Fish and Ships continues: new project about the international trade of Orkney and Shetland in the early modern period

Natascha Mehler, 27 March 2020

Over the past years, our research on the German trade with the North Atlantic islands has mainly focused on the exchange with Iceland. In the case of Shetland, however, much written and archaeological material exists which is of great potential to help uns understand the operation of international trade on the North Atlantic island. We therefore, we applied for a new grant in order to continue our work with Shetland. The project also addresses the question whether Orkney, which shares many characteristics with the other islands but hardly ever appears in the written sources, was also visited by German merchants in search of dried fish and if they did, to what extent and how this trade was organised. Finally, we will broaden our view to include other international (English, Dutch, Norwegian) traders in the area.

We are happy to announce that our team, together with other archaeologists and historians from the University of the Highlands and Islands Archaeology Institute and the University of Lincoln have been awarded a grant of c. 900.000 Euros from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the German Research Foundation (DFG) to do this. Over the next three years, the members of the project “Looking in from the edge (LIFTE)” will look at a number of early modern documents, objects from archaeological excavations and also conduct fieldwork in Orkney and Shetland. This also means that we will continue blogging on Fish and Ships for more stories and short research reports about pre-modern trade in the North Atlantic. Stay tuned!

Here are the links to our announcements in English and in German, with further information.

https://www.dsm.museum/pressebereich/der-lange-arm-der-hanse/

Posted in: Announcements, General

Keeping the Faroese bishop warm – how a tiled stove tells the story of the Reformation in the Faroes

Natascha Mehler, 16 August 2017

with Torbjörn Brorsson, Martina Wegner and Símun V. Arge

In 1557 the Reformation in the Faroes came to an end when the Faroese bishopric at Kirkjubøur was abolished and its properties confiscated by Christian III of Denmark. This was the result of a process which started in 1539 when Amund Olafson, the last Catholic bishop, was replaced by Jens Gregersen Riber, the first Lutheran bishop of the Faroes. Jens Riber stayed at Kirkjubøur until 1557 when he left to take on a new position in Stavanger. We know very little about the lives of these two bishops. However, during archaeological excavations conducted in 1955 at the site of the former episcopal residence, the remains of a tiled stove dating to the early and mid-16th century came to light which add knowledge about the daily life at Kirkjubøur.

The tile fragments were now, more than 60 years after their discovery, analyzed as part of this research project. Tiled stoves were a luxurious rarity in the North Atlantic islands. In Iceland, for example, 16th-century tiled stoves are only known from the two bishoprics at Skálholt and Hólar, the Danish residence at Bessastaðir and from the monastery at Viðey. The Kirkjubøur fragments are the only remains of a tiled stove in the Faroes. In Denmark or Northern Germany, however, tiled stoves were rather common in burgher households and those of the nobility.

19 stove tile fragments were found at Kirkjubøur, all made from red clays, moulded with relief decoration and applied with a white slip and green lead glaze. Varying fabric and decoration indicates that the tiles are the products from at least two different workshops. This means that either the tiles of the former stove were exchanged during its lifetime, or the stove was made from tiles from different workshops. The latter interpretation would be rather unusual in a continental context but all known early modern tiled stoves from Iceland were made of tiles from different workshops because access, import and maintenance were very difficult.

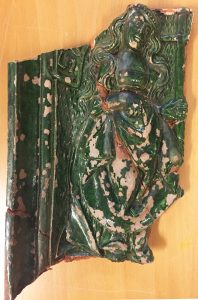

Stove tile made near Lübeck, with the remains of Judith and the head of Holofernes (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

The images on the Kirkjubøur tiles mirror the struggles of the introduction of the Reformation in the Faroes. All tiles show Christian or biblical motifs and themes, but while one of the identified motifs displays catholic imagery, others are clearly reformist in meaning. In many Northern European households such stove tiles decorated with Lutheran imagery were indeed used as a medium to express the Lutheran confession.

Stove tile produced in the area between Lübeck and Bremen, with the relief of probably a female Saint (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

One stove tile fragment shows a female figure with a cross in her left hand. A letter “S” is preserved, suggesting that this is a female saint such as Helena. If this interpretation holds true it would be a tile with purely Catholic imagery. The best preserved stove tile shows a bearded man in profile and the words [S]ANT PAVLO APOSTOLVS. Although this is a depiction of yet another saint – and thus rather Catholic in meaning – the letters of Paul the Apostle were often invoked by reformist theologians of Wittenberg. All other identified motifs were popular amongst supporters of Lutheranism. One fragment shows the lower body part of a female figure with a man’s head next to it. This is clearly a depiction of Judith with the head of Holofernes in her hand, a widespread stove tile motif in Lutheran contexts. And two identical tiles show the ascension of Jesus and parts of the creed of the Lutheran catechism. The surviving text reads 6 ER IST AVGEFARE[N] GEN HIMEL SITZET ZVR RECHTEN GOTES DES ALMECHTIGEN VATERS (transl. “he has ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of the Father”). The letter 6 indicates that this is the sixth stove tile in a series.

Eight fragments of these stove tiles were selected for analysis by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MA/ES), a standard method in ceramic analysis, carried out by Torbjörn Brorsson (Kontoret för Keramiska Studier). The main goal of the analysis was to determine the chemical composition of the various fabrics, with the aim to identify the workshops which produced these tiles. The results show that the tile with Paul the Apostle was made in Lübeck, and the tile with Judith and Holofernes, as well as the tile with the creed of the Lutheran catechism, in the surroundings of Lübeck. The tile with the female saint was made in the area between Lübeck and Bremen, which also includes Hamburg. This is no surprise; Northern German potters were the leading craftsmen to supply the Northern European market with stove tiles at that time.

The stove tiles were imported to the Faroes during the period when the Faroes were licensed to Hamburg citizen Thomas Koppen, between 1529 and 1553. Thomas Koppen was Oberalter of the churches in Hamburg and therefore an important figure in the process of the Reformation there. Maybe Koppen’s merchants (very likely he never visited the Faroe Islands himself) had brought the tiles from Lübeck via Hamburg to the Faroes. It is also very likely that Norwegian merchants from Bergen brought the tiles to the Faroes. The islands were closely connected to Bergen, with many ships travelling between the harbours of Tórshavn and Bergen. Lübeck merchants held a very important position in Bergen at that time and the tiles could have been brought from Lübeck first to Bergen and then went further to the Faroes.

The story that the tile finds suggest is such: a tiled stove was first erected at Kirkjubøur during the office of the Catholic bishop Amund Olafson, and fitted with tiles such as the one with the female saint. When Jens Riber took over as first Lutheran bishop in 1539 he bought new tiles from a different workshop and exchanged the purely Catholic images on his stove with motifs of the new faith. Only then could he enjoy the comforting warmth effusing from his stove without being agonized by the troubling sight of Catholic images.

References:

Julia Hallenkamp-Lumpe, Das Bekenntnis am Kachelofen? Überlegungen zu den sogenannten “Reformationskacheln”. In: C. Jäggi and J. Staecker (eds.), Archäologie der Reformation. Studien zu den Auswirkungen des Konfessionswechsels in der materiellen Kultur (Berlin 2007) 239–258.

Louis Zachariasen, Føroyar sum rættarsamfelag 1535–1655 (Tórshavn 1961), see pages 161–184.

What did the German trading stations in Iceland look like?

Natascha Mehler, 27 April 2017

The Danish trading station at Grundarfjörður, as depicted in the 1790s. Before the Danes took over the trading post in the early 17th century it was in the hands of German merchants.

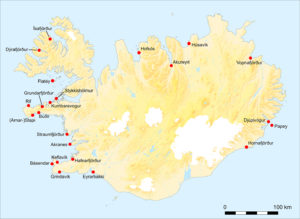

In the 16th century there were approximately 25 trading stations in Iceland which were regularly frequented by merchants from Bremen, Hamburg, Oldenburg or Lübeck. Most of these stations lay in the western part of the island, around the Snæfellsnes and Reykjanes peninsulas and in the Westfjords, because these were the areas where most fishing settlements were located and where cod, which was transformed into the main trading commodity stockfish, was abundant.

German trading stations in Iceland. Landey is near Kumbaravogur (map by Libby Mulqueeny, Mark Gardiner and Natascha Mehler).

It is difficult to tell what these German trading stations looked like because none have survived until today. In 1604, the Danish king Christian IV ordered to tear down all German buildings in Iceland, as a consequence of his imposition of the Danish trade monopoly (1602–1787). During the early 17th century many of the German trading stations (such as Grundarfjörður in the image above) were taken over by Danish traders and subsequently developed into permanent and more substantial settlements, many of which still exist today. What we don’t know is whether the Danish traders really tore down the German buildings, as was the will of the king, or simply re-used the buildings and infrastructure. The latter would certainly have been more practical in a country where building material was scarce.

Luckily, a handful of German trading sites did not develop into modern settlements and remains have survived until today. One of them is situated on the small tidal island of Landey at the northern side of the Snæfellsnes peninsula, near the present farm of Bjarnarhöfn. Written sources mention a trading post visited by merchants from Oldenburg and Bremen in the 1590s, but the amount of information from the surviving documents is very low. In 1593, Carsten Bake from Bremen acquired a three-years license for the harbour, and afterwards the harbour was given to the count of Oldenburg. In 1599, a request by the count to renew the license for Landey was denied by the Danish king because it was already in use by someone else. Who this person was is not mentioned.

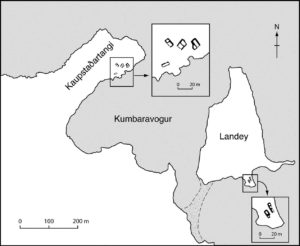

Ruins of German trading stations at Kaupstaðartangi and Landey (map by Mark Gardiner, Natascha Mehler and Libby Mulqueeny).

Today, Landey is a small island only used by sheep for grazing. The outlines of two buildings are clearly visible. They are situated on a small plain near a beach that was used as a landing site, to pull up small boats. The western side of the island faces a bay called Kumbaravogur, and on the other side of that bay lies Kaupstaðartangi, a headland where the remains of a trading station called Kummerwage have survived. This close proximity could be the reason why Landey started to be used as a trading post in the first place, as Kummerwage had been a harbour of Bremen merchants for a long time, but was given to Joachim Kolling from Oldenburg in 1580. Bremen tried hard to get the harbour back, but without success. The merchants of Bremen must have tricked the Danish king in requesting a license for the nearby Landey. When the king realised his mistake he included the clause that the license would go to Oldenburg after the Bremen one expired.

The ruins of two buildings at Landey (centre), on a green plain overlooking the landing site (image Natascha Mehler, 2016).

A trial excavation conducted with Fornleifastofnun Íslands at Landey in the summer of 2016 has shown that both buildings on Landey were indeed dwellings, although rather simple constructions. The walls were built in the Icelandic way, made of turf with stone linings. A fire place was discovered in the western building and no signs of furniture or other equipment were found. However, ten fragments of a ceramic cooking pot made of red earthenware were discovered. ICP-MS analysis of the sherds (conducted by Torbjörn Brorsson, KKS) has shown that the pot was made in Bremen, or in very close vicinity thereof (e.g. in Oldenburg).

The trial trench through the western building at Landey. The outlines of the building are clearly visible, as is the turf construction of the wall (image Vilmundur Pálmason, 2016).

The building to the east has two inner partition walls which indicates that it could have been used as a storage facility. Taking the scarce written and archaeological evidence together we can conclude that the buildings were indeed dwellings of some sort but only used for a very short time. This corresponds well with what we know about the Icelandic trading stations from other written sources: they were only used during the summers, when the foreign vessels were in Iceland, and their owners did not invest in solid infrastructure because they were not sure whether they would return the next summer. For Landey, records only exist for the 1590s.

Written sources indicate that merchants generally slept in the dwellings on land while the ship´s crew stayed on board. However, the excavations at Landey give food for thought. A Northern German merchant might have found it more comfortable to stay on board than to spend his nights in a damp and dark turf building…

References:

D. Kohl, Der oldenburg-isländische Handel im 16. Jahrhundert. Oldenburger Jahrbuch 13, 1905, 34–53.

Mehler & M. Gardiner, On the Verge of Colonialism: English and Hanseatic Trade in the North Atlantic Islands, in Peter Pope and Shannon Lewis-Simpson (eds.), Exploring Atlantic Transitions: Archaeologies of Permanence and Transience in New Found Lands. Society of Post-Medieval Archaeology Monograph 8 (Woodbrige 2013) 1-15.

Oldenburg, Niedersächsisches Landesarchiv, Best. 20, -25, no. 6.

Copenhagen, Rigsarkivet, Tyske Kancelli D 11, Pakke 28 (Island og Færøer, Supplement II, no. 25)

The cultural impact of German trade in the North Atlantic

Natascha Mehler, 19 October 2016

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the North Atlantic islands of Iceland, Shetland, and to some extent also Faroe, were closely tied to the cities of Bremen and Hamburg. Merchants from these hanseatic cities regularly travelled North to exchange goods such as grain / flour, beer, timber and tools for stockfish and sulphur. In the second half of the 16th century about 500 to 750 merchants, sailors, craftsmen, priests and others from Hamburg and Bremen spent their summers in Iceland. On the other hand, a considerable number of Icelanders used Hamburg and Bremen ships to travel to the continent, e.g. to be educated in jurisprudence or theology at the universities in Copenhagen, Rostock and Wittenberg. They brought back new knowledge that changed the insular societies.

The German presence on the islands and the stay of islanders in Northern Germany had a profound impact on the North Atlantic insular societies. Tracing this impact will be the main aim of an interdisciplinary research seminar that takes place from 26 to 28 October 2016 at the museum Schwedenspeicher in Stade near Hamburg. It is organized in cooperation with the archive Stade and the museum Schwedenspeicher Stade.

The main aim of this seminar is to trace and disentangle the forms of impact. The topics and questions we want to discuss during the seminar include:

- What role did the German connections play in the assertion of the reformation in Iceland, Shetland and Faroe? What was the position of the Danish and Scottish crown? How did religious life change on the island?

- What was the cultural effect of the reformation and how did the new scholarship change the insular societies? How did knowledge transfer happen?

- What role did hanseatic measurements (e.g. the Hamburg ell) and coinage (e.g. Reichsthaler) play on the islands and how were their values converted into the Icelandic, Faroese and Shetland value system? Did the different value systems effect the economic connections?

For more information on the seminar click here to download the flyer for the cultural-impact-research-seminar.

Posted in: Announcements

Worth a fortune: Icelandic gyrfalcons

Natascha Mehler, 11 August 2016

Throughout the medieval and early modern period, Icelandic gyrfalcons were highly valued at the courts of European rulers and they were worth a fortune. Indeed, Frederick II (1194-1250), Holy Roman Emperor, already noted in his treatise De arte venandi cum avibus that the best falcons for use in falconry were gyrfalcons (…et isti sunt meliores omnibus aliis, Girofalco enim dicitur). The reason for this was that of all falcon species, gyrfalcons (Falco rusticolus) are the largest and most powerful. Their plumage varies greatly from completely white to very dark, of which the white variety was the most valued hawking bird in the Middle Ages, and still is today. They only inhabit sub-arctic and arctic areas, with their highest population density in Iceland (one pair per 150-300 km²). During the breeding season (roughly February to June) there are today 200-400 nesting pairs in Iceland, and in the winter the population increases to 1.000-2.5000 individuals, due to migrating birds from Greenland.

Written sources from the 16th century, when German merchants from Hamburg and Bremen dominated the trade with the North Atlantic islands, give us a better insight into the falcon business with Iceland. Matthias Hoep, a Hamburg merchant, has left behind a collection of account books (1582-1594) which show us that he traded in many commodities such as fish, timber, and tools, and specialized in the trade of falcons. Hoep employed falcon catchers to catch birds in Iceland for him and he made specific contracts with them. The books record a great number of falcons and other birds of prey that he bought from falcon catchers and which he then sold on. On 5 April 1584, Hoep made a contract with the falcon catchers and brothers Augustin and Marcus Mumme which he commissioned to travel to Iceland to catch falcons. The contract specified the bird species, the conditions of the birds upon delivery, and the prices Hoep was going to pay after the successful return of the Mummes from Iceland:

“On 5 April [1584] I have dealt in my house with Augustin and Marcus Mumme, in the name of god, that they shall sail to Iceland in the name of god, and we agreed that I will give for each pair of falcons 11 ½ daler, and 2 tercel [male falcons] for 1 falcon, and what is blank shall be counted as a red [unmoulted] falcon. But what is white and moulted once, or moulted twice and beautiful, for those I shall give them 20 daler for each falcon and 10 daler for a tercel. But what has moulted three times we shall agree upon with good will, and if god and luck provides them with white falcons, I will give the one who catches them black cloth for a jacket of 2 ½ ells, all of this is validated with a denarius dei of 1 sosling each, and both brothers have promised with an oath to bring the best birds they can get and to take no birds away, neither in Iceland nor during the journey back, until they have all been delivered to me.“

Roughly five months later, in September 1584, the brothers returned from Iceland and handed over 49 birds to Matthias Hoep.

Detail of the Carta Marina (1539) showing the coat of arms of Iceland (stockfish), with a gyrfalcon (FALCO ALBI) above.

Later documents tell us how the shipping of the falcons was done. During the 17th century, a Danish falcon ship went to Iceland annually to transport falcons from Iceland to Copenhagen. The falcons were kept below the deck and sat on poles which were lined with vaðmál. During the journey, the birds were fed with meat of cattle, sheep or birds, dipped in milk, and when they were sick, they were fed with a mix of eggs and (fish) oil. Upon arrival of the birds in Hamburg, Mathias Hoep checked their health and quality and he considered them in good state after they had eaten three times and their feathers were not broken.

Most of the birds that Hoep received were sold to English merchants such as John Mysken who bought 55 birds of prey in 1584 and had them shipped to England, most likely to be sold to the English court. It is likely that Hoep also had good contacts with Icelanders, both in Iceland and in Hamburg. His professional network may have included Magnús Jónsson (c. 1530-1591), who had studied law in Hamburg, probably until 1556. In Iceland he became chieftain and sýslumaður (sheriff) at Þingeyjaþingssýsla and Ísafjarðarsýsla, districts in the North of Iceland with a very high density of falcons. No wonder his seal from the year 1557 shows a gyrfalcon in the centre.

Seal of Magnús Jónsson, dated 1557. The priest Ólafur Halldórsson, a contemporary of Magnús Jónsson, described the seal in a poem: „Færði hann í feldi blá, fálkann hvíta skildi á, hver mann af því hugsa má, hans muni ekki ættin smá.” (transl. „he carried in a blue field, a white falcon on his shield, so that everybody shall think his family is not insignificant“).

In the second half of the 16th century, king Frederick II of Denmark-Norway (1559-1588) started to regulate the export of falcons to foreign countries. From the 1560s onwards, foreign falcon catchers needed to buy a permission (Icel. fálkabréf, falcon letter) to catch falcons.

Were falcons also caught in Shetland or the Faroes?

We have not found any written evidence for that. The obvious reason for this is that there are not many falcons around in Shetland and the Faroes. Gyrfalcons only appear as vagrant birds, and peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) exist in Shetland only in small numbers. However, it is worth pointing out that in the years 1601 to 1606 one Tonnies Mumme is recorded to have sailed each summer from Hamburg to Shetland. We do not know whether this is the same Tonnies Mumme that is reported as falcon catcher in Iceland in previous years, or whether Tonnies is related to the Augustin and Marcus Mumme mentioned above, but it seems very likely. He may have tried his luck in Shetland, or might have changed his profession and have traded in other items.

Further reading

Natascha Mehler, Hans Christian Küchelmann & Bart Holterman, The export of gyrfalcons from Iceland during the 16th century: a boundless business in a proto-globalized world. In: Gersmann, Karl-Heinz & Grimm, Oliver (eds.): Raptor and human – falconry and bird symbolism throughout the millennia on a global scale, vol. 3, Advanced studies on the archaeology and history of hunting 1 (Neumünster 2018), 995-1019.

Kurt Piper, Der Greifvogelhandel des Hamburger Kaufmanns Matthias Hoep (1582-1594). Jahrbuch des Deutschen Falkenordens (2001/2002), 205-212.

Björn Þórðarson, Íslenzkir fálkar. Safn til sögu Íslands og íslenskra bókmennta (Reykjavík 1957).

Posted in: Stories