Immer Weiter – Fragen und Antworten, Teil 3: das Kogge-Special

Bart Holterman, 3 August 2023

(for English see below)

Obwohl sich die Ausstellung „Immer Weiter“ nicht mit dem Schiffswrack die „Bremer Kogge“ beschäftigt, gibt es viele Besuchende, die Fragen zu diesem Objekt gestellt haben. In diesem dritten Teil unserer Fragen und Anworten-Reihe haben wir diese Fragen gebündelt.

Wie viel ist die Bremer Kogge wert?

Der Wert des Schiffes als einzigartiges Kulturerbe ist nicht in Geld auszudrücken. Für die historische Forschung ist sie unersetzlich und liefert noch immer neue Einsichten.

Wann wurden Schiffe erfunden?

Das ist nicht genau zu sagen und unterscheidet sich für unterschiedliche Regionen auf der Welt. Bereits in der Steinzeit wurden einfache Wasserfahrzeuge aus ausgehöhlten Baumstämmen benutzt. Das waren sogenannte Einbäume. Ein solcher Einbaum wurde z.B. in Pesse in den Niederlanden gefunden und wird auf ein Alter von etwa 8.000 Jahren geschätzt. Später hat man dann angefangen, größere und kompliziertere Wasserfahrzeuge zu bauen. Zum Beispiel kennen wir archäologische Funde von größeren Booten aus England, die über 3.500 Jahre alt sind und mit Paddeln fortbewegt wurden (Dover-Boot). Das Mittelmeer befuhr man schon vor über 3.300 Jahren mit größeren, gesegelten Schiffen (Uluburun Wrack) und die Ägypter kannten schon vor 4.500 Jahren große aus Holz gebaute Flussschiffen (Khufu Schiff).

Wird davon ausgegangen, dass bei der Bergung der Bremer Kogge alle Überreste geborgen wurden?

Obwohl man den Boden bei der Bergung intensiv abgesucht hat, ist es anzunehmen, dass nicht alles, was erhalten war, auch gefunden wurde. Das Schiff lag viele hunderte Jahre in einem Fluß, so können Teile an andere Orte stromabwärts verlagert worden sein, wo sie möglicherweise immer noch liegen.

Wie viele Schiffe werden im Jahr gefunden?

Das ist sehr unterschiedlich, es ist schließlich vom Zufall abhängig. Aber es werden durch Bauarbeiten in (ehemaligen) Hafenbereichen und in Flachwasser- und Offshoregebieten immer häufiger Schiffswracks und Teile von Schiffen gefunden.

Warum hat man die Kogge nicht vor 1962 gefunden?

Die Kogge war Jahrhundertelang im Sediment im Flussbett der Weser vergraben und wurde erst bei Baggerarbeiten für eine geplante Erweiterung des Bremer Hafens gefunden. Hätte man diese Pläne nicht gehabt, wäre die Kogge wohl nie oder erst viel später entdeckt worden.

Wie wurde das Schiff aus der Weser geholt?

Taucher haben das Schiff in Einzelteilen aus dem Flussbett geborgen; diese wurden später im Museum wieder zu einem Schiff zusammengebaut und konserviert.

Könnte man unter Wasser ein Schiff erkunden?

Ja, das geht sogar ohne zu tauchen: Mit einem Echolot oder einem Magnetometer ist es möglich, von einem Schiff aus Objekte unter Wasser zu finden und zu identifizieren. Mit einem Sedimentsonar kann man sogar Strukturen im Boden erkennen. Um ein genaueres Bild zu bekommen müssen Forschungstaucher dann allerdings unter Wasser eine archäologische Begutachtung oder sogar eine Grabung durchführen.

In wie viele Werften ist die Kogge eingelaufen?

Die Kogge war in ihrem Leben wahrscheinlich nur auf einer Werft, und zwar auf der, wo sie auch gebaut wurde. Es wird davon ausgegangen, dass das Schiff sich noch im Bau befand, als es gesunken ist, und deswegen auch nie als Handelsschiff über die Meere fuhr.

Wie viele Schiffswracks werden wir neben der Kogge noch finden? Werden diese hier anzusehen sein?

Das ist unmöglich zu sagen, aber sicher werden es noch einige sein. Auf dem Meeresboden liegen tausende Wracks verstreut, wovon die meisten noch nicht genau untersucht wurden. Bei Bauarbeiten in Hafenbereichen sind in den letzten Jahren zudem viele Schiffsreste gefunden worden, von denen einige jenen der Bremer Kogge ähnlich sind. Manche davon werden bestimmt in Museen zu sehen sein. Die Bergung, Konservierung und Präsentation eines Schiffswracks ist aber kompliziert, sehr kostspielig und beansprucht viel Platz, weswegen sie wahrscheinlich nur in Ausnahmefällen stattfinden wird.

War die Bremer Kogge ein Kriegsschiff?

Nein. Zwar wurden Handelsschiffe im Mittelalter oft zu Kriegszwecken genutzt und auch ausgerüstet, aber es gibt keine Hinweise dafür, dass dies auch bei der Bremer Kogge der Fall war.

English version

Although the exhibition „Immer Weiter“ is not concerned with the shipwreck known as the “Bremen Cog“, many visitors have left questions about the ship on our Q&A station. In this blogpost, we have bundled questions about the cog and maritime archaeology.

How much is the Bremen Cog worth?

The value of the ship as unique cultural heritage is priceless. For our understanding of history she is irreplaceable and continues to provide new insights.

When were ships invented?

It is not possible to give an exact answer and differs for different regions of the world. Already in the Stone Age simple vessels were used which were made from hollowed-out trees. These are known as dugout canoes. Such a dugout canoe was for example found in Pesse in the Netherlands, which is believed to be about 8,000 years old. Later people started to build larger and more complex vessels. For example there are archaeological finds of larger vessels from England, which were rowed with paddles (Dover Boat). On the Mediterranean larger sailing vessels were used as early as 3,300 years ago (Uluburun wreck) and the ancient Egyptians had large wooden river barges 4,500 years ago (Khufu ship).

Is it assumed that all remains of the Bremen cog have been salvaged?

Although the river bed has been meticulously searched when the ship was salvaged, it is likely that not all parts of the ship that were preserved have also been found. The ship was located in a river for many hundreds of years, so it is possible that parts were drifted further downstream, where they might still be waiting to be found.

How many ships are found each year?

This differs a lot per year, as it primarily depends on coincidence. However, due to construction works in (former) harbour areas and in shallow water and offshore areas, shipwrecks and parts of ships are being found in increasing numbers.

Why was the Cog not found before 1962?

The Cog was buried in the sediment of the river bed of the Weser for centuries and was only found during dredging works for a planned extension of the harbour of Bremen. The Cog would never have been found, had these plans not existed, or at least only much later.

How was the ship retrieved from the Weser?

Divers salvaged the ship from the river bed piece for piece; later these pieces were reassembled as a ship in the museum and conserved.

Is it possible to explore a ship under water?

Yes, even without diving: with a multibeam or sidescan sonar or magnetometer it is possible to find and identify objects under water from a ship. With a sub-bottom profiler it is even possible to recognise structures in the sediment. However, to get a better picture it is neccesary for divers to perform an archaeological survey or even an excavation under water.

How many shipyards did the Cog visit?

During her life the Cog was probably only on one shipyard: the one on which she was also built. It is assumed that the ship was still in the process of being built when she sank, and never sailed the seas as a cargo ship.

How many shipwrecks we will still find next to the Cog? Will these be shown here?

That is impossible to say, but certainly many ships will still be found in the future. There are thousands of wrecks scattered on the sea floor, of which most have not been explored in detail. Construction works in harbour areas have revealed many remains of ships, some of which are similar to the Bremen Cog. Some of them will certainly be displayed in museums. However, because the recovery, conservation and display of a ship wreck is complicated, very expensive and requires a lot of space, this will occur probably only in exceptional cases.

Was the Bremen Cog a warship?

No. Although it happened regularly in the Middle Ages that cargo ships were used and fitted out for military purposes, there are no indications that this was the case with the Bremen Cog.

Posted in: Exhibition, General

Where have all the ships gone? The absence of German shipwrecks in Iceland

Bart Holterman, 22 December 2017

Mike Belasus, with Kevin Martin and Bart Holterman

Detail from Olaus Magnus Carta Marina 1539: The ship-destroying sea monster is symbolising the perils of a journey across the open ocean.

A Project on the Low German merchants’ trade from Bremen and Hamburg with the North Atlantic islands is not complete without the vessels that made trade across the ocean possible. The written sources tell us that many German ships were lost along the coast of Iceland, but until today, not a single mentioned shipwreck was found. This is not surprising, given the circumstance that underwater archaeology in Iceland is not even twenty years old.

Some facts about finding shipwrecks

The saying “Searching for a needle in a haystack” is fitting pretty well to the search for shipwrecks mentioned in historical documents, considering the abilities to determine a ship’s position in the past and the fact that 71 % of Earth’s surface is covered by water. Even today, many ships vanish without a trace. On top of that, the number of archaeologists looking for certain shipwrecks is extremely low. Therefore, most shipwrecks are found by accident and they remain more or less anonymous.

However, technology has improved and the potential for finding shipwrecks is much higher today than in the past. A number of devices can be used and combined for surveying the sea floor. A common combination is a side-scan sonar and a number of magnetometers, but this is still no guarantee for finding wrecks. When a ship is too decayed, or has settled into the sediment, the sound-rays of the side-scan sonar will not be able to produce a recognisable image. Moreover, magnetometers will not detect anomalies from the earth’s magnetic field when there is not enough metal on board the ship. Especially for medieval ships and early modern merchant vessels without guns, this can easily be the case. A sediment sonar could be a solution, which measures changes of density in the sediment with sound signals. The disadvantage is that waterlogged wood has the same density as waterlogged sediment. If a shipwreck has no denser cargo or ballast on board, the sonar will not detect density changes. Therefore such ships will remain hidden, even if an area is surveyed. Divers might be suggested as a final solution but a diver’s operating range is very limited, as he/she depends on depth, weather conditions, visibility and air supply.

The fact is that archaeologists rely in most cases on coincidences, which is how most of the known shipwrecks were found. The reason for this is that many other professions like builders, fishermen, geologists etc. spend much more time working on the sea floor than archaeologists, and sometimes stumble upon a wreck. One famous example for this is for example the “Bremen Cog” in the German Maritime Museum in Bremerhaven. A suction-excavator operator found it in the river Weser close to Bremen, when he was working on an extension of the riverbed. It became one of the most important finds in ship archaeology. Over the past decades, since underwater became an area of archaeological interest, hundreds of shipwrecks have been registered by the heritage departments of the German federal states but only a few of them could be identified by historical documents.

The author examining an anchor off the west coast of Gotland, at the site of the Visby-Disaster of 1566 (Photo: Jens Auer).

When we approach the shipwrecks from the historical documents, we have to realize that mentioned positions for lost ships are most of the time very vague. This situation can extend the search area dramatically without even knowing if the wrecks still exist as a coherent site. The conditions of the natural environment are vital to the survival of remains. Rugged coastlines, strong currents, micro-organisms, the chemical consistence of the water and the like can severely contribute to the decay of organic matter, metals and even certain types of stone. In the Mediterranean Sea, for example, ship hulls will not survive for a long time above the sea floor due to temperature, salinity and micro-organisms. Iron will soon vanish by the reaction with salt and oxygen and even marble and copper-alloys will decay. The opposite situation can be found in the Northern Baltic or the Sea Black Sea, for example. The Northern Baltic is deep, has a very low salt content and is cold. This prevents wood-decaying organisms to multiply and destruction from anchors or looting divers. The Black Sea water, on the other hand, has hardly any oxygen in a certain depth, which almost freezes time on the sea floor.

In addition, the circumstances of the sinking in connection to the natural environment play an important role. A German ship in Spanish service in 1588, the Gran Grifon, hardly left any structural remains. Another extreme example is the destruction of a united navy fleet of Lübeck and Danish ships during the Nordic Seven Years War on the west coast of Gotland in 1566. Out of thirty-seven ships, fifteen were lost and 6000 to 8000 sailors lost their lives in the so-called Visby-Disaster. Intensive archaeological diving surveys for several years could not reveal any wreck site. The ships literally vanished, most likely because they disintegrated in the storm on the rough sea floor and their remains were thrown up on the beach.

These examples shows us that a sunken ship mentioned in the historical documents does not always leave a proper wreck site. Sometimes scattered debris spread over square kilometres of sea floor can be all that is left of a ship.

The missing wrecks of Iceland

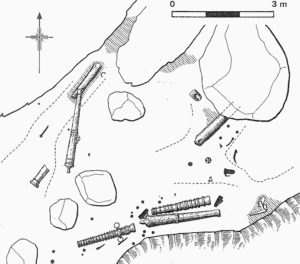

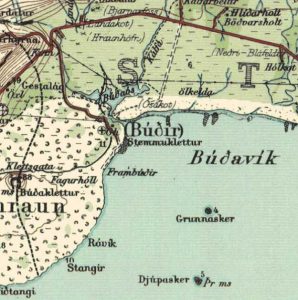

The site of the Bremen trading harbour Búðir/Bodenstede on the west coast of Iceland. It continued to be used by the Danes after 1601.

In theory, Iceland has a high potential for finding shipwrecks. Since the late 9th century, humans settle here and they had no other way than to cross the rough North Atlantic Ocean and make landfall on a rugged coast. Many ships, Norwegian, Danish, English, Low German and Dutch, evidently got lost on their route between continental Europe and Iceland. A considerable number of these found their end on the coast of Iceland, as we can read in the historical documents. Ragnar Edvardson has calculated a number of about 450 shipwrecks in Iceland, from the period from 1100 to 1900, most of which foundered on the West coast. Until today, no wreck from the period of the Low German trade has been found. The oldest ship found in Iceland is currently a Dutch merchantman, which sank in the harbour at Flatey in Breiðafjörður in 1659, and is currently under investigation by Kevin Martin. The scarcity of known shipwrecks in Iceland is not necessarily because they vanished completely, but because maritime archaeology is a very young discipline in this country and started only with sporadic projects from 1993 onwards. The relatively few inhabitants of Iceland also reduce the possibility of coincidental discoveries of wrecks due to the lack of building activities.

Vive la Coïncidence!

However, coincidences happen – even in Iceland. In 1998, an excavator hit timbers while digging a cable trench near Búðir on the Snæfellsnes peninsula in Western Iceland. They turned out to be fragments of a ship that was buried under the sand of an estuary. Some timbers and ballast stones were recovered by archaeologist Björn Stefánsson, and brought to the National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavik, were they were documented and put in storage. None of the recovered timbers was suitable for dendrochronological dating, but the ballast included stones that can possibly originate in Norway, Britain or Greenland. However, this does not give any indication were the ship was coming from, because ballast was taken from board and loaded in all harbours depending on the cargo and to adjust the angle of the ship in the water, to trim the ship. The recovered timbers give the impression of an old carvel-built ship. The material seems not to be of the finest quality, but this is hard to judge from only a handful of timbers. A promising fact is that Búðir was an important trading centre in Iceland for at least 200 years. It was already visited by Bremen merchants in the late 16th century, who called it “Bodenstede”. For a long time it was the main trading site for the Snæfellsness Peninsula, called first by cargo ships of the Low German merchants and later by Danish and Dutch ships. It was abandoned as a trading post in 1787.

The recovered ship timbers from Búðir today at the National Museum of Iceland, Reykjavik (Photo: Kevin Martin)

For this reason, we have written sources on the activities on this site including the loss of several ships during these 200 years. The problem for the identification of the accidental found ship is the fact that there was not only one ship lost near the site. We know at least about eleven ships that are reported to have been lost at Búðir and its harbour Búðavik. Of those eleven ships, one was from Bremen. It belonged to the merchant Vasmer Bake and sank in or close to the harbour of Bodenstede in 1587. This was reported by Carsten Bake, his son, who himself was involved in the Iceland trade. In 1607, a Danish ship wrecked at Búðir. For 1666, another ship sank west of Búðir. More ships sank in this area in 1724, 1728 (Danish) and 1754, and lastly, Bjarni Sívertsen’s cutter, which got lost here in 1812.

Certainly, it is possible that the ship found in 1998 is Vasmer Bake’s lost vessel from 1587, but the timbers cannot give us any more detailed information. All we can say today about the few recovered timbers is that there are five floor timbers and two fragments with an unknown function. The floor timbers indicate that the cable trench hit the wreck most likely in the bow section, leaving most of the buried remains uncovered. Each plank was attached to each frame with at least two tree nails, and each frame was connected to the keel with one or two tree nails. The dimensions of the floor timbers vary a lot, from flat and wide to high and narrow. This might be an indication that whoever built the ship faced either a shortage of crooked compass timbers, or the building did not rely on an even framing in a shell based building method, or both. However, it can also not be excluded that we face the remains of Bjarni Sívertsen’s cutter from 1812. Only future investigations might give us an answer.

References:

Edvardson R. and Grassel Ph., The Potential of Underwater Archaeology in the North Atlantic. In: N. Mehler, Travelling to Shetland, Faroe and Iceland during the 15th to 17th centuries (in press).

Stefànson, B., Skipsviðir úr Búðaósi. Rannsóknaskýrslur fornleifadeildar 1998. Fornleifadeild þjóðminjasafns Íslands, Reykjavik 1998

Posted in: General, Reports, Stories

El Gran Grífon – The story of a Hanseatic ship in the Spanish Armada, wrecked in Shetland

Philipp Grassel, 29 June 2017

In the 15th to 17th centuries, the North Atlantic Islands of Shetland, Faroe and Iceland were frequently visited by Hanseatic merchants, who usually made one voyage each year. The trading season started roughly in April and finished in August/September and because of its regular character, we have much information about the number of Hanseatic ships sailing North each year.

Map of the Shetland Islands with the positions of Hanseatic ship losses. Fair Isle and the wreck of the Gran Grífon can be seen in the smaller map (map created by P. Grassel)

In the middle of the 16th century, on average 5 ships per year from Bremen and 1 or 2 ships from Hamburg travelled to Shetland. Contemporary sources from 1560 speak of a minimum of 7 ships from Bremen and Hamburg in Shetland harbours. In Iceland, the numbers were even higher. For example in 1585, 14 ships from Hamburg alone and 8 ships from Bremen, Lübeck and Danzig reached Icelandic harbours, and in 1591 as many as 21 ships from Hamburg arrived in Iceland. In spite of these high numbers of voyages and some documented losses of Hanseatic ships – there are at least 10 known losses around Shetland and 3 losses around Iceland – no wrecks or remains of Hanseatic trading ships in the North Atlantic were found yet.

However, this does not mean that there are no Hanseatic trading vessels to be found in the North Atlantic at all. The only wreck which could be considered as Hanseatic are the remains of the El Gran Grífon (The great Griffin). This ship, which is the oldest known wreck both in Shetland and of all the North Atlantic islands, has a quite unusual history.

As the name already suggests, the Gran Grífon did not end up in Shetland by merchants from Bremen or Hamburg. Instead it was part of the famous Spanish Armada. This was a Spanish fleet which was sent in 1588 by the Spanish King Philipp II to invade England. The operation was a complete failure; the bulk of the fleet was lost after attacks by the English Navy and subsequent bad weather conditions on the North Sea.

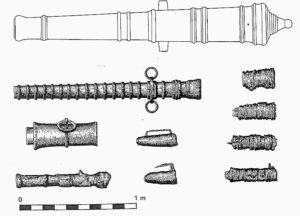

The Gran Grífon itself was a former Hanseatic merchant vessel from Rostock, a Hansa Town in the Baltic Sea, and was bought by the Spanish Navy for the Armada. This was not unusual; merchant ships were in this time often converted for military use in times of war. After the ship had been roughly modified, it was used as the flagship for a squadron of 23 supply and troop ships. These poorly armed squadrons, called urca squadrons, consisted of acquired merchant vessels and were commanded by Juan Gomez de Medina. The ship had a tonnage of 650 tons, a length of around 30 m and an armament of 38 unspecified cannons. The original crew of 43 men were supplemented with around 200 soldiers. So all in all carried the ship over 243 men.

After some battles with the English Navy, which took the lives of over 40 soldiers and seamen, the ship was driven to the North of the British Isles. It was accompanied by other Armada vessels like the Barca de Amburgo (probably another converted Hanseatic ship from Hamburg), Castillo Negro and La Trinidad Valencera. After the Barca de Amburgo sank, the Gran Grífon and the Trinidad Valencera took over the surviving men.

Shortly afterwards the contact between the ships was lost and the Gran Grífon sailed in a South-West direction, trying to get back to Spain through the Atlantic. However, after the ship reached the latitude of the Galway Bay in Western Ireland, a strong gale from the South-West got up and flouted the Ship back North. Since the ship was heavily damaged, Juan Gomez de Medina decided to search for the nearest possible land. This turned out to be Fair Isle, the most southern and remote island of the Shetland archipelago. The ship tried to anchor in vain before it was driven ashore and ended up on a cliff at Stroms Hellier at the Southeastern end of the island in September 1588. Most of the remaining crew members and soldiers, including Gomez de Medina, managed to escape from the ship before it disappeared in the waves.

For a long time, the wreck remained untouched in the 9-18m deep water. In 1728, W. Irvine salvaged three cannons from the wreck. An archaeological excavation was carried out between 1970 and 1977 by the Institute of Maritime Archaeology of St Andrews University, led by C. Martin. Unfortunately the wreck was barely preserved. Parts of the stern, a rudder pintle, cannons of different sizes, coins, cannon balls, musket bullets and lead ingots were found, recorded and removed. Other, smaller finds like the handle of a pewter or “Hanseatic” flagon, as well as a curved iron blade, were also recovered. The wooden part of the stern was preserved under a boulder, which had tumbled down from the nearby cliff. Most of the finds were brought to Lerwick, where they can be partly seen at the Shetland Museum.

Further reading:

K. Friedland, Der hansische Shetlandhandel, in: K. Friedland, Stadt und Land in der Geschichte des Ostseeraums (Lübeck 1973) 66-79.

C. Martin, Cave of the Tide Race – El Gran Grifon, 1588, in: C. Martin, Scotland’s Historic Shipwrecks (London 1998) 28-45.

P. Grassel, Late Hanseatic seafaring from Hamburg and Bremen to the North Atlantic Islands. With a marine archaeological excursus in the Shetland Islands, Skyllis. Zeitschrift für marine und limnische Archäologie und Kulturgeschichte, 15.2, 2015, 172-182.