Newspaper article: Reger Handel mit dem hohen Norden

Bart Holterman, 7 September 2017

Bart Holterman presentated the project and his own research on August 5 in Haus der Wissenschaft in Bremen. Matthias Holthaus was there as well and wrote the following article about it in the Weser Kurier of August 21, which gives a nice overview of the situation German merchants had to deal with when trading in the North Atlantic in the late Middle Ages (in German).

Posted in: Press

Keeping the Faroese bishop warm – how a tiled stove tells the story of the Reformation in the Faroes

Natascha Mehler, 16 August 2017

with Torbjörn Brorsson, Martina Wegner and Símun V. Arge

In 1557 the Reformation in the Faroes came to an end when the Faroese bishopric at Kirkjubøur was abolished and its properties confiscated by Christian III of Denmark. This was the result of a process which started in 1539 when Amund Olafson, the last Catholic bishop, was replaced by Jens Gregersen Riber, the first Lutheran bishop of the Faroes. Jens Riber stayed at Kirkjubøur until 1557 when he left to take on a new position in Stavanger. We know very little about the lives of these two bishops. However, during archaeological excavations conducted in 1955 at the site of the former episcopal residence, the remains of a tiled stove dating to the early and mid-16th century came to light which add knowledge about the daily life at Kirkjubøur.

The tile fragments were now, more than 60 years after their discovery, analyzed as part of this research project. Tiled stoves were a luxurious rarity in the North Atlantic islands. In Iceland, for example, 16th-century tiled stoves are only known from the two bishoprics at Skálholt and Hólar, the Danish residence at Bessastaðir and from the monastery at Viðey. The Kirkjubøur fragments are the only remains of a tiled stove in the Faroes. In Denmark or Northern Germany, however, tiled stoves were rather common in burgher households and those of the nobility.

19 stove tile fragments were found at Kirkjubøur, all made from red clays, moulded with relief decoration and applied with a white slip and green lead glaze. Varying fabric and decoration indicates that the tiles are the products from at least two different workshops. This means that either the tiles of the former stove were exchanged during its lifetime, or the stove was made from tiles from different workshops. The latter interpretation would be rather unusual in a continental context but all known early modern tiled stoves from Iceland were made of tiles from different workshops because access, import and maintenance were very difficult.

Stove tile made near Lübeck, with the remains of Judith and the head of Holofernes (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

The images on the Kirkjubøur tiles mirror the struggles of the introduction of the Reformation in the Faroes. All tiles show Christian or biblical motifs and themes, but while one of the identified motifs displays catholic imagery, others are clearly reformist in meaning. In many Northern European households such stove tiles decorated with Lutheran imagery were indeed used as a medium to express the Lutheran confession.

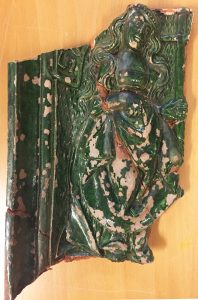

Stove tile produced in the area between Lübeck and Bremen, with the relief of probably a female Saint (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

One stove tile fragment shows a female figure with a cross in her left hand. A letter “S” is preserved, suggesting that this is a female saint such as Helena. If this interpretation holds true it would be a tile with purely Catholic imagery. The best preserved stove tile shows a bearded man in profile and the words [S]ANT PAVLO APOSTOLVS. Although this is a depiction of yet another saint – and thus rather Catholic in meaning – the letters of Paul the Apostle were often invoked by reformist theologians of Wittenberg. All other identified motifs were popular amongst supporters of Lutheranism. One fragment shows the lower body part of a female figure with a man’s head next to it. This is clearly a depiction of Judith with the head of Holofernes in her hand, a widespread stove tile motif in Lutheran contexts. And two identical tiles show the ascension of Jesus and parts of the creed of the Lutheran catechism. The surviving text reads 6 ER IST AVGEFARE[N] GEN HIMEL SITZET ZVR RECHTEN GOTES DES ALMECHTIGEN VATERS (transl. “he has ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of the Father”). The letter 6 indicates that this is the sixth stove tile in a series.

Eight fragments of these stove tiles were selected for analysis by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MA/ES), a standard method in ceramic analysis, carried out by Torbjörn Brorsson (Kontoret för Keramiska Studier). The main goal of the analysis was to determine the chemical composition of the various fabrics, with the aim to identify the workshops which produced these tiles. The results show that the tile with Paul the Apostle was made in Lübeck, and the tile with Judith and Holofernes, as well as the tile with the creed of the Lutheran catechism, in the surroundings of Lübeck. The tile with the female saint was made in the area between Lübeck and Bremen, which also includes Hamburg. This is no surprise; Northern German potters were the leading craftsmen to supply the Northern European market with stove tiles at that time.

The stove tiles were imported to the Faroes during the period when the Faroes were licensed to Hamburg citizen Thomas Koppen, between 1529 and 1553. Thomas Koppen was Oberalter of the churches in Hamburg and therefore an important figure in the process of the Reformation there. Maybe Koppen’s merchants (very likely he never visited the Faroe Islands himself) had brought the tiles from Lübeck via Hamburg to the Faroes. It is also very likely that Norwegian merchants from Bergen brought the tiles to the Faroes. The islands were closely connected to Bergen, with many ships travelling between the harbours of Tórshavn and Bergen. Lübeck merchants held a very important position in Bergen at that time and the tiles could have been brought from Lübeck first to Bergen and then went further to the Faroes.

The story that the tile finds suggest is such: a tiled stove was first erected at Kirkjubøur during the office of the Catholic bishop Amund Olafson, and fitted with tiles such as the one with the female saint. When Jens Riber took over as first Lutheran bishop in 1539 he bought new tiles from a different workshop and exchanged the purely Catholic images on his stove with motifs of the new faith. Only then could he enjoy the comforting warmth effusing from his stove without being agonized by the troubling sight of Catholic images.

References:

Julia Hallenkamp-Lumpe, Das Bekenntnis am Kachelofen? Überlegungen zu den sogenannten “Reformationskacheln”. In: C. Jäggi and J. Staecker (eds.), Archäologie der Reformation. Studien zu den Auswirkungen des Konfessionswechsels in der materiellen Kultur (Berlin 2007) 239–258.

Louis Zachariasen, Føroyar sum rættarsamfelag 1535–1655 (Tórshavn 1961), see pages 161–184.

Worth a fortune: Icelandic gyrfalcons

Natascha Mehler, 11 August 2016

Throughout the medieval and early modern period, Icelandic gyrfalcons were highly valued at the courts of European rulers and they were worth a fortune. Indeed, Frederick II (1194-1250), Holy Roman Emperor, already noted in his treatise De arte venandi cum avibus that the best falcons for use in falconry were gyrfalcons (…et isti sunt meliores omnibus aliis, Girofalco enim dicitur). The reason for this was that of all falcon species, gyrfalcons (Falco rusticolus) are the largest and most powerful. Their plumage varies greatly from completely white to very dark, of which the white variety was the most valued hawking bird in the Middle Ages, and still is today. They only inhabit sub-arctic and arctic areas, with their highest population density in Iceland (one pair per 150-300 km²). During the breeding season (roughly February to June) there are today 200-400 nesting pairs in Iceland, and in the winter the population increases to 1.000-2.5000 individuals, due to migrating birds from Greenland.

Written sources from the 16th century, when German merchants from Hamburg and Bremen dominated the trade with the North Atlantic islands, give us a better insight into the falcon business with Iceland. Matthias Hoep, a Hamburg merchant, has left behind a collection of account books (1582-1594) which show us that he traded in many commodities such as fish, timber, and tools, and specialized in the trade of falcons. Hoep employed falcon catchers to catch birds in Iceland for him and he made specific contracts with them. The books record a great number of falcons and other birds of prey that he bought from falcon catchers and which he then sold on. On 5 April 1584, Hoep made a contract with the falcon catchers and brothers Augustin and Marcus Mumme which he commissioned to travel to Iceland to catch falcons. The contract specified the bird species, the conditions of the birds upon delivery, and the prices Hoep was going to pay after the successful return of the Mummes from Iceland:

“On 5 April [1584] I have dealt in my house with Augustin and Marcus Mumme, in the name of god, that they shall sail to Iceland in the name of god, and we agreed that I will give for each pair of falcons 11 ½ daler, and 2 tercel [male falcons] for 1 falcon, and what is blank shall be counted as a red [unmoulted] falcon. But what is white and moulted once, or moulted twice and beautiful, for those I shall give them 20 daler for each falcon and 10 daler for a tercel. But what has moulted three times we shall agree upon with good will, and if god and luck provides them with white falcons, I will give the one who catches them black cloth for a jacket of 2 ½ ells, all of this is validated with a denarius dei of 1 sosling each, and both brothers have promised with an oath to bring the best birds they can get and to take no birds away, neither in Iceland nor during the journey back, until they have all been delivered to me.“

Roughly five months later, in September 1584, the brothers returned from Iceland and handed over 49 birds to Matthias Hoep.

Detail of the Carta Marina (1539) showing the coat of arms of Iceland (stockfish), with a gyrfalcon (FALCO ALBI) above.

Later documents tell us how the shipping of the falcons was done. During the 17th century, a Danish falcon ship went to Iceland annually to transport falcons from Iceland to Copenhagen. The falcons were kept below the deck and sat on poles which were lined with vaðmál. During the journey, the birds were fed with meat of cattle, sheep or birds, dipped in milk, and when they were sick, they were fed with a mix of eggs and (fish) oil. Upon arrival of the birds in Hamburg, Mathias Hoep checked their health and quality and he considered them in good state after they had eaten three times and their feathers were not broken.

Most of the birds that Hoep received were sold to English merchants such as John Mysken who bought 55 birds of prey in 1584 and had them shipped to England, most likely to be sold to the English court. It is likely that Hoep also had good contacts with Icelanders, both in Iceland and in Hamburg. His professional network may have included Magnús Jónsson (c. 1530-1591), who had studied law in Hamburg, probably until 1556. In Iceland he became chieftain and sýslumaður (sheriff) at Þingeyjaþingssýsla and Ísafjarðarsýsla, districts in the North of Iceland with a very high density of falcons. No wonder his seal from the year 1557 shows a gyrfalcon in the centre.

Seal of Magnús Jónsson, dated 1557. The priest Ólafur Halldórsson, a contemporary of Magnús Jónsson, described the seal in a poem: „Færði hann í feldi blá, fálkann hvíta skildi á, hver mann af því hugsa má, hans muni ekki ættin smá.” (transl. „he carried in a blue field, a white falcon on his shield, so that everybody shall think his family is not insignificant“).

In the second half of the 16th century, king Frederick II of Denmark-Norway (1559-1588) started to regulate the export of falcons to foreign countries. From the 1560s onwards, foreign falcon catchers needed to buy a permission (Icel. fálkabréf, falcon letter) to catch falcons.

Were falcons also caught in Shetland or the Faroes?

We have not found any written evidence for that. The obvious reason for this is that there are not many falcons around in Shetland and the Faroes. Gyrfalcons only appear as vagrant birds, and peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) exist in Shetland only in small numbers. However, it is worth pointing out that in the years 1601 to 1606 one Tonnies Mumme is recorded to have sailed each summer from Hamburg to Shetland. We do not know whether this is the same Tonnies Mumme that is reported as falcon catcher in Iceland in previous years, or whether Tonnies is related to the Augustin and Marcus Mumme mentioned above, but it seems very likely. He may have tried his luck in Shetland, or might have changed his profession and have traded in other items.

Further reading

Natascha Mehler, Hans Christian Küchelmann & Bart Holterman, The export of gyrfalcons from Iceland during the 16th century: a boundless business in a proto-globalized world. In: Gersmann, Karl-Heinz & Grimm, Oliver (eds.): Raptor and human – falconry and bird symbolism throughout the millennia on a global scale, vol. 3, Advanced studies on the archaeology and history of hunting 1 (Neumünster 2018), 995-1019.

Kurt Piper, Der Greifvogelhandel des Hamburger Kaufmanns Matthias Hoep (1582-1594). Jahrbuch des Deutschen Falkenordens (2001/2002), 205-212.

Björn Þórðarson, Íslenzkir fálkar. Safn til sögu Íslands og íslenskra bókmennta (Reykjavík 1957).

Posted in: Stories

Sailors, merchants and priests: people on board the ships heading North

Bart Holterman, 13 May 2016

The general history of the northern German trade with the North Atlantic is relatively well known but we know very little about the persons involved in this trade. This is especially true for the men that manned and sailed the ships that headed North.

Luckily, there are a couple of sources pertaining to the North Atlantic trade that give us a good insight into the people on board the ships. First, two boarding lists from Oldenburg for ships trading with Iceland in the 1580s have survived. Second, there is the magnificent book of donations of the Hamburg confraternity of St Anne, the socio-religious organisation behind the trade with Iceland, Shetland, and the Faroe Islands. From the 1530s onwards, the register lists the alms spent to the confraternity by the people on board of nearly every ship that returned to Hamburg, resulting in a more or less complete register of boarding lists.

On board a sixteenth-century ship: detail of the epitaph for the ship´s priest Sweder Hoyer (deceased 1565) from the St Jacob church in Lübeck. Note: this image does not necessarily reflect the situation on board the merchant ships in the North Atlantic.

From these sources we can learn that the number of people on board varied greatly, ranging from 77 on larger ships up to around 10 on board the smallest vessels. For Iceland, it was not uncommon to have more than 25 people on board. Ships sailing to Shetland and the Faroe Islands had less people on board, usually 15-20.

This difference in number of people on board was mainly caused by the number of merchants on board. The sizes of the crews were relatively similar on each ship, because 10 to 15 people were needed to sail the ship, regardless of its size. A typical crew consisted of:

– Skipper (schipper). He was the captain, the leader of the ship, often also one of the merchants, and (partly) shipowner.

– Helmsman (sturman), the one who steered the ship and had navigational knowledge.

– Chief boatswain (hovetbosman), the leader of the sailors.

– Schimman, the officer responsible for rigging and other technical things.

– Cook (koch).

– Carpenter (tymmerman), responsible for repairs to the ship.

– Gunner (buchsenschut), responsible for the defense of the ship.

– Barber (bartscher), who had medical knowledge, but lacked on most ships.

– 2-4 sailors (bosman).

– 1-2 ship boys (putker), young sailors in training.

Besides these, ships transported merchants and their servants, falcon catchers, priests, and passengers from the islands which used the regular traffic to travel to and from the European mainland.

Further reading:

B. Holterman, Size and composition of ship crews in the German trade with the North Atlantic islands. In: N. Mehler (ed.), Traveling to Shetland, Faroe and Iceland in the early modern period (Leiden, in press).

F. C. Koch, Untersuchungen über den Aufenthalt von Isländern in Hamburg für den Zeitraum 1520-1662. Beiträge zur Geschichte Hamburgs 49 (Hamburg 1995).

Uncovering the North Atlantic trade sherd by sherd

Natascha Mehler, 12 April 2016

When it comes to the goods transported by merchants from Bremen and Hamburg to the North Atlantic islands we have only limited sources at hand. The few extant account books list the commodities they sold to the inhabitants of the islands in return for stockfish, fish oil, sulphur or woolen cloth. But the written sources are not precise but rather general and never tell where the exported goods were manufactured. To complicate matters, (archaeological) material culture of the German period is scarce. Most of the goods traded by the Germans were bulk material such as grain or flour, cloth, timber, and beer, and to a lesser extent every day items that were hard to get on the islands: horse shoes, tools, knifes, wax etc. Many of these goods, especially those of organic material, have long been gone. Ceramics, however, are a different matter. Icelanders did not produce ceramic vessels (and the Faroese and Shetlanders only to a limited extent) which means that all pots, pans, jugs and beakers needed to be imported. A considerable amount of pottery from the 15th to 17th centuries has been found in Iceland, Shetland and Faroe but what can pottery sherds tell us about that trade?

Fragments of a so called “Schnelle”, a tankard produced in Siegburg in the 16th century, found at Tórshavn, the German trading station in the Faroe islands (photograph by Helgi Michelsen).

The sherds that have survived from excavations and in museum collections in Iceland show characteristic traits of wares common in Northern Europe. The ceramic assemblages of sites such as Gautavík (a German trading site in the East), Viðey (a monastery near Reykjavík), or Stóraborg (a farm at the South coast) consist of two distinctive ware groups: stonewares and redwares. Stoneware was used to produce drinking vessels such as jugs and beakers. They were widely traded over Northern Europe, via the river Rhine and ports of Northern Germany and the Netherlands. For the trained eye, these stonewares are relatively easy to determine. The majority stems from the famous medieval and early modern production centres along the Rhine such as Siegburg, Frechen, or Cologne; a second group can be traced back to Lower Saxony.

The origin of redwares, a general term for cooking vessels (pots, pans) and plates consisting of earthenware, is far more problematic to identify. Vessel shapes and fabrics of pottery workshops are generally very similar over a large area and it is therefore hard to determine where exactly a certain redware pot was produced. Distinguishing the redwares is mostly based on typological characteristics such as a distinctive form of the rim of a pot, but the Icelandic archaeological material is often too fragmented to allow an identification beyond doubts. However, provenancing these redwares would considerably change our understanding of the trade mechanisms and pottery consumption patterns in the North Atlantic.

Fragmented redware tripod with internal lead glaze found at the trading site of Gautavík, Iceland. It dates to the late 16th century but the place of origin remains enigmatic (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

Luckily, there are other methods than typology to identify the provenance of pottery. In recent years, ICP analysis (inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry), widely used in archaeological science, has proven to be a reliable method to determine the chemical fingerprint of the clays used for the production of ceramic vessels. ICP analysis has been applied successfully at a large number of redwares produced in Southern Scandinavia and Germany, with ground breaking work done by Torbjörn Brorsson (Kontoret för Keramiska Studier, Sweden) and Jette Linaa (Moesgaard Museum, Denmark). This means that we now have a solid base of reference material at hand which is necessary to securely identify the origin of the redwares in question. The application of the method in ceramic studies and an overview on the data reference material was presented in April 2016 at the inaugural meeting of the Baltic and North Atlantic Pottery Research Group (BNPG) which took place at the Historiska Museet Stockholm.

In summer 2016, redware fragments from selected sites in Iceland, Shetland and Faroe will be sampled in order to conduct ICP analysis. We will report on the results of the analysis, and what this means for the interpretation of the trading connections between Northern Germany and the North Atlantic islands.

Further reading:

Torbjörn Brorsson, A new method to determine the provenance of pottery – ICP analysis of pottery from Viking age settlements in Northern Europe. In: S. Kleingärtner, U. Müller, J. Scheschkewitz (eds.), Kulturwandel im Spannungsfeld von Tradition und Innovation. Festschrift for Michael Müller-Wille. Neumünster, 2013, 59-66.

Adolf Hofmeister, Das Schuldbuch eines Bremer Islandfahrers aus dem Jahre 1558. Bremisches Jahrbuch 80, 2001, 20-50.

Natascha Mehler, Die mittelalterliche Importkeramik Islands. Current Issues in Nordic Archaeology. Proceedings of the 21st Conference of Nordic Archaeologists, 6-9 September 2001, Akureyri, Iceland. Reykjavik 2004, 167-170.