Immer Weiter – Fragen und Antworten, Teil 2

Bart Holterman, 23 May 2023

(for English see below)

Hier beantworten wir die Fragen, die Besuchenden der Ausstellung „Immer Weiter – Die Hanse im Nordatlantik“ gestellt haben. In diesem zweiten Teil geht es um die Fahrt zwischen Norddeutschland und den Inseln und das Leben an Bord.

Wie lange war man damals von Bremen nach Shetland unterwegs?

Die Dauer der Fahrt zwischen Norddeutschland und Shetland war stark vom Wetter abhängig, vor allem von der Windrichtung und -stärke. Einige Tage bis einer Woche war man jedoch sicher unterwegs. Der Bremer Schiffer Brüning Rulves beschreibt zum Beispiel in seiner Memoiren eine Reise von Bremen nach Shetland im Jahr 1551, die vier Tage im Anspruch nahm.

Wie sicher waren die Schiffe im Vergleich zu heutigen Schiffen? Gab es ein Rettungskonzept?

Obwohl die meisten seefahrenden Schiffe sehr stabil gebaut waren, war die Seefahrt sehr viel gefährlicher als heutzutage. Dabei war es nicht sosehr der Bau des Schiffes, sondern die Elemente, die die größte Gefahr darstellten. Das Risiko in einem Sturm zu geraten und Schiffbruch zu erleiden war reell. In so einem Fall gab es kein Rettungskonzept, und konnte man nur hoffen, es zu überleben.

Haben sich die Leute an Bord mal geprügelt?

Das Zusammenleben vieler Leute auf engstem Raum während eines langen Zeitraums führte selbstverständlich zu Spannungen und nicht selten auch zu Prügeleien. Unter anderem aus diesem Grund herrschte an Bord eine strikte Hierarchie, wobei der Kapitän die oberste Befehlsgewalt hatte. Laut dem hansischen Seerecht war es ihm erlaubt, seine Besatzungsmitglieder (einmal) zu schlagen. Trotzdem liefen solche Situationen manchmal aus dem Ruder, wie zum Beispiel bei dem Tod des Bremer Schiffers Cordt Hemeling in Shetland im August 1557.

Was hat man damals an Bord von Schiffen gegessen und getrunken?

Auf längeren Reisen konnten natürlich keine leicht verderbliche Nahrungsmittel mitgenommen werden. Deswegen hat man vor allem getrocknete oder gesalzene Lebensmittel gegessen, wie Schiffszwieback und gesalzenes Fleisch. Auch Stockfisch und getrocknete Erbsen und Bohnen werden regelmäßig in Proviantlisten erwähnt. Getrunken hat man dabei hauptsächlich Bier. In Rechnungen für Seereisen wird regelmäßig einen Unterschied zwischen Schiffsbier gemacht: Bier das man an Bord getrunken hat bzw. das als Handelsware dienende Bier.

English version

Here we answer the questions which were asked by visitors of our exhibition „Immer Weiter – Looking In From The Edge“. This second part bundles the questions about the journey between Northern Germany and the islands and life on board.

How long did it take to travel from Bremen to Shetland in those days?

The duration of a ship’s journey depended for a large degree on the weather conditions, especially the wind direction and speed. A couple of days until a week was a likely duration for the journey from Northern Germany to Shetland. For example, the skipper Brüning Rulves from Bremen mentions in his memoirs a journey from Bremen to Shetland in 1551 which lasted four days.

How secure were historical ships in comparison to modern ships? Was there a rescue plan?

Although most seagoing ships had quite sturdy constructions, seafaring in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period was much more dangerous than nowadays. It was not so much the construction of the ship, but the elements which were dangerous. There was a high risk of getting caught up in a storm and to suffer shipwreck. In those cases there were no rescue concepts; one could only hope to survive it.

Did the people on board fight now and then?

The cohabitation of many people in a cramped space during a large period of time of course led to tensions, and not rarely to violence. Among others for this reason, a tight hierarchy prevailed on board, with the highest authority in the hands of the captain. According to Hanseatic maritime law, he was allowed to hit the others on board (once) as a disciplinary measure. However, this didn’t prevent the violence getting out of hand sometimes, such as in the case about the death of Bremen skipper Cordt Hemeling in Shetland in August 1557.

What did they eat and drink on the ships back in the day?

Perishable foodstuffs of course could not be taken on long journeys. For this reason the people on board mostly lived on dried and salted food, such as ship biscuits and salted meat. Dried peas and beans and stockfish are other examples of food which are regularly listed as provision on ship journeys. It was mainly washed down with beer. Accounts for fitting out merchant ships regularly make the distinction between ship beer and merchant beer, of which the former was drunk on board, whereas the latter served as merchandise.

Posted in: Exhibition, General

A very Cold Case: the Death of Cordt Hemeling revisited

Hans Christian Küchelmann, 6 March 2023

& Hannah Meine

Back in 2016, we wrote on this blog about the peculiar death of Bremen skipper Cordt Hemeling in Shetland in August 1557. Hemeling was lying with his ship in Qualsunt (Whalsay) and was found dead in his bed one morning, ten to twelve days after a fight with two of his crew members. The ship’s carpenter Gerdt Breker, who had injured Hemeling’s hand on that occasion, was subsequently accused of manslaughter, forced to sign a confession of guilt and to pay a compensation to Hemeling’s family. Back in Bremen he raised a court case against this accusation, pleading to be not guilty of Hemeling’s death.

On a summer evening in 2021, I met with a friend of mine, the physician Hannah Meine, and we came to talk about the case. I wanted to know, if the evidence given in the related 16th century documents would allow inferences about the reason for Cordt Hemeling’s sudden and unexpected death, viewed with today’s medical knowledge. Is it possible to die from a hand injury? And as a consequence: was Breker falsely convicted of manslaughter?

For a reliable medical assessment, it is important to know as precisely as possible what happened to the deceased before his death. Luckily, the medical information contained in the documents about the case indeed allows us to narrow down the possible causes of death and to exclude others.

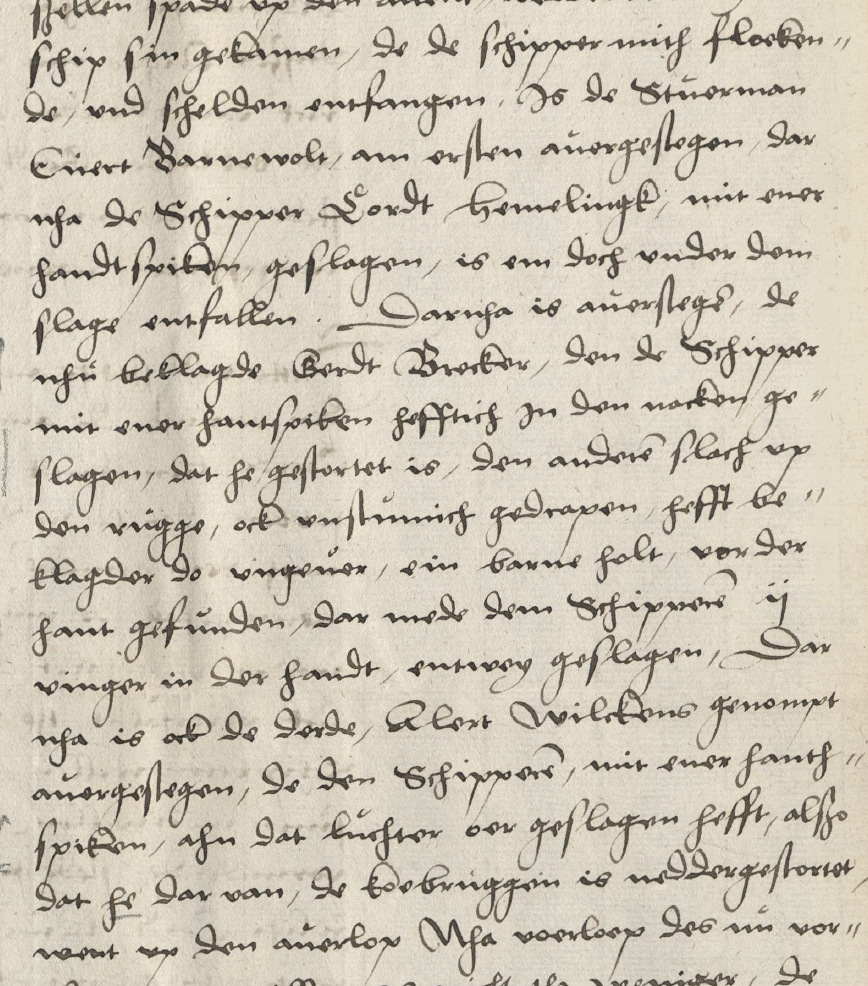

The court case lasted until 1560 and produced extensive records with testimonies about what happened in the summer of 1557 from the defendant, the accusants and of the foud (governor) of Shetland, Olave Sinclair. The original documents are stored at the Staatsarchiv Bremen and an English summary has been published by Ballantyne & Smith (1999, 73-74, 78, no. 110, 118). See also Holterman (2020, 150, 216-218, 224, 357). Transcripts and facsimiles of the documents are available in HANSdoc (Holterman & Nicholls 2018). We will concentrate here only on wordings in the documents shedding light on the constitution of Cordt Hemeling.

According to the witness account of Gerdt Breker, given in the letter of his lawyer Dirick von Minden of 7th of February 1558, there had been increasing tensions between the skipper Cordt Hemeling and his crew for a while:

„Sette und ßegge anfencklick wahr, ock allenn den bewust, de am leschen mit dem schipper Coerde Hemelinck, dem godt gnade, geßegelt hebben, dat he in der tidt, veil unwillenn, mith dem gemenen schepes geßellen, offte deneren gehatt, de mit honischen und troetzegen worden uthgehalet, derhalven ße unvormitlick vororsaket, tho veil malen umme gedachtes schipperen willen, dat schip tho rumende, und sinen moetwillen (umme ein grotter quaet tho vormidende) stede gegeven hebben, is doch zelige Cordt Hemelinck, de schipper, doch vorgedachte gedult der gemenen schepes dener, in ßynem avermode, nicht gestillet, den dagelickes de overhant meir genamen.“

One day, three crew members, the helmsman Evert Barnewolt, the carpenter Gerdt Breker and Alert Wilckens, were sent with a boat (schuete) to Laeß foerde (Laxfirth) to deliver some goods. According to Breker, the unloading took longer than expected for necessary reasons (uth noetwendigen orsaecken) and the crew returned to the ship late in the evening. They were welcomed by the skipper with curses and scolding. When Evert Barnewolt and Gert Breker came aboard, they were both hit by the skipper with a handtspike, a wooden rod used to turn the capstan. Gerdt Breker received a heavy blow in his neck and another one on his back and fell on the ship. He then took a piece of firewood lying around and hit the skipper, injuring two of his fingers. When Alert Wilckens, the third crew member, came aboard, he hit the skipper with a handtspike on the left ear, causing him to fall on the upper deck (averlop):

„[…] de de schipper mith floekende und schelden entfangen, is de stuerman Evert Barnewolt am ersten avergestegen, dar nha de schipper Cordt Hemelingk, mit ener handtspiken geslagen, is em doch under dem slage entfallen. Darnha is averstegen de nhu beklagde Gerdt Brecker, den de schipper mit ener hantspiken hefftich in den nacken geslagen, dat he gestortet is, den anderen slach up den rugge, ock unstummich gedrapen, hefft beklagder do ungever ein barne holt, vor der hant gefunden, dat mede dem schipperen II vinger in der handt, entweg geslagen. Dar nha is ock de derde, Alert Wilckens genompt avergestegen, de den schipperen mit ener hanthspiken ahn dat luchter oer geslagen hefft, alßo dat he dar van de koebruggen is weddergestortet, wert up den averlop.“

(letter of Dirick von Minden 7. 2. 1558).

After this incident, the dispute was settled and Cordt Hemeling lived and worked with his crew normally for ten to twelve days, even with the guys he had that quarrel with the other day. He ate with the other merchants, went on the island to buy sheep and constructed a hut and a bed on the island together with his carpenter. He even took part in the work itself, e. g. by nailing. He did not accuse Gerdt Breker of anything, except for the pain of his fingers:

„Nha voerloep des nu vorgedachten unwillen is nicht tho weniger de schipper darnha dagelickes by de 10 offte 12 dagelanck, mit ßinem volcke, ock mith den hantdadigen tho lande gefaren, darmede sampt anderen koepluden gegeten und gedrunckenn, ane jenigen ovell moet, ock tho twen malen sulvest up den eylanden mede geweßen, und schape gehalet, middeler wyle Gerdt Breker nergens mede beklaget, den allene van wegen siner finger ith.“

(Letter of Dirick von Minden 7. 2. 1558).

„Item dat de schypper Cordt Hemelinck selyger darna myth dem folke gegeten unde gedrunken, tho lande unde up de ohe gefaren, dar bygestan, do myn principal de boden up dat landt tymmerde, des gelyken de koien yn der boden, vor den schypper, dar he em ock sulvest thogelanget, wes Gerth tho donde hadde, van nagelen unde anderen.“

(letter of Dirick von Minden 1. 2. 1559).

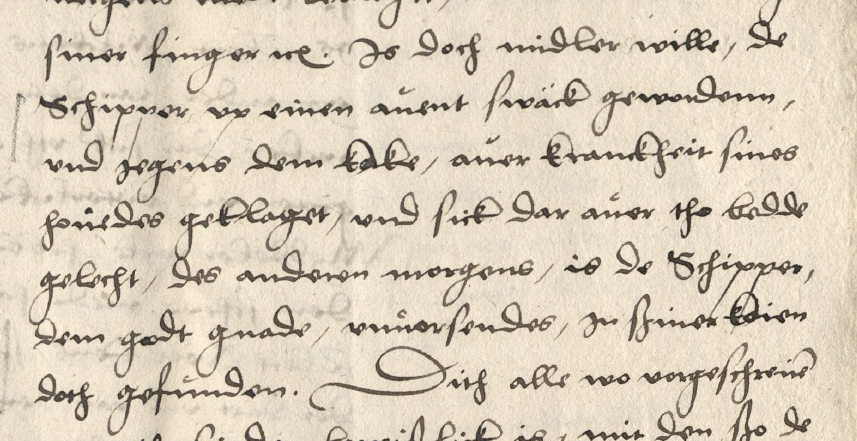

After ten to twelve days Cordt Hemeling felt weak, reported a headache to the cook and went to bed. The following morning, he was found dead in his bead:

„Do doch midler wille, de schipper up einen avent swack gewordenn, und jegens dem koke aver kranckheit sines hovedes geklaget, und sick dar aver tho bedde gelecht, des anderen morgens is de schipper, dem godt gnade, unvorsendes in ßiner koien doth gefunden.“

(letter of Dirick von Minden 7. 2. 1558).

Gerdt Breker claims in his defence that it cannot be proven that the injury he admits to have inflicted upon Hemeling is related to his death:

„Dewile den gebedenden heren, nemandes de dar levet mit warheit kan gudt don, dat de schipper Cordt Hemelinck van dem slage, den em boklagder Gerdt Breker geslagen, gestorven ßy, den hefft dar nha 10 offte 12 dagelanck alle sinen vorigen handell noch gefoert, mith dem nu beklagden, sampt anderen sunder jenigen ovelmoet, gegeten und gedruncken.“

(letter of Dirick von Minden 7. 2. 1558).

His accusers, among them Cordt Hemeling’s brother Gerdt Hemeling, claim that there is no alternative explanation for the cause of death of Hemeling other than that he died from the blow dealt to him by Breker (letter of Gerdt Hemeling 12. 12. 1559). The arguments are repeated several times in the different documents with no further relevant details given, except for two witness accounts describing different kinds of pain. Hermen Schroder reports that Cordt Hemeling complained about pain of the heart, while Diderich Snelle reports of pain of the (left) side of the body:

“dann idt secht Hermen Schroder mynn zelige broder hebbe umme wedaghe des hertenn, unnd Diderich Snelle secht he umme wedage der syden geclaget hebbe.”

(Letter of Gerdt Hemeling 12. 12. 1559).

„[…] dan obwol Hermen Schroder gezeuget, Cordt Hemeling saliger habe den abent vorseinen lesten abscheide umb wehetage deß hertzenn geclaget, unnd Diderich Schnelle saget van wehetage der linckeren seiten, so konen oder mugen dennoch die publicierte attestationes darauß alße streitich keines weges erachtet, noch viel weiniger als undichtich rejiciert und vorworffenn werden, dweile beide wehetage in una eademque parte corporis, und alßo ann einem orde deß leibes befunden, unnd wol geschehen kan, daß ein mensch zugeleich in der seitenn und umbs hertze wehetage habe, unnd dennoich itzt uber die seitenn, dan ubers hertze clage, zu deme da todtlige kranckheit vorhanden, gibt die vernufft und erfarenheit genoichsam, daß als dan daß hertze, welchs gemeinlich in der linckern seiten, und nicht in der rechtern seiten zu sitzen pflecht, am meisten periclitiert, beengestiget und gekrencket wirt. Derhalbenn, wer sagt, daß ehr schmertze umbs hertze habe, der gibt auch zuvormarchenn, daß im die linckern seitenn mit wehetagenn behafftet.“

(Letter of Dirick von Minden 15. 1. 1560).

Do these documents allow conclusions about the cause of Cordt Hemeling’s death from a modern medical perspective? Cordt Hemeling was reported to have been injured on his hand. Since he was apparently able to take part in construction work in the days following the quarrel, including himself nailing, the injury cannot have been more than a spraining or a fracture of a few hand bones. Otherwise he would have been severely impaired in his action. An injury of the hand cannot cause death itself, except in case of a blood poisoning, which could be caused by a wound getting infected with germs. This, however, would have affected Hemeling’s ability to use his hand and his condition would have worsened gradually, including a state of fever. The witness accounts instead report that he was well and acted normally during the days between the quarrel and his death.

Considering the reported chest pain, an illness unrelated to the preceding quarrel could have been responsible for his unexpected exitus. A cardiac infarction or less likely a pulmonary embolism can show symptoms of chest pain. The likelihood of cardiac infarctions raises with age. Unfortunately, we do not know Cordt Hemelings age, but given the fact that he was in command of a ship as a skipper and is included in the book of citizens of Bremen, it is unlikely that he was younger than 30 and might well have been older (see also the blog post about the career of Brüning Rulves).

A rib fracture could also cause chest pain, but is not likely here because it would have resulted in intense pain immediately after the downfall, not with a delay of 10-12 days.

The report of a headache preceding his death could be a hint towards a head injury following the blow with the handtspiken on his left ear or the subsequent downfall on the upper deck. When some venous vessels are ruptured by a heavy concussion, a slow bleeding is possible, which gradually claims space between the brain and the skull bone. Once the brain is crimped too much, the patient becomes drowsy and loses consciousness until death, which might occur even days after the blow to the head was inflicted. The reported 10-12 days between injury and death are a possible timespan for this kind of correlation.

Summarizing the historic evidence, we may look at the case from a juristic perspective. We have to suppose that all witnesses made their testimonies in all conscience. At least neither the other crew members nor the prosecutors contradicted the presentation of the events given by the accused Gerdt Breker. The only discrepancy disputed in the documents is about the kind of pain reported by Cordt Hemeling the night before his death. This discrepancy cannot be solved anymore, but assuming the reported pain was related to his sudden death, both observations medically lead to possible or likely causes of death, which are certainly not related to the hand injury caused and admitted by Gerdt Breker. The argument that there is no possible alternative explanation for Cordt Hemeling’s death, brought forward by the prosecutors (e. g. letter of Gerdt Hemeling 12. 12. 1559) is rather weak, at least in a jurisdiction in which the principle in dubio pro reo should be applied. From the medical perspective, other explanations for this sudden death are definitely possible and likely. Furthermore, a causal relation to the hand injury can be excluded. A cardiac infarction would have been completely independent from the events 10-12 days before the death. A brain bleeding, following a concussion, could have been related to a possible head injury caused by the blow with the handtspiken on Hemeling’s ear or the subsequent downfall on the averlop. This blow was, however, inflicted to Hemeling by Alert Wilckens. It remains rather peculiar why none of the involved parties demanded a closer investigation of the role of Alert Wilckens in Hemeling’s death. While both crew members feared penalty in Shetland initially (see e. g. letter of Dirick van Minden 7. 2. 1558), later accusations concentrated solely on the carpenter, whereas Alert Wilckens was not mentioned anymore in the documents.

One more juristic aspect is relevant here: According to the then valid Hanseatic ship’s law, the skipper had the right to hit his crew members once with his hand or fist as a punishment, but he was not allowed to hit twice, in which case the crew member had the right to defend himself:

“[…] und isset dat de meester eenen slaet he is hem sculdich te verdraghen eenen slach mitter hant oft mitter vust men sloghe men eenen meer he mochte sich wol weren […]”

(Vonnesse van Damme § 20, 14th century; Jahnke & Graßmann 2003, 36;

see also Roles of Oleron of ca. 1266 § 12 and Stadtrecht Hamburg of 1497 Schiffrecht § 20).

Therefore, Breker had the law on his side when he hit Hemeling, but Alert Wilckens’ blow against Hemeling was illegal. Indeed, lawyer Dirick von Minden refers to this law without explicitly stating it, when he claims that Gerdt Breker acted in justified self-defense after being hit twice by his captain:

„[…] myn principal Gerth Breker, Cordt Hemelink seligen, andere nargen den up de hantspiken geslagen, de slach uppe de fynger unde arm gegleden, unde dat de schypper vorhen mynen principal twe slege myth der hantspiken gegeven, dat he dar van gestortet.“

(Letter of Dirick von Minden 1. 2. 1559).

„Deweile dan nhun, auß den ergangenen gezeugnisse, kuntlich und offenbar, daß saliger Corth Hemelinges, von Gerth Breker meinen principalen, nicht doitlich vorwunt gewest, sonder alleine mein principal ex necessaria sui corporis defensione, des vorstorbenen frevel mit einem hantspikenn, auff die vinger unnd arm schlagende geweret …“

(Letter of Dirick von Minden and 15. 1. 1560).

Assuming we would have been medical experts in the court case against Gerdt Breker, we would like to suggest, der hochehrbare und hochweise Rath der Stadt Bremen should follow the plea of the advocacy of not guilty and absolve Gerdt Breker of all accusations related to the death of Cordt Hemeling, reducing the accusation at least to bodily injury maximally.

The technical details given in the documents also allow for some interesting glimpses about the construction of the ship, which are of interest for research upon historical ship building. We will dive deeper into these matters in a separate blog article.

References:

• Ballantyne, John H. & Smith, Brian (1999): Shetland Documents, volume 1, 1195 -1579, Lerwick

• Holterman (2016): Manslaughter in the north? the death of Cordt Hemeling on Shetland, 1557

• Holterman, Bart (2020): The Fish Lands. German trade with Iceland, Shetland and the Faroe Islands in the late 15th and 16th century, Berlin

• Holterman, Bart & Nicholls, John H. (2018): HANSdoc Database, Bremerhaven

HansDoc IDs 15570900SHE00, 15580207BRE00, 15580214BRE00, 15580307BRE00, 15580321BRE00, 15580502BRE00, 15590109BRE00, 15590201BRE00, 15590906BRA00, 15591212BRE00, 15600115BRE00, 15600129BRE00, 15600212BRE00

All documents Staatsarchiv Bremen, 2-r.11.kk., Akten der Hitlandfahrer

• Jahnke, Carsten & Graßmann, Antjekathrin (2003): Seerecht im Hanseraum des 15. Jahrhunderts. Edition und Kommentar zum Flandrischen Copiar Nr. 9, Veröffentlichungen zur Geschichte der Hansestadt Lübeck Reihe B 36, Lübeck

• One of the documents from the court case will be shown in the exhibition “Immer Weiter – die Hanse im Nordatlantik” in the German Maritime Museum in Bremerhaven, from 24 March 2023.

Wrong place, wrong time: the theft of Gerdt Hemeling’s ship on Shetland, 1567

Bart Holterman, 28 September 2016

Sumburgh Head (Sweineburgkhaupt), the southern tip of Mainland, close to which the harbour must have been which was used by Gerdt Hemeling. Image: Wikimedia Commons

In the early months of 1568, Bremen merchant Gerdt Hemeling (the brother of the deceased Cordt Hemeling, about whose death we wrote in an earlier blogpost) complained to king Frederick II of Denmark about the theft of his ship in Shetland by a “Scottish man”. This man had promised to return his ship, or to compensate him for it, but was taken captive by Danish officials and was now in prison in the castle of Bergenhus in Bergen, Norway. Now Hemeling, a “poor and extremely desperate man”, appealed to the Danish king to compensate him for the loss of his ship and his goods, which had been thrown overboard when the ship was taken, and most of which he had to leave on the shores of Shetland.

Gerdt Hemeling had traded peacefully for years between Bremen and Shetland, staying on the islands every summer to trade commodities from mainland Europe for fish. In the summer of 1567, however, this happened to be just the wrong time and place. While he was loading his ship the Pellicaen with fish in the harbour of “Ness in Schweineburgkhaupt” (probably Dunrossness near Sumburgh head, the southern tip of Shetland Mainland), a ship appeared from Scotland with a few hundred men on board, who offered Hemeling to buy his ship or to rent it for two months. Hemeling claimed to have had no choice but to accept this offer. The men from Scotland threw all merchandise on the shore and left, never to be seen again.

Gerdt Hemeling’s case was in itself not unique. Piracy on German merchants on Shetland occured more often, especially in these years. In the previous year (1566) the Shetland merchants from Bremen filed an official complaint to the city council in which they stated that at least six of them had become the victims of robbery. Scottish pirates had attacked their ships and trading booths and stolen their merchandise, money, weapons, and sailing instruments, to a calculated total damage of 1008 thaler. Two of the pirates’ captains, James Edmistoun and John Blacader, were arrested and executed the next year by the Scottish authorities.

Gerdt Hemeling, however, found himself in a much more complicated situation. The “Scottish man” turned out to be none other than James Hepburn, 4th earl of Bothwell, an opportunistic nobleman who played a rather controversial role in high politics of his time. In 1567, when Hemeling accidentally met him, Bothwell was a man on the run. He was suspected of having murdered the second husband of Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, of having kidnapped her (possibly with her own consent), and subsequently married her. Among the Scottish nobility, tensions with the catholic queen had risen in previous years, among others about religious matters, and Mary’s marriage to the protestant alleged murderer of her previous husband proved to be the limit. A coalition of nobles revolted, and faced Mary’s army in the battle of Carberry Hill. Mary eventually surrendered and was imprisoned, finally leading to her abdication, but Bothwell fled and tried to leave Scotland by ship to Shetland.

Bergenhus castle, Bergen, Norway. The so-called Rosenkrantz tower was constructed in the 1560s by Erik Rosenkrantz. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

However, Bothwell was being followed by two Scottish lords who controlled the navy. In these chaotic circumstances, Bothwell lost one of his ships which struck an underwater rock, and desperately tried to acquire more ships for his fleet in Shetland. Luckily for him, every year there were a few German trading ships in Shetland, and thus he took Gerdt Hemeling’s ship and another one from Hamburg. However, he was not able to get rid of his persecutors, and a battle resulted in which the mast of one of the ships broke.

A storm subsequently forced Bothwell’s fleet to sail towards Norway, where he was first held for a pirate, taken captive, and locked up in Bergenhus castle by Erik Rosenkrantz, the governer of Bergenhus. When his true identity became known, Frederick II realised the potential of Bothwell in Danish captivity as a pawn when dealing with the English and Scottish crown, and had him transported to Denmark. Bothwell (who had been made duke of Orkney and Shetland by Queen Mary) promised to return these insular groups (which Christian I of Denmark and Norway had lost to Scotland in 1469 as a pawn for the dowry of his daughter to the Scottish king, which he had been unable to pay) to Denmark if the king helped him to free Mary. The Danish king never made use of this offer: Bothwell was locked up in Dragsholm castle, where he would eventually die in 1578.

And did Hemeling ever get his ship back? Frederick II was unwilling to help Hemeling directly, but stated to him twice that he could press charges against Bothwell in Denmark if he wanted to. There are no sources pertaining to a case of Hemeling against Bothwell, so it is likely that Hemeling realised that a lawsuit in Denmark in such a complicated situation would not be worth the trouble, and he must have accepted his loss.

Manslaughter in the north? the death of Cordt Hemeling on Shetland, 1557

Bart Holterman, 29 January 2016

On a morning in August, 1557, Cordt Hemeling was found dead in his bunk. He was the skipper of a Bremen merchant ship lying at Whalsay in Shetland. The previous evening, Cordt had complained that he was not feeling well and had gone to bed early. After having been found dead the next morning, fingers soon pointed in the direction of two of Cordt’s crew members, Alert Wilckens and the carpenter Gerdt Breker, who as a consequence were accused of manslaughter. Alert and Gerdt, fearing persecution, abandoned ship and fled onto the island where they hid in the wilderness to escape from Cordt’s brother Gerdt Hemeling and the other crew members. As the vegetation on the islands is neither tasty nor very fit for human consumption they were soon starving. Alert was the first to give up, offerring to pay money as compensation and returned to the ship, by which all guilt was transferred to Gerdt Breker. Breker, in fear, tried to keep himself alive by eating the buds of shrubs, but starvation and the threat of being abandoned on the island and of losing his house in Bremen finally drove him back to the ship. He agreed to sign a confession of guilt, and promised to compensate Cordt Hemeling’s family, mortgaging his house.

We would not have known this story if Gerdt Breker had not tried to cancel the agreement upon return to Bremen, where he was expelled from the city. He started a law suit where he claimed to be not guilty of the death of Hemeling, and that he had been forced by his desperate situation to sign a confession against his will. The case and the resulting body of documents, which are still kept in the State Archives in Bremen, give us a unique insight into the life of the merchants and sailors during their stay on the islands, and the relations between them.

Tatort Shetland: the exact location of the fight between Gerdt Breker and Cordt Hemeling is unclear. Gerdt Breker claims that he returned from Laxfirth (Laeßfoerde; blue) with a boat when it happened. Olave Sinclair, the governor of Shetland, states that Hemeling’s ship was lying near Whalsay (red). Both harbours are well-known hanseatic trading sites (map copyright M. Gardiner and N. Mehler).

So what had happened that led Gerdt Breker to be accused of Cordt Hemeling’s death? Apparently there had been a tense situation between Hemeling and his crew for a long time, which erupted when a small boat manned by Alert Wilckens, Gerdt Breker and the helmsman was sent out to shore in Laxfirth to deliver some goods, stayed there longer than planned and returned to the merchant ship late at night. The skipper got angry at his crew members and hit them. Gerdt lost his patience and hit back, thereby breaking two of Cordt’s fingers, after which Alert also hit Cordt, causing him to fall down from the bridge onto the deck. (Note: according to hanseatic sea law, a skipper was allowed to hit his crew once as a disciplinary measure. Gerdt claimed to have been hit by Cordt twice, and was therefore at least theoretically allowed to hit back.)

Cordt, however, seemed to be alright after the fight. Apart from complaining about his fingers, he acted normally for more than a week and took part in the normal activities, including a couple of visits to the shore to fetch sheep, until his sudden death. The exact cause of his death remained unclear. Although Gerdt Breker argued that the injured hand would hardly have led to Cordt’s death, it was the only more or less plausible explanation accepted. Therefore, the Bremen city council did not plea him free from guilt altogether. The council did show some clemency, however. Gerdt could return to the city and his house, and the amount of money he had to pay as compensation to the Hemeling family was lowered.

We do not know what happened to Cordt Hemeling’s body, but it is likely that he was buried at a local church on one of the islands. It is known that other German merchants were buried on Shetland, such as the skipper Segebade Detken, who was also around with a ship when this story happened, and is listed as one of the witnesses in Gerdt Breker’s confession of guilt.

When sailing North, beware of swimming cows and Hamburgers. The Carta Marina and the North Atlantic

Bart Holterman, 5 October 2015

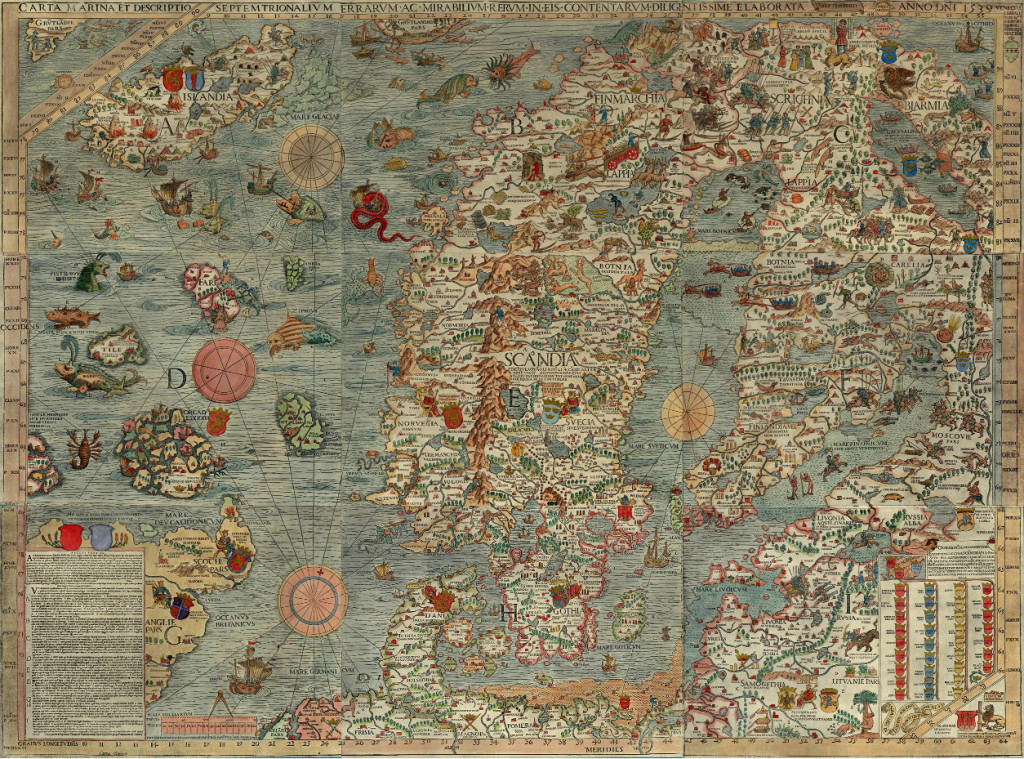

For the banner of this blog and our facebook page, we have displayed a section of the famous Carta Marina from 1539. On a first glance of the map, the many marvellous creatures that inhabit the land and the sea immediately catch the eye of the beholder, yet it also provides us with a good overview of the contemporary North Atlantic trade. Time to explore this remarkable document a bit further.

The map was made by Olaus Magnus (1490-1557), the brother of the last catholic bishop of Sweden. He had travelled Scandinavia and the lands around the Baltic Sea extensively before he was sent on a diplomatic mission to Rome by the Swedish king Gustav Vasa. He was never to return home. Dissatisfied by the Reformation in his homeland, Magnus stayed abroad, first in Lübeck and Danzig, later for a long time in Italy, soon joined by his expelled brother Johannes Magnus. In Italy he kept close contacts to learned men of his age, among others cartographers and travellers.

Under influence from these social circles, Magnus decided to transform his own knowledge about Northern Europe onto a map, which would appear in print in Venice in 1539. It was the first large-scale map of Scandinavia to be ever made, and had much influence on European cartography for the next decades. However, because of its high costs, the number of copies remained low. The map itself disappeared off the map of European learning, and was deemed to be lost since the late sixteenth century. Luckily in 1886 an intact copy of the map was discovered in the Bavarian State Library in Munich, and in 1961 another one, which now resides in Uppsala.

An explanation of the map appeared only in 1555 as Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus. In this book, Olaus Magnus described the geography, wildlife, and customs of the people of the North, illustrated with woodcuts. These woodcuts are clearly based on parts of the map, which includes many details about the people of the North, the political situation of the time, and the nature and wildlife. We can see kings sitting on their thrones, armies crossing the frozen Baltic Sea, people hunting seals, the most important towns and cities, lighthouses, whales attacking ships, enormous snakes, swimming cows and other sea monsters.

The map is divided into nine parts, marked A-I. It covers the entire Scandinavian peninsula, the Baltic, Northern Germany and the Netherlands, the entire North Sea and North Atlantic, including the coastline of Britain, the southern tip of Greenland and the mythical island Thule, known from classical geographical works. Of our interest are mainly the sections A and D, covering a large part of the North Atlantic.

Olaus Magnus probably never visited the North Atlantic himself. Instead, he had to rely on the stories and descriptions of others, for example the Northern German traders that told him about Iceland, the Shetlands and the Faroe Islands. Of the Shetlands and Faroes, Magnus must have had few information, as these archipelagos are only schematically drawn. One remarkable detail can be found on the Faroes, though, where we can see a whale being slaughtered on the shore, reminiscing a practice of hunting whales by driving them up the shore which is still practiced today.

For Iceland, Magnus was clearly better informed. The Carta Marina was the first map that drew the island in its more or less actual shape. Moreover, three vulcanoes attest to Magnus’s knowledge of the high vulcanic activity on the island. The two episcopal sees, Hólar (Holensis) and Skálholt (Scalholdin), are displayed, as well as the monastery Helgafell (Abbatia Helgfiall), which was famed for its butter production (butirum). The three knights on the eastern part of Iceland should probably be seen as an indication of Danish military presence on the island.

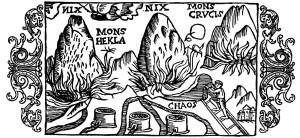

Three volcanoes on Iceland, from Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (1555), photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Better than the natural, religious, and political situation, the map attests of the economic situation. Firstly, the main export goods of Iceland are indicated. These are, besides the already mentioned butter: stockfish, sulphur, and falcons. Stockfish was dried cod, highly valued in Europe as a preservable source of protein, and the main trade good of the arctic region. It is shown on a pile on the south coast. Just north of it, three containers of sulphur are depicted. Iceland was one of the few places where pure sulphur could be found. Sulphur, being among others a key ingredient for making gunpowder, was a highly valued substance. Finally, a gyr falcon (falco albus) can be seen on one of the northern peninsulas of Iceland. Gyr falcons are only found in arctic regions, and due to its being the largest and strongest species of falcon, it was highly valued by the nobility for use in falconry.

Apart from the export goods, the realities of the north atlantic trade are displayed in considerable detail on the map. Various trading harbours are indicated, most notably Hafnarfjörður (Hanafiord), where merchants from Hamburg had built a church. We can see ships lying at anchor at these harbours, and three tents at Ostrabord, which probably indicate the temporary booths the merchants set up on the shore and where they displayed their goods on sale during the summer.

The most important countries and cities trading with the island are also indicated. We can see a ship from Bremen at anchor near Ostrabord, an English ship which confused a whale for an island, a ship from Lübeck being attacked by whales, and a Scottish ship under attack by one from Hamburg, indicating the dominance of Hamburg in the North Atlantic trade. It was no exception that competition between merchants from different places led to violent clashes, as in 1523, when the crews of ships from Bremen and Hamburg attacked an English ship in a conflict over the rightful ownership of an amount of stockfish, resulting in casualties among the English.

These elements make the Carta Marina a wonderful visual testimony of the North Atlantic trade in the sixteenth century.

Posted in: Sources