Wrong place, wrong time: the theft of Gerdt Hemeling’s ship on Shetland, 1567

Bart Holterman, 28 September 2016

Sumburgh Head (Sweineburgkhaupt), the southern tip of Mainland, close to which the harbour must have been which was used by Gerdt Hemeling. Image: Wikimedia Commons

In the early months of 1568, Bremen merchant Gerdt Hemeling (the brother of the deceased Cordt Hemeling, about whose death we wrote in an earlier blogpost) complained to king Frederick II of Denmark about the theft of his ship in Shetland by a “Scottish man”. This man had promised to return his ship, or to compensate him for it, but was taken captive by Danish officials and was now in prison in the castle of Bergenhus in Bergen, Norway. Now Hemeling, a “poor and extremely desperate man”, appealed to the Danish king to compensate him for the loss of his ship and his goods, which had been thrown overboard when the ship was taken, and most of which he had to leave on the shores of Shetland.

Gerdt Hemeling had traded peacefully for years between Bremen and Shetland, staying on the islands every summer to trade commodities from mainland Europe for fish. In the summer of 1567, however, this happened to be just the wrong time and place. While he was loading his ship the Pellicaen with fish in the harbour of “Ness in Schweineburgkhaupt” (probably Dunrossness near Sumburgh head, the southern tip of Shetland Mainland), a ship appeared from Scotland with a few hundred men on board, who offered Hemeling to buy his ship or to rent it for two months. Hemeling claimed to have had no choice but to accept this offer. The men from Scotland threw all merchandise on the shore and left, never to be seen again.

Gerdt Hemeling’s case was in itself not unique. Piracy on German merchants on Shetland occured more often, especially in these years. In the previous year (1566) the Shetland merchants from Bremen filed an official complaint to the city council in which they stated that at least six of them had become the victims of robbery. Scottish pirates had attacked their ships and trading booths and stolen their merchandise, money, weapons, and sailing instruments, to a calculated total damage of 1008 thaler. Two of the pirates’ captains, James Edmistoun and John Blacader, were arrested and executed the next year by the Scottish authorities.

Gerdt Hemeling, however, found himself in a much more complicated situation. The “Scottish man” turned out to be none other than James Hepburn, 4th earl of Bothwell, an opportunistic nobleman who played a rather controversial role in high politics of his time. In 1567, when Hemeling accidentally met him, Bothwell was a man on the run. He was suspected of having murdered the second husband of Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, of having kidnapped her (possibly with her own consent), and subsequently married her. Among the Scottish nobility, tensions with the catholic queen had risen in previous years, among others about religious matters, and Mary’s marriage to the protestant alleged murderer of her previous husband proved to be the limit. A coalition of nobles revolted, and faced Mary’s army in the battle of Carberry Hill. Mary eventually surrendered and was imprisoned, finally leading to her abdication, but Bothwell fled and tried to leave Scotland by ship to Shetland.

Bergenhus castle, Bergen, Norway. The so-called Rosenkrantz tower was constructed in the 1560s by Erik Rosenkrantz. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

However, Bothwell was being followed by two Scottish lords who controlled the navy. In these chaotic circumstances, Bothwell lost one of his ships which struck an underwater rock, and desperately tried to acquire more ships for his fleet in Shetland. Luckily for him, every year there were a few German trading ships in Shetland, and thus he took Gerdt Hemeling’s ship and another one from Hamburg. However, he was not able to get rid of his persecutors, and a battle resulted in which the mast of one of the ships broke.

A storm subsequently forced Bothwell’s fleet to sail towards Norway, where he was first held for a pirate, taken captive, and locked up in Bergenhus castle by Erik Rosenkrantz, the governer of Bergenhus. When his true identity became known, Frederick II realised the potential of Bothwell in Danish captivity as a pawn when dealing with the English and Scottish crown, and had him transported to Denmark. Bothwell (who had been made duke of Orkney and Shetland by Queen Mary) promised to return these insular groups (which Christian I of Denmark and Norway had lost to Scotland in 1469 as a pawn for the dowry of his daughter to the Scottish king, which he had been unable to pay) to Denmark if the king helped him to free Mary. The Danish king never made use of this offer: Bothwell was locked up in Dragsholm castle, where he would eventually die in 1578.

And did Hemeling ever get his ship back? Frederick II was unwilling to help Hemeling directly, but stated to him twice that he could press charges against Bothwell in Denmark if he wanted to. There are no sources pertaining to a case of Hemeling against Bothwell, so it is likely that Hemeling realised that a lawsuit in Denmark in such a complicated situation would not be worth the trouble, and he must have accepted his loss.

When sailing North, beware of swimming cows and Hamburgers. The Carta Marina and the North Atlantic

Bart Holterman, 5 October 2015

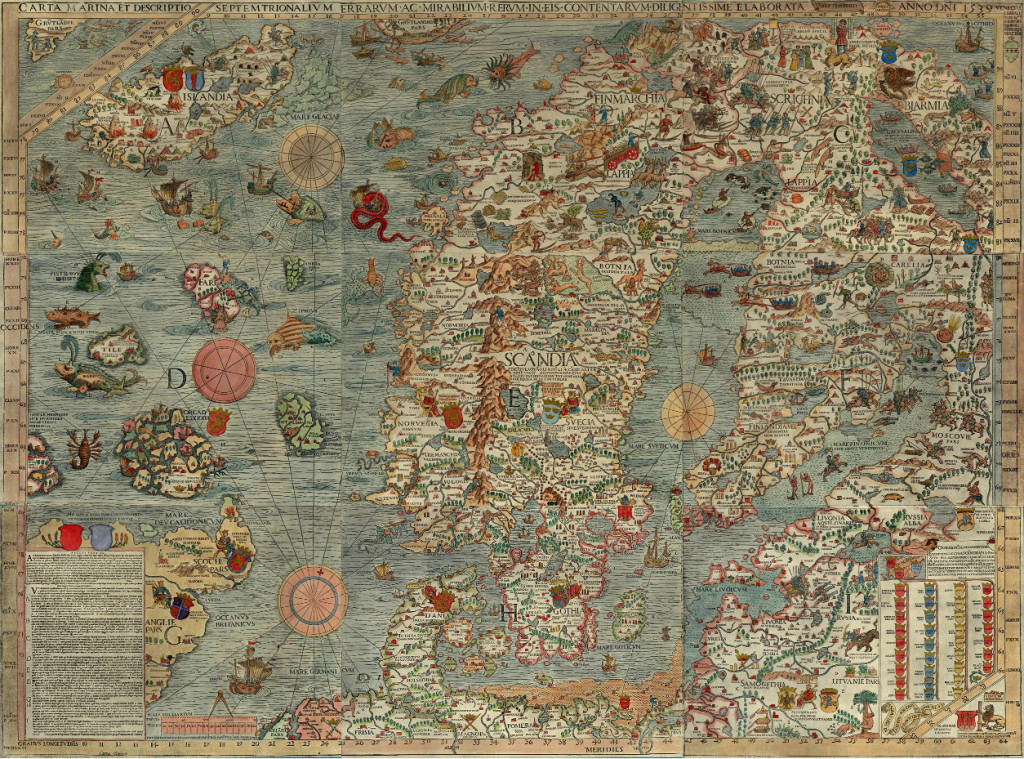

For the banner of this blog and our facebook page, we have displayed a section of the famous Carta Marina from 1539. On a first glance of the map, the many marvellous creatures that inhabit the land and the sea immediately catch the eye of the beholder, yet it also provides us with a good overview of the contemporary North Atlantic trade. Time to explore this remarkable document a bit further.

The map was made by Olaus Magnus (1490-1557), the brother of the last catholic bishop of Sweden. He had travelled Scandinavia and the lands around the Baltic Sea extensively before he was sent on a diplomatic mission to Rome by the Swedish king Gustav Vasa. He was never to return home. Dissatisfied by the Reformation in his homeland, Magnus stayed abroad, first in Lübeck and Danzig, later for a long time in Italy, soon joined by his expelled brother Johannes Magnus. In Italy he kept close contacts to learned men of his age, among others cartographers and travellers.

Under influence from these social circles, Magnus decided to transform his own knowledge about Northern Europe onto a map, which would appear in print in Venice in 1539. It was the first large-scale map of Scandinavia to be ever made, and had much influence on European cartography for the next decades. However, because of its high costs, the number of copies remained low. The map itself disappeared off the map of European learning, and was deemed to be lost since the late sixteenth century. Luckily in 1886 an intact copy of the map was discovered in the Bavarian State Library in Munich, and in 1961 another one, which now resides in Uppsala.

An explanation of the map appeared only in 1555 as Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus. In this book, Olaus Magnus described the geography, wildlife, and customs of the people of the North, illustrated with woodcuts. These woodcuts are clearly based on parts of the map, which includes many details about the people of the North, the political situation of the time, and the nature and wildlife. We can see kings sitting on their thrones, armies crossing the frozen Baltic Sea, people hunting seals, the most important towns and cities, lighthouses, whales attacking ships, enormous snakes, swimming cows and other sea monsters.

The map is divided into nine parts, marked A-I. It covers the entire Scandinavian peninsula, the Baltic, Northern Germany and the Netherlands, the entire North Sea and North Atlantic, including the coastline of Britain, the southern tip of Greenland and the mythical island Thule, known from classical geographical works. Of our interest are mainly the sections A and D, covering a large part of the North Atlantic.

Olaus Magnus probably never visited the North Atlantic himself. Instead, he had to rely on the stories and descriptions of others, for example the Northern German traders that told him about Iceland, the Shetlands and the Faroe Islands. Of the Shetlands and Faroes, Magnus must have had few information, as these archipelagos are only schematically drawn. One remarkable detail can be found on the Faroes, though, where we can see a whale being slaughtered on the shore, reminiscing a practice of hunting whales by driving them up the shore which is still practiced today.

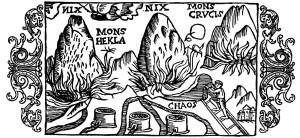

For Iceland, Magnus was clearly better informed. The Carta Marina was the first map that drew the island in its more or less actual shape. Moreover, three vulcanoes attest to Magnus’s knowledge of the high vulcanic activity on the island. The two episcopal sees, Hólar (Holensis) and Skálholt (Scalholdin), are displayed, as well as the monastery Helgafell (Abbatia Helgfiall), which was famed for its butter production (butirum). The three knights on the eastern part of Iceland should probably be seen as an indication of Danish military presence on the island.

Three volcanoes on Iceland, from Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (1555), photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Better than the natural, religious, and political situation, the map attests of the economic situation. Firstly, the main export goods of Iceland are indicated. These are, besides the already mentioned butter: stockfish, sulphur, and falcons. Stockfish was dried cod, highly valued in Europe as a preservable source of protein, and the main trade good of the arctic region. It is shown on a pile on the south coast. Just north of it, three containers of sulphur are depicted. Iceland was one of the few places where pure sulphur could be found. Sulphur, being among others a key ingredient for making gunpowder, was a highly valued substance. Finally, a gyr falcon (falco albus) can be seen on one of the northern peninsulas of Iceland. Gyr falcons are only found in arctic regions, and due to its being the largest and strongest species of falcon, it was highly valued by the nobility for use in falconry.

Apart from the export goods, the realities of the north atlantic trade are displayed in considerable detail on the map. Various trading harbours are indicated, most notably Hafnarfjörður (Hanafiord), where merchants from Hamburg had built a church. We can see ships lying at anchor at these harbours, and three tents at Ostrabord, which probably indicate the temporary booths the merchants set up on the shore and where they displayed their goods on sale during the summer.

The most important countries and cities trading with the island are also indicated. We can see a ship from Bremen at anchor near Ostrabord, an English ship which confused a whale for an island, a ship from Lübeck being attacked by whales, and a Scottish ship under attack by one from Hamburg, indicating the dominance of Hamburg in the North Atlantic trade. It was no exception that competition between merchants from different places led to violent clashes, as in 1523, when the crews of ships from Bremen and Hamburg attacked an English ship in a conflict over the rightful ownership of an amount of stockfish, resulting in casualties among the English.

These elements make the Carta Marina a wonderful visual testimony of the North Atlantic trade in the sixteenth century.

Posted in: Sources