruins of German trading stations at Kaupstaðartangi and Landey (map by Mark Gardiner, Natascha Mehler and Libby Mulqueeny).

Today, Landey is a small island only used by sheep for grazing. The outlines of two buildings are clearly visible. They are situated on a small plain near a beach that was used as a landing site, to pull up small boats. The western side of the island faces a bay called Kumbaravogur, and on the other side of that bay lies Kaupstaðartangi, a headland where the remains of a trading station called Kummerwage have survived. This close proximity could be the reason why Landey started to be used as a trading post in the first place, as Kummerwage had been a harbour of Bremen merchants for a long time, but was given to Joachim Kolling from Oldenburg in 1580. Bremen tried hard to get the harbour back, but without success. The merchants of Bremen must have tricked the Danish king in requesting a license for the nearby Landey. When the king realised his mistake he included the clause that the license would go to Oldenburg after the Bremen one expired.

The ruins of two buildings at Landey (centre), on a green plain overlooking the landing site (image Natascha Mehler, 2016).

A trial excavation conducted with Fornleifastofnun Íslands at Landey in the summer of 2016 has shown that both buildings on Landey were indeed dwellings, although rather simple constructions. The walls were built in the Icelandic way, made of turf with stone linings. A fire place was discovered in the western building and no signs of furniture or other equipment were found. However, ten fragments of a ceramic cooking pot made of red earthenware were discovered. ICP-MS analysis of the sherds (conducted by Torbjörn Brorsson, KKS) has shown that the pot was made in Bremen, or in very close vicinity thereof (e.g. in Oldenburg).

The trial trench through the western building at Landey. The outlines of the building are clearly visible, as is the turf construction of the wall (image Vilmundur Pálmason, 2016).

The building to the east has two inner partition walls which indicates that it could have been used as a storage facility. Taking the scarce written and archaeological evidence together we can conclude that the buildings were indeed dwellings of some sort but only used for a very short time. This corresponds well with what we know about the Icelandic trading stations from other written sources: they were only used during the summers, when the foreign vessels were in Iceland, and their owners did not invest in solid infrastructure because they were not sure whether they would return the next summer. For Landey, records only exist for the 1590s.

Written sources indicate that merchants generally slept in the dwellings on land while the ship´s crew stayed on board. However, the excavations at Landey give food for thought. A Northern German merchant might have found it more comfortable to stay on board than to spend his nights in a damp and dark turf building…

References:

D. Kohl, Der oldenburg-isländische Handel im 16. Jahrhundert. Oldenburger Jahrbuch 13, 1905, 34–53.

Mehler & M. Gardiner, On the Verge of Colonialism: English and Hanseatic Trade in the North Atlantic Islands, in Peter Pope and Shannon Lewis-Simpson (eds.), Exploring Atlantic Transitions: Archaeologies of Permanence and Transience in New Found Lands. Society of Post-Medieval Archaeology Monograph 8 (Woodbrige 2013) 1-15.

Oldenburg, Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv, Best. 20, -25, no. 6.

Copenhagen, Rigsarkivet, Tyske Kancelli D 11, Pakke 28 (Island og Færøer, Supplement II, no. 25)