Till death do us part: Graves of sixteenth-century German merchants in the North Atlantic

Bart Holterman, 11 October 2018

When one has the chance to visit the northernmost island of Shetland, Unst, it is worth visiting the ruined church at Lunda Wick, in a bay to the Southwest of the isle. To get there, one has to take a small gravel road across a barren moory landscape where nothing seems to live but sheep and the occasional marsh bird. At the end of the path, one reaches a secluded bay where the grey waves and the rain torture the sands of the beach, and out of the fog a ruined medieval chapel appears with a graveyard around it. Inside the roofless chapel are a number of old tomb stones, the text made almost illegible by the lichen that overgrows them and centuries of rain and salty sea wind. In a corner lies a grave slab, on which it is possible to discern a text written in Low German, with great difficulty: “Here lies the honourable Segebad Detken, citizen and merchant from Bremen, who has traded in this country for 52 years, and died [in the year 1573], the 20th of August. God have mercy on his soul” (see below for the Low German text).

Segebad Detken is known from written sources about the Bremen trade with Shetland. He can be tracked from 1557 onwards as a skipper in the northern harbours Burravoe in Yell, and Baltasound and Uyeasound in Unst. In 1566, he was robbed by Scottish pirates in the harbour of Uyeasound. As his tomb slab mentions that he had been trading for 52 years in Shetland, he must have died in the late 16th century (see below). After his death, his relatives took over the business: among others his son Herman and grandson Magnus are recorded as merchants in northern Shetland in the early 17th century.

The grave slab of Segebad Detken in the ruined church in Lunda Wick. Photograph: Bart Holterman, 2018.

Given the long careers of German traders in the North Atlantic, and the fact that Bremen and Hamburg merchants dominated this trade for over 100 years (for Shetland even longer), it is not surprising that some of these merchants were buried on the islands when they died there. We can find another example just a bit outside the same church. There is another grave of a contemporary of Segebad Detken, that of his fellow citizen Hinrick Segelken. The Low German text on his slab translates as: “In the year 1585, the 25th of July, on St James’ day, the honourable and noble Hinrick Segelcken the Elder from Germany and citizen of the city of Bremen, died here in God our Lord, who has mercy on him.”

The tombstones were most probably imported by the German merchants, as the sandstone from which they were made is not available on the islands. By erecting a distinct grave marker for their deceased colleagues, they did not only honour their remembrance, but it also served to strengthen their ties with the local communities. The material and textual aspects of the monuments reminded the observer of the importance of the German merchants for the local economy, even across the boundaries of life and death.

A similar situation we find on Iceland, where we can also find tombstones of German merchants. The National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavik, for example, houses the tomb slab of Bremen merchant Claus Lude (follow link for an image), who was originally buried in the monastery Helgafell on the Snæfellsnes peninsula. The stone shows his house mark, a seal with two crossed stockfishes, and a text which mentions that he died on 3 June 1585. Lude is known to have been active in harbours in Snæfellsnes in the 1550s, and held a license for the harbour Grindavík in 1571.

In southern Iceland, at the graveyard of the former monastery Þykkvabær, one can still find the tombstone of Hans Berman the Younger from Hamburg, who died in 1583. The monastery records reveal that he was administrator of the monastic property (klausturhaldari) and was killed by the parish priest of Mýrar. His name also appears in the register of the Confraternity of St Anne of the Iceland merchants in Hamburg, where another Hans Berman (probably his father) was elderman around the same time.

In Hafnarfjörður near Reykjavík, the Hamburg merchants had their headquarters and also erected their own church. It is likely that they also had a graveyard where they buried their dead. During construction of the modern harbour of Hafnarfjörður in the 1940s, human bones were found which many believed to be from the old German graveyard in the town. It might even be possible that these bones once belonged to Hamburg merchant Hans Hambrock, the only death of a Hamburg merchant in Hafnarfjörður known from the written record. Hambrock had died from the injuries inflicted upon him by his colleague Hinrick Ratken, who drew his knife against him after Hambrock had hit Ratken on the head during a conflict about the unloading of a ship in 1599. Regrettably, the remains of the German church in Hafnarfjörður are now buried below the modern town.

Inscriptions on the discussed tombstones

Lunda Wick, Shetland

Segebad Detken: “HIR LIGHT DER EHRSAME / SEGEBAD DETKEN BVRGER / VND KAUFFHANDELER ZU / BREMEN [HE] HETT IN DISEN / LANDE SINE HANDELING / GEBRUCKET 52 IAHR / IST [ANNO 1573] DEN / 20 AUGUSTI SELIGHT / IN UNSEN HERN ENT / SCHLAPEN DER SEELE GODT GNEDIGH IST.”

Hinrick Segelcken: “ANNO 1585 DEN 25 IULII / UP S. JACOBI IS DE EHRBARE / UND VORNEHME HINRICK / SEGELCKEN DE OLDER UTH / DUDESCHLANT UND BORGER / DER STADT BREMEN ALHIR / IN GODT DEM HERN ENTSCHL / APN DEM GODT GNEDICH IS.”

Helgafell, Iceland

Clawes Lude: “Anno 1585 de.3. Junius starff clawes lüde van Bremen der olde. Dem godt gnedich seij.”

Þykkvabær, Iceland

Hans Berman: “HIR LICHT BEGRAVEN SALICH HANS BIRMA[N] D:I:V:H [i.e. “De Junger van Hamborg”] ANNO 1583.”

Further reading

Hofmeister, Adolf E. Sorgen eines Bremer Shetlandfahrers: Das Testament des Cordt Folkers von 1543. Bremisches Jahrbuch 94 (2015): 46–57.

Holterman, Bart. The Fish Lands. German Trade with Iceland, Shetland and the Faroes in the Late 15th and 16th Century. PhD thesis, Universität Hamburg, 2018.

Koch, Friederike Christiane. Das Grab des Hamburger Hansekaufmanns Hans Berman/Birman in Þykkvibær/Südisland. Island. Zeitschrift der Deutsch-Isländischen Gesellschaft e.V. Köln und der Gesellschaft der Freunde Islands e.V. Hamburg 5.2 (1999): 45.

MacDonald, George. More Shetland Tombstones. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 69 (1934): 27–48.

German merchants at the trading station of Básendar, Iceland

Bart Holterman, 9 March 2018

The German merchants who sailed to Iceland in the 15th and 16th century used more than twenty different harbours. In this post we will focus on one of them: Básendar. The site is located on the western tip of the Reykjanes peninsula and was used as a trading destination first by English ships, then German merchants from Hamburg and later by merchants of the Danish trade monopoly. Básendar is mentioned in German written sources with different spellings as Botsand, Betsand, Bådsand, Bussand, or Boesand.

Aerial image of Básendar (marked with the red star), located on the Western end of Reykjanes peninsula, and Keflavík airport on the right (image Google Earth).

Básendar was one of the most important harbours for the winter fishing around Reykjanes. In the list of ten harbours offered to Hamburg in 1565, it is the second largest harbour, which annually required 30 last flour, half the amount of Hafnarfjörður (the centre of German trade in Iceland). German merchants must have realised it´s potential at a very early stage, and it is therefore the first harbour which we know to have been used by the Germans, namely by merchants from Hamburg, in 1423.

The trading station was located on a cliff just south of Stafnes, surrounded by sand. Básendar was always a difficult harbour, exposed to strong winds and with skerries at its entrance. Ships had to be moored to the rocks with iron rings. The topography of the site also made the buildings vulnerable to spring floods, and during a storm in 1799 all buildings were destroyed by waves, leading to the abandonment of the place. Today, the ruins of many buildings can still be seen, as well as one of the mooring rings, reminding the visitor of the site’s former importance.

Básendar also became a place for clashes between English and German traders. Already the first mention of Germans in the harbour came from a complaint by English merchants that they had been hindered in their business there. In 1477 merchants from Hull complained as well about hindrance by the Germans and in 1491 the English complained that two ships from Hull had been attacked by 220 men from two Hamburg ships anchoring in Básendar and Hafnarfjörður.

The famous violent events of 1532 between Germans and English started in Básendar as well, when Hamburg skipper Lutke Schmidt denied the English ship Anna of Harwich access to the harbour. Another arrival of an English ship a few days later made tensions erupt, resulting in a battle in which two Englishmen were killed. The events in 1532 marked the end of the English presence in Básendar, and we hear little about the harbour in the years afterwards. The trading place seems to have been steadily frequented by Hamburg ships, sometimes even two per year. In 1548, during the time when Iceland was leased to Copenhagen, Hamburg merchants refused to allow a Danish ship to enter the harbour, claiming that they had an ancient right to use it for themselves.

Hamburg merchants were continuously active in Básendar until the introduction of the Danish trade monopoly, except for the period 1565-1583, when the harbour was licensed to merchants from Copenhagen. From 1586 onwards, the licenses were given to Hamburg merchants again. These are the merchants who held licences for Básendar:

1565: Anders Godske, Knud Pedersen (Copenhagen)

1566: Marcus Hess (Copenhagen)

1569: Marcus Hess (Copenhagen)

1584: Peter Hutt, Claus Rademan, Heinrich Tomsen (Wilster)

1586: Georg Grove (Hamburg)

1590: Georg Schinckel (Hamburg)

1593: Reimer Ratkens (Hamburg)

1595: Reimer Ratkens (Hamburg)

The last evidence we have for German presence in Básendar provides interesting details about how trade in Iceland operated. In 1602 Danish merchants from Copenhagen concentrated their activity on Keflavík and Grindavík. A ship from Helsingør, led by Hamburg merchant Johan Holtgreve, with a crew largely consisting of Dutchmen, and helmsman Marten Horneman from Hamburg, tried to reach Skagaströnd (Spakonefeldtshovede) in Northern Iceland, but was unable to get there because of the great amount of sea ice due to the cold winter. Instead, they went to Básendar which was not in use at the time. However, the Copenhagen merchants protested. King Christian IV ordered Hamburg to confiscate the goods from the returned ship. In a surviving document the involved merchants and crew members told their side of the story. They stated that they had been welcomed by the inhabitants of the district of Básendar, who had troubles selling their fish because the catch had been bad last year and the fish were so small that the Danish merchants did not want to buy them. Furthermore, most of their horses had died during the winter so they could not transport the fish to Keflavík or Grindavík and the Danes did not come to them. The Danish merchants were indeed at first not eager to trade in Básendar, and did not sail there until they moved their business from Grindavík in 1640.

Further reading

Ragnheiður Traustadóttir, Fornleifaskráning á Miðnesheiði. Archaeological Survey of Miðnesheiði. Rannsóknaskýrslur 2000, The National Museum of Iceland.

Newspaper article: Umsvif Hansakaupmanna á Íslandi til rannsóknar

Bart Holterman, 5 January 2016

Finally a summary of our project written in Icelandic! Published in Morgunblaðið, 15 December 2015. With kind permission of the author Guðni Einarsson.

Posted in: Press

When sailing North, beware of swimming cows and Hamburgers. The Carta Marina and the North Atlantic

Bart Holterman, 5 October 2015

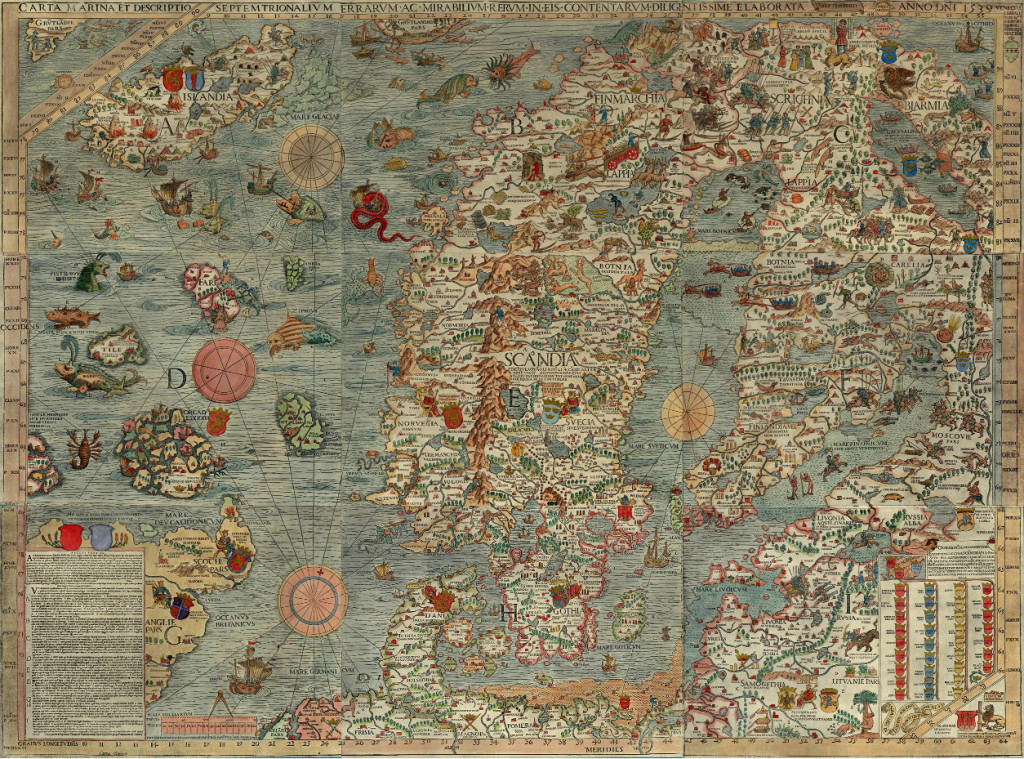

For the banner of this blog and our facebook page, we have displayed a section of the famous Carta Marina from 1539. On a first glance of the map, the many marvellous creatures that inhabit the land and the sea immediately catch the eye of the beholder, yet it also provides us with a good overview of the contemporary North Atlantic trade. Time to explore this remarkable document a bit further.

The map was made by Olaus Magnus (1490-1557), the brother of the last catholic bishop of Sweden. He had travelled Scandinavia and the lands around the Baltic Sea extensively before he was sent on a diplomatic mission to Rome by the Swedish king Gustav Vasa. He was never to return home. Dissatisfied by the Reformation in his homeland, Magnus stayed abroad, first in Lübeck and Danzig, later for a long time in Italy, soon joined by his expelled brother Johannes Magnus. In Italy he kept close contacts to learned men of his age, among others cartographers and travellers.

Under influence from these social circles, Magnus decided to transform his own knowledge about Northern Europe onto a map, which would appear in print in Venice in 1539. It was the first large-scale map of Scandinavia to be ever made, and had much influence on European cartography for the next decades. However, because of its high costs, the number of copies remained low. The map itself disappeared off the map of European learning, and was deemed to be lost since the late sixteenth century. Luckily in 1886 an intact copy of the map was discovered in the Bavarian State Library in Munich, and in 1961 another one, which now resides in Uppsala.

An explanation of the map appeared only in 1555 as Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus. In this book, Olaus Magnus described the geography, wildlife, and customs of the people of the North, illustrated with woodcuts. These woodcuts are clearly based on parts of the map, which includes many details about the people of the North, the political situation of the time, and the nature and wildlife. We can see kings sitting on their thrones, armies crossing the frozen Baltic Sea, people hunting seals, the most important towns and cities, lighthouses, whales attacking ships, enormous snakes, swimming cows and other sea monsters.

The map is divided into nine parts, marked A-I. It covers the entire Scandinavian peninsula, the Baltic, Northern Germany and the Netherlands, the entire North Sea and North Atlantic, including the coastline of Britain, the southern tip of Greenland and the mythical island Thule, known from classical geographical works. Of our interest are mainly the sections A and D, covering a large part of the North Atlantic.

Olaus Magnus probably never visited the North Atlantic himself. Instead, he had to rely on the stories and descriptions of others, for example the Northern German traders that told him about Iceland, the Shetlands and the Faroe Islands. Of the Shetlands and Faroes, Magnus must have had few information, as these archipelagos are only schematically drawn. One remarkable detail can be found on the Faroes, though, where we can see a whale being slaughtered on the shore, reminiscing a practice of hunting whales by driving them up the shore which is still practiced today.

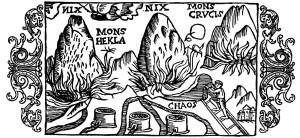

For Iceland, Magnus was clearly better informed. The Carta Marina was the first map that drew the island in its more or less actual shape. Moreover, three vulcanoes attest to Magnus’s knowledge of the high vulcanic activity on the island. The two episcopal sees, Hólar (Holensis) and Skálholt (Scalholdin), are displayed, as well as the monastery Helgafell (Abbatia Helgfiall), which was famed for its butter production (butirum). The three knights on the eastern part of Iceland should probably be seen as an indication of Danish military presence on the island.

Three volcanoes on Iceland, from Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (1555), photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Better than the natural, religious, and political situation, the map attests of the economic situation. Firstly, the main export goods of Iceland are indicated. These are, besides the already mentioned butter: stockfish, sulphur, and falcons. Stockfish was dried cod, highly valued in Europe as a preservable source of protein, and the main trade good of the arctic region. It is shown on a pile on the south coast. Just north of it, three containers of sulphur are depicted. Iceland was one of the few places where pure sulphur could be found. Sulphur, being among others a key ingredient for making gunpowder, was a highly valued substance. Finally, a gyr falcon (falco albus) can be seen on one of the northern peninsulas of Iceland. Gyr falcons are only found in arctic regions, and due to its being the largest and strongest species of falcon, it was highly valued by the nobility for use in falconry.

Apart from the export goods, the realities of the north atlantic trade are displayed in considerable detail on the map. Various trading harbours are indicated, most notably Hafnarfjörður (Hanafiord), where merchants from Hamburg had built a church. We can see ships lying at anchor at these harbours, and three tents at Ostrabord, which probably indicate the temporary booths the merchants set up on the shore and where they displayed their goods on sale during the summer.

The most important countries and cities trading with the island are also indicated. We can see a ship from Bremen at anchor near Ostrabord, an English ship which confused a whale for an island, a ship from Lübeck being attacked by whales, and a Scottish ship under attack by one from Hamburg, indicating the dominance of Hamburg in the North Atlantic trade. It was no exception that competition between merchants from different places led to violent clashes, as in 1523, when the crews of ships from Bremen and Hamburg attacked an English ship in a conflict over the rightful ownership of an amount of stockfish, resulting in casualties among the English.

These elements make the Carta Marina a wonderful visual testimony of the North Atlantic trade in the sixteenth century.

Posted in: Sources