Where have all the ships gone? The absence of German shipwrecks in Iceland

Bart Holterman, 22 December 2017

Mike Belasus, with Kevin Martin and Bart Holterman

Detail from Olaus Magnus Carta Marina 1539: The ship-destroying sea monster is symbolising the perils of a journey across the open ocean.

A Project on the Low German merchants’ trade from Bremen and Hamburg with the North Atlantic islands is not complete without the vessels that made trade across the ocean possible. The written sources tell us that many German ships were lost along the coast of Iceland, but until today, not a single mentioned shipwreck was found. This is not surprising, given the circumstance that underwater archaeology in Iceland is not even twenty years old.

Some facts about finding shipwrecks

The saying “Searching for a needle in a haystack” is fitting pretty well to the search for shipwrecks mentioned in historical documents, considering the abilities to determine a ship’s position in the past and the fact that 71 % of Earth’s surface is covered by water. Even today, many ships vanish without a trace. On top of that, the number of archaeologists looking for certain shipwrecks is extremely low. Therefore, most shipwrecks are found by accident and they remain more or less anonymous.

However, technology has improved and the potential for finding shipwrecks is much higher today than in the past. A number of devices can be used and combined for surveying the sea floor. A common combination is a side-scan sonar and a number of magnetometers, but this is still no guarantee for finding wrecks. When a ship is too decayed, or has settled into the sediment, the sound-rays of the side-scan sonar will not be able to produce a recognisable image. Moreover, magnetometers will not detect anomalies from the earth’s magnetic field when there is not enough metal on board the ship. Especially for medieval ships and early modern merchant vessels without guns, this can easily be the case. A sediment sonar could be a solution, which measures changes of density in the sediment with sound signals. The disadvantage is that waterlogged wood has the same density as waterlogged sediment. If a shipwreck has no denser cargo or ballast on board, the sonar will not detect density changes. Therefore such ships will remain hidden, even if an area is surveyed. Divers might be suggested as a final solution but a diver’s operating range is very limited, as he/she depends on depth, weather conditions, visibility and air supply.

The fact is that archaeologists rely in most cases on coincidences, which is how most of the known shipwrecks were found. The reason for this is that many other professions like builders, fishermen, geologists etc. spend much more time working on the sea floor than archaeologists, and sometimes stumble upon a wreck. One famous example for this is for example the “Bremen Cog” in the German Maritime Museum in Bremerhaven. A suction-excavator operator found it in the river Weser close to Bremen, when he was working on an extension of the riverbed. It became one of the most important finds in ship archaeology. Over the past decades, since underwater became an area of archaeological interest, hundreds of shipwrecks have been registered by the heritage departments of the German federal states but only a few of them could be identified by historical documents.

The author examining an anchor off the west coast of Gotland, at the site of the Visby-Disaster of 1566 (Photo: Jens Auer).

When we approach the shipwrecks from the historical documents, we have to realize that mentioned positions for lost ships are most of the time very vague. This situation can extend the search area dramatically without even knowing if the wrecks still exist as a coherent site. The conditions of the natural environment are vital to the survival of remains. Rugged coastlines, strong currents, micro-organisms, the chemical consistence of the water and the like can severely contribute to the decay of organic matter, metals and even certain types of stone. In the Mediterranean Sea, for example, ship hulls will not survive for a long time above the sea floor due to temperature, salinity and micro-organisms. Iron will soon vanish by the reaction with salt and oxygen and even marble and copper-alloys will decay. The opposite situation can be found in the Northern Baltic or the Sea Black Sea, for example. The Northern Baltic is deep, has a very low salt content and is cold. This prevents wood-decaying organisms to multiply and destruction from anchors or looting divers. The Black Sea water, on the other hand, has hardly any oxygen in a certain depth, which almost freezes time on the sea floor.

In addition, the circumstances of the sinking in connection to the natural environment play an important role. A German ship in Spanish service in 1588, the Gran Grifon, hardly left any structural remains. Another extreme example is the destruction of a united navy fleet of Lübeck and Danish ships during the Nordic Seven Years War on the west coast of Gotland in 1566. Out of thirty-seven ships, fifteen were lost and 6000 to 8000 sailors lost their lives in the so-called Visby-Disaster. Intensive archaeological diving surveys for several years could not reveal any wreck site. The ships literally vanished, most likely because they disintegrated in the storm on the rough sea floor and their remains were thrown up on the beach.

These examples shows us that a sunken ship mentioned in the historical documents does not always leave a proper wreck site. Sometimes scattered debris spread over square kilometres of sea floor can be all that is left of a ship.

The missing wrecks of Iceland

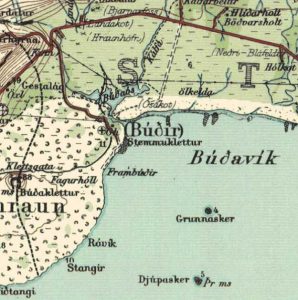

The site of the Bremen trading harbour Búðir/Bodenstede on the west coast of Iceland. It continued to be used by the Danes after 1601.

In theory, Iceland has a high potential for finding shipwrecks. Since the late 9th century, humans settle here and they had no other way than to cross the rough North Atlantic Ocean and make landfall on a rugged coast. Many ships, Norwegian, Danish, English, Low German and Dutch, evidently got lost on their route between continental Europe and Iceland. A considerable number of these found their end on the coast of Iceland, as we can read in the historical documents. Ragnar Edvardson has calculated a number of about 450 shipwrecks in Iceland, from the period from 1100 to 1900, most of which foundered on the West coast. Until today, no wreck from the period of the Low German trade has been found. The oldest ship found in Iceland is currently a Dutch merchantman, which sank in the harbour at Flatey in Breiðafjörður in 1659, and is currently under investigation by Kevin Martin. The scarcity of known shipwrecks in Iceland is not necessarily because they vanished completely, but because maritime archaeology is a very young discipline in this country and started only with sporadic projects from 1993 onwards. The relatively few inhabitants of Iceland also reduce the possibility of coincidental discoveries of wrecks due to the lack of building activities.

Vive la Coïncidence!

However, coincidences happen – even in Iceland. In 1998, an excavator hit timbers while digging a cable trench near Búðir on the Snæfellsnes peninsula in Western Iceland. They turned out to be fragments of a ship that was buried under the sand of an estuary. Some timbers and ballast stones were recovered by archaeologist Björn Stefánsson, and brought to the National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavik, were they were documented and put in storage. None of the recovered timbers was suitable for dendrochronological dating, but the ballast included stones that can possibly originate in Norway, Britain or Greenland. However, this does not give any indication were the ship was coming from, because ballast was taken from board and loaded in all harbours depending on the cargo and to adjust the angle of the ship in the water, to trim the ship. The recovered timbers give the impression of an old carvel-built ship. The material seems not to be of the finest quality, but this is hard to judge from only a handful of timbers. A promising fact is that Búðir was an important trading centre in Iceland for at least 200 years. It was already visited by Bremen merchants in the late 16th century, who called it “Bodenstede”. For a long time it was the main trading site for the Snæfellsness Peninsula, called first by cargo ships of the Low German merchants and later by Danish and Dutch ships. It was abandoned as a trading post in 1787.

The recovered ship timbers from Búðir today at the National Museum of Iceland, Reykjavik (Photo: Kevin Martin)

For this reason, we have written sources on the activities on this site including the loss of several ships during these 200 years. The problem for the identification of the accidental found ship is the fact that there was not only one ship lost near the site. We know at least about eleven ships that are reported to have been lost at Búðir and its harbour Búðavik. Of those eleven ships, one was from Bremen. It belonged to the merchant Vasmer Bake and sank in or close to the harbour of Bodenstede in 1587. This was reported by Carsten Bake, his son, who himself was involved in the Iceland trade. In 1607, a Danish ship wrecked at Búðir. For 1666, another ship sank west of Búðir. More ships sank in this area in 1724, 1728 (Danish) and 1754, and lastly, Bjarni Sívertsen’s cutter, which got lost here in 1812.

Certainly, it is possible that the ship found in 1998 is Vasmer Bake’s lost vessel from 1587, but the timbers cannot give us any more detailed information. All we can say today about the few recovered timbers is that there are five floor timbers and two fragments with an unknown function. The floor timbers indicate that the cable trench hit the wreck most likely in the bow section, leaving most of the buried remains uncovered. Each plank was attached to each frame with at least two tree nails, and each frame was connected to the keel with one or two tree nails. The dimensions of the floor timbers vary a lot, from flat and wide to high and narrow. This might be an indication that whoever built the ship faced either a shortage of crooked compass timbers, or the building did not rely on an even framing in a shell based building method, or both. However, it can also not be excluded that we face the remains of Bjarni Sívertsen’s cutter from 1812. Only future investigations might give us an answer.

References:

Edvardson R. and Grassel Ph., The Potential of Underwater Archaeology in the North Atlantic. In: N. Mehler, Travelling to Shetland, Faroe and Iceland during the 15th to 17th centuries (in press).

Stefànson, B., Skipsviðir úr Búðaósi. Rannsóknaskýrslur fornleifadeildar 1998. Fornleifadeild þjóðminjasafns Íslands, Reykjavik 1998

Posted in: General, Reports, Stories

What did the German trading stations in Iceland look like?

Natascha Mehler, 27 April 2017

The Danish trading station at Grundarfjörður, as depicted in the 1790s. Before the Danes took over the trading post in the early 17th century it was in the hands of German merchants.

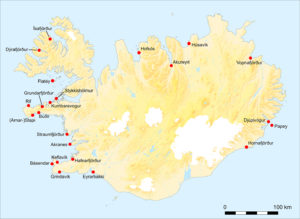

In the 16th century there were approximately 25 trading stations in Iceland which were regularly frequented by merchants from Bremen, Hamburg, Oldenburg or Lübeck. Most of these stations lay in the western part of the island, around the Snæfellsnes and Reykjanes peninsulas and in the Westfjords, because these were the areas where most fishing settlements were located and where cod, which was transformed into the main trading commodity stockfish, was abundant.

German trading stations in Iceland. Landey is near Kumbaravogur (map by Libby Mulqueeny, Mark Gardiner and Natascha Mehler).

It is difficult to tell what these German trading stations looked like because none have survived until today. In 1604, the Danish king Christian IV ordered to tear down all German buildings in Iceland, as a consequence of his imposition of the Danish trade monopoly (1602–1787). During the early 17th century many of the German trading stations (such as Grundarfjörður in the image above) were taken over by Danish traders and subsequently developed into permanent and more substantial settlements, many of which still exist today. What we don’t know is whether the Danish traders really tore down the German buildings, as was the will of the king, or simply re-used the buildings and infrastructure. The latter would certainly have been more practical in a country where building material was scarce.

Luckily, a handful of German trading sites did not develop into modern settlements and remains have survived until today. One of them is situated on the small tidal island of Landey at the northern side of the Snæfellsnes peninsula, near the present farm of Bjarnarhöfn. Written sources mention a trading post visited by merchants from Oldenburg and Bremen in the 1590s, but the amount of information from the surviving documents is very low. In 1593, Carsten Bake from Bremen acquired a three-years license for the harbour, and afterwards the harbour was given to the count of Oldenburg. In 1599, a request by the count to renew the license for Landey was denied by the Danish king because it was already in use by someone else. Who this person was is not mentioned.

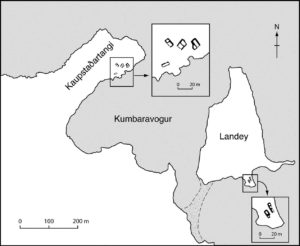

Ruins of German trading stations at Kaupstaðartangi and Landey (map by Mark Gardiner, Natascha Mehler and Libby Mulqueeny).

Today, Landey is a small island only used by sheep for grazing. The outlines of two buildings are clearly visible. They are situated on a small plain near a beach that was used as a landing site, to pull up small boats. The western side of the island faces a bay called Kumbaravogur, and on the other side of that bay lies Kaupstaðartangi, a headland where the remains of a trading station called Kummerwage have survived. This close proximity could be the reason why Landey started to be used as a trading post in the first place, as Kummerwage had been a harbour of Bremen merchants for a long time, but was given to Joachim Kolling from Oldenburg in 1580. Bremen tried hard to get the harbour back, but without success. The merchants of Bremen must have tricked the Danish king in requesting a license for the nearby Landey. When the king realised his mistake he included the clause that the license would go to Oldenburg after the Bremen one expired.

The ruins of two buildings at Landey (centre), on a green plain overlooking the landing site (image Natascha Mehler, 2016).

A trial excavation conducted with Fornleifastofnun Íslands at Landey in the summer of 2016 has shown that both buildings on Landey were indeed dwellings, although rather simple constructions. The walls were built in the Icelandic way, made of turf with stone linings. A fire place was discovered in the western building and no signs of furniture or other equipment were found. However, ten fragments of a ceramic cooking pot made of red earthenware were discovered. ICP-MS analysis of the sherds (conducted by Torbjörn Brorsson, KKS) has shown that the pot was made in Bremen, or in very close vicinity thereof (e.g. in Oldenburg).

The trial trench through the western building at Landey. The outlines of the building are clearly visible, as is the turf construction of the wall (image Vilmundur Pálmason, 2016).

The building to the east has two inner partition walls which indicates that it could have been used as a storage facility. Taking the scarce written and archaeological evidence together we can conclude that the buildings were indeed dwellings of some sort but only used for a very short time. This corresponds well with what we know about the Icelandic trading stations from other written sources: they were only used during the summers, when the foreign vessels were in Iceland, and their owners did not invest in solid infrastructure because they were not sure whether they would return the next summer. For Landey, records only exist for the 1590s.

Written sources indicate that merchants generally slept in the dwellings on land while the ship´s crew stayed on board. However, the excavations at Landey give food for thought. A Northern German merchant might have found it more comfortable to stay on board than to spend his nights in a damp and dark turf building…

References:

D. Kohl, Der oldenburg-isländische Handel im 16. Jahrhundert. Oldenburger Jahrbuch 13, 1905, 34–53.

Mehler & M. Gardiner, On the Verge of Colonialism: English and Hanseatic Trade in the North Atlantic Islands, in Peter Pope and Shannon Lewis-Simpson (eds.), Exploring Atlantic Transitions: Archaeologies of Permanence and Transience in New Found Lands. Society of Post-Medieval Archaeology Monograph 8 (Woodbrige 2013) 1-15.

Oldenburg, Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv, Best. 20, -25, no. 6.

Copenhagen, Rigsarkivet, Tyske Kancelli D 11, Pakke 28 (Island og Færøer, Supplement II, no. 25)

Medieval Stockfish recipe: Stockfish with peas, apple, and raisins

Bart Holterman, 14 July 2016

On the 11th of June 2016, a “Gastronomic stockfish symposium” took place in the city of Bergen, Norway, during the International Hanseatic Days 2016. The symposium highlighted the important role of dried fish for the history of the city. After all, without the high demand for stockfish in pre-modern Europe the city would probably never have become the medieval and early modern trading hub for northern Europe. Until c. 1500 stockfish coming from northern Norway and Iceland was brought to Bergen, and from there traded with merchants from the European mainland and the British islands, in exchange for grain and other commodities. This led to the establishment of the Hanseatic Kontor, the remains of which still exist as the Tyskebrygge quarter in the city, dominated by merchants from Lübeck, who had a near monopoly on the stockfish trade for centuries.

Topics during the symposium were very diverse, illustrating the multi-faceted influence of stockfish on the economy and culinary culture of Norway and the rest of Europe, in the past and today. The papers presented ranged from the influence of climate change on cod stocks to the culinary stockfish traditions on the Iberian peninsula, in Upper Franconia, and in Northern Italy. In the latter case, there even exists a stockfish brotherhood which seeks to preserve the culinary stockfish tradition in Italy. All presentations (with pdf files and videos) can be found here. I presented the stockfish consumption in medieval Germany, combining Hans Christian Küchelmann’s archaeozoological research and my own, based on written sources such as cook books.

This provides the perfect opportunity to present another medieval stockfish recipe which we tested a while ago: stockfish with peas, apple and raisins. As the name suggests, the recipe is an example of the same typical medieval combination of hearty and sweet tastes which was also prevalent in the previous recipe of Spanish puff pastry, and which might seem peculiar to modern taste. It is derived from a fifteenth-century manuscript from Flanders which is being edited by Christianne Muusers on her wonderful website Coquinaria. She interpreted the recipe as a typical winter recipe, since all ingredients were available in dried form at the time. We took fresh or deep-frozen ingredients (except for the stockfish), which tasted just as well. For Muuser’s transcription and interpretation of the recipe, see this page.

Cooking time: ca. 1 hour (+ 1,5 day preparation)

Ingredients (2-3 persons):

- 100g stockfish (makes about 200g fish meat when soaked an cleaned)

- 200g peas

- butter

- 1 apple, in pieces

- 1 large onion, sliced

- 100g raisins

- pepper

- cardamom

- mixture of cinnamon, cloves, and mace (or nutmeg)

- ginger powder

Preparation:

- Hammer the stockfish well for a while (if needed: some stockfish is sold pre-hammered). Soak the fish in water for 1-2 days, refresh the water a couple of times a day. When the fish is well soaked, remove the skin and bones. Take care to remove all the small bones!

- Fry the onion until golden. Add the apple and stockfish pieces and let it fry for a while, then sprinkle the spices over it.

- Add the peas and some water, stir and let it simmer with a closed lid on low fire, 20-30 minutes.

- Add the raisins during the last 10 minutes.

- Serve hot.

Project presentation at the 18th Meeting of the ICAZ Fish Remains Working Group (FRWG) in Lisbon

Hans Christian Küchelmann, 8 January 2016

On the 30th of September I held a presentation at the 18th Meeting of the Fish Remains Working Group in Lisboa. The Fish Remains Working Group (FRWG) is a subject specific working group of the International Council for Archaeozoology (ICAZ), operating since 1980 with regular biennial research meetings and publications on archaeological fish remains. Its 18th meeting was entitled “Fishing through Time – Archaeoichthyology, Biodiversity, Ecology and Human Impact on Aquatic Environments” and was held in the Museu da Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa from the 28th of September to the 3rd of October 2015. For further information on the programme of the conference see the book of abstracts.

On the 30th of September I held a presentation at the 18th Meeting of the Fish Remains Working Group in Lisboa. The Fish Remains Working Group (FRWG) is a subject specific working group of the International Council for Archaeozoology (ICAZ), operating since 1980 with regular biennial research meetings and publications on archaeological fish remains. Its 18th meeting was entitled “Fishing through Time – Archaeoichthyology, Biodiversity, Ecology and Human Impact on Aquatic Environments” and was held in the Museu da Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa from the 28th of September to the 3rd of October 2015. For further information on the programme of the conference see the book of abstracts.

The theme of the conference fit perfectly to one of the research goals of our project, which I presented within the session “Multi-disciplinary Approaches to the Study of Fish Remains: Archaeology, written and illustrated Sources”. My presentation was entitled “Hanseatic trade in the North Atlantic: the archaeozoological evidence” and its main aim was to introduce our new research project to the archaeo-ichthyiological community, to inform about the historical background, to present an overview of the evidence accumulated so far, to show the potentials and limitations of the data, and to present preliminary results.

The conference was a fantastic opportunity to get in contact with colleagues working on related topics. For example Jennifer Harland or Rebeccca Nicholson, who are working on fish remains from medieval sites in Scotland and Orkney, James Barrett who analysed the fish bones from the wreck of the Mary Rose (AD 1545), Lembi Lougas who presented material from two hanseatic wrecks in Tallinn, and Jan Bakker, who prepared a poster on fish remains from the hanseatic city of Cologne. Most important was a meeting with James Barrett, head of the international project “The Medieval Origins of Commercial Sea Fishing”, based in Cambridge. We discussed the possibilities for future cooperation between the two projects.

Apart from the scientific part, the organisers provided a fantastic field trip, which included a visit to the fish market of Setubal.

A tusk (Brosme brosme) at the fish market of Setubal. The tusk is one of the species prepared as stockfish in the North Atlantic and traded by Hanseatic merchants, although not in large quantities. Remains have been found for instance in medieval Duisburg. Photo: Hans Christian Küchelmann

Posted in: Reports

The 14th International Symposium on Boat and Ship Archaeology in Gdańsk/Poland 21.-25. September 2015

Bart Holterman, 25 November 2015

Group photo in front of the medieval crane in Gdańsk made by Paweł Jóźwiak from the National Maritime Museum in Gdansk.

From September 21st until September 25th, I participated in the 14th International Symposium for Boat and Ship Archaeology (ISBSA 14) in Gdańsk, Poland. My contribution was a talk with the title: “Those bits and pieces from the Baltic shores – Evidence for medieval shipping along the German Baltic Sea coast”. Even though this topic seems to be a bit farfetched considering the topic of our project “Between the North Sea and the Norwegian Sea”, it bears an important insight into the principles of technical change in medieval and early modern shipbuilding. Moreover when dealing with the North Atlantic trade we face the problem of a lack of archaeological source material. There are several reasons for this situation. The wrecks we know today from the southern North Sea coast are found in the rivers or on land within towns. Here they are often better protected than in the open sea. Some wrecks, foremost in the Netherlands, were found in the Wadden Sea but this is quite rare and requires a certain level of sediment coverage of the site to protect the wreck from wood-degrading microorganisms. Therefore it is not easy to find wooden wrecks in the North Sea. Moreover, the conditions for archaeological documentation are difficult due to weather, tides and swell in the rather unprotected sea. At the destinations of trade in the North Atlantic, ship archaeology is in a very early stage, especially in Iceland. As a consequence we depend on material evidence from for example the Baltic Sea to construct a model of development in shipbuilding that might have influenced the North Atlantic trade of the merchants from Hamburg and Bremen.

The presentation at ISBSA 14 focused on development processes in medieval shipbuilding, which was based on tradition handed over from one generation to the next without the use of written documents, drawings or formulas. An important aspect of the examination was the possibility of changes in shipbuilding by technical transfer between different building methods, in particular between native and introduced methods. Due to the fact that only a very limited number of medieval ship finds along the German Baltic coast are properly documented, this study was mainly based on re-used ship timbers and fragments found in town excavations. Still these bits and pieces give enough technical data for comparative analyses.

The result of this research confirms that shipbuilding methods did not just change without reason. Similarly, technical transfer did not just take place because of the presence of ships built with a different method in the same waters. In fact, technical transfer seems to have been the last choice for changes within traditional building techniques in the medieval period. Changes appear to be alterations within traditional knowledge. The main reasons for changes are economical and aim for greater shipping capacities and rationalisation or simplification of the building process.

What does this mean for the project? Towards the end of the medieval period, the building of ships with flush outer planking appeared in northern Europe. It often has been assumed that the knowledge to build ships in this fashion was simply copied from foreign ships. Instead, the archaeological evidence points towards a development or self-invention of flush-planked carvel-built vessels from within the building traditions of the clinker or Kollerup-Bremen Type building methods. Could these changes, that took place in the second half of the 15th century, have been decisive for the German merchants’ choice to sail the North Atlantic to trade?

The results will be published in the Symposiums proceedings.

Posted in: Reports