Keeping the Faroese bishop warm – how a tiled stove tells the story of the Reformation in the Faroes

Natascha Mehler, 16 August 2017

with Torbjörn Brorsson, Martina Wegner and Símun V. Arge

In 1557 the Reformation in the Faroes came to an end when the Faroese bishopric at Kirkjubøur was abolished and its properties confiscated by Christian III of Denmark. This was the result of a process which started in 1539 when Amund Olafson, the last Catholic bishop, was replaced by Jens Gregersen Riber, the first Lutheran bishop of the Faroes. Jens Riber stayed at Kirkjubøur until 1557 when he left to take on a new position in Stavanger. We know very little about the lives of these two bishops. However, during archaeological excavations conducted in 1955 at the site of the former episcopal residence, the remains of a tiled stove dating to the early and mid-16th century came to light which add knowledge about the daily life at Kirkjubøur.

The tile fragments were now, more than 60 years after their discovery, analyzed as part of this research project. Tiled stoves were a luxurious rarity in the North Atlantic islands. In Iceland, for example, 16th-century tiled stoves are only known from the two bishoprics at Skálholt and Hólar, the Danish residence at Bessastaðir and from the monastery at Viðey. The Kirkjubøur fragments are the only remains of a tiled stove in the Faroes. In Denmark or Northern Germany, however, tiled stoves were rather common in burgher households and those of the nobility.

19 stove tile fragments were found at Kirkjubøur, all made from red clays, moulded with relief decoration and applied with a white slip and green lead glaze. Varying fabric and decoration indicates that the tiles are the products from at least two different workshops. This means that either the tiles of the former stove were exchanged during its lifetime, or the stove was made from tiles from different workshops. The latter interpretation would be rather unusual in a continental context but all known early modern tiled stoves from Iceland were made of tiles from different workshops because access, import and maintenance were very difficult.

Stove tile made near Lübeck, with the remains of Judith and the head of Holofernes (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

The images on the Kirkjubøur tiles mirror the struggles of the introduction of the Reformation in the Faroes. All tiles show Christian or biblical motifs and themes, but while one of the identified motifs displays catholic imagery, others are clearly reformist in meaning. In many Northern European households such stove tiles decorated with Lutheran imagery were indeed used as a medium to express the Lutheran confession.

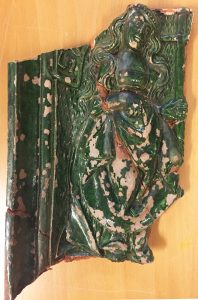

Stove tile produced in the area between Lübeck and Bremen, with the relief of probably a female Saint (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

One stove tile fragment shows a female figure with a cross in her left hand. A letter “S” is preserved, suggesting that this is a female saint such as Helena. If this interpretation holds true it would be a tile with purely Catholic imagery. The best preserved stove tile shows a bearded man in profile and the words [S]ANT PAVLO APOSTOLVS. Although this is a depiction of yet another saint – and thus rather Catholic in meaning – the letters of Paul the Apostle were often invoked by reformist theologians of Wittenberg. All other identified motifs were popular amongst supporters of Lutheranism. One fragment shows the lower body part of a female figure with a man’s head next to it. This is clearly a depiction of Judith with the head of Holofernes in her hand, a widespread stove tile motif in Lutheran contexts. And two identical tiles show the ascension of Jesus and parts of the creed of the Lutheran catechism. The surviving text reads 6 ER IST AVGEFARE[N] GEN HIMEL SITZET ZVR RECHTEN GOTES DES ALMECHTIGEN VATERS (transl. “he has ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of the Father”). The letter 6 indicates that this is the sixth stove tile in a series.

Eight fragments of these stove tiles were selected for analysis by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MA/ES), a standard method in ceramic analysis, carried out by Torbjörn Brorsson (Kontoret för Keramiska Studier). The main goal of the analysis was to determine the chemical composition of the various fabrics, with the aim to identify the workshops which produced these tiles. The results show that the tile with Paul the Apostle was made in Lübeck, and the tile with Judith and Holofernes, as well as the tile with the creed of the Lutheran catechism, in the surroundings of Lübeck. The tile with the female saint was made in the area between Lübeck and Bremen, which also includes Hamburg. This is no surprise; Northern German potters were the leading craftsmen to supply the Northern European market with stove tiles at that time.

The stove tiles were imported to the Faroes during the period when the Faroes were licensed to Hamburg citizen Thomas Koppen, between 1529 and 1553. Thomas Koppen was Oberalter of the churches in Hamburg and therefore an important figure in the process of the Reformation there. Maybe Koppen’s merchants (very likely he never visited the Faroe Islands himself) had brought the tiles from Lübeck via Hamburg to the Faroes. It is also very likely that Norwegian merchants from Bergen brought the tiles to the Faroes. The islands were closely connected to Bergen, with many ships travelling between the harbours of Tórshavn and Bergen. Lübeck merchants held a very important position in Bergen at that time and the tiles could have been brought from Lübeck first to Bergen and then went further to the Faroes.

The story that the tile finds suggest is such: a tiled stove was first erected at Kirkjubøur during the office of the Catholic bishop Amund Olafson, and fitted with tiles such as the one with the female saint. When Jens Riber took over as first Lutheran bishop in 1539 he bought new tiles from a different workshop and exchanged the purely Catholic images on his stove with motifs of the new faith. Only then could he enjoy the comforting warmth effusing from his stove without being agonized by the troubling sight of Catholic images.

References:

Julia Hallenkamp-Lumpe, Das Bekenntnis am Kachelofen? Überlegungen zu den sogenannten “Reformationskacheln”. In: C. Jäggi and J. Staecker (eds.), Archäologie der Reformation. Studien zu den Auswirkungen des Konfessionswechsels in der materiellen Kultur (Berlin 2007) 239–258.

Louis Zachariasen, Føroyar sum rættarsamfelag 1535–1655 (Tórshavn 1961), see pages 161–184.

The cultural impact of German trade in the North Atlantic

Natascha Mehler, 19 October 2016

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the North Atlantic islands of Iceland, Shetland, and to some extent also Faroe, were closely tied to the cities of Bremen and Hamburg. Merchants from these hanseatic cities regularly travelled North to exchange goods such as grain / flour, beer, timber and tools for stockfish and sulphur. In the second half of the 16th century about 500 to 750 merchants, sailors, craftsmen, priests and others from Hamburg and Bremen spent their summers in Iceland. On the other hand, a considerable number of Icelanders used Hamburg and Bremen ships to travel to the continent, e.g. to be educated in jurisprudence or theology at the universities in Copenhagen, Rostock and Wittenberg. They brought back new knowledge that changed the insular societies.

The German presence on the islands and the stay of islanders in Northern Germany had a profound impact on the North Atlantic insular societies. Tracing this impact will be the main aim of an interdisciplinary research seminar that takes place from 26 to 28 October 2016 at the museum Schwedenspeicher in Stade near Hamburg. It is organized in cooperation with the archive Stade and the museum Schwedenspeicher Stade.

The main aim of this seminar is to trace and disentangle the forms of impact. The topics and questions we want to discuss during the seminar include:

- What role did the German connections play in the assertion of the reformation in Iceland, Shetland and Faroe? What was the position of the Danish and Scottish crown? How did religious life change on the island?

- What was the cultural effect of the reformation and how did the new scholarship change the insular societies? How did knowledge transfer happen?

- What role did hanseatic measurements (e.g. the Hamburg ell) and coinage (e.g. Reichsthaler) play on the islands and how were their values converted into the Icelandic, Faroese and Shetland value system? Did the different value systems effect the economic connections?

For more information on the seminar click here to download the flyer for the cultural-impact-research-seminar.

Posted in: Announcements