Worth a fortune: Icelandic gyrfalcons

Natascha Mehler, 11 August 2016

Throughout the medieval and early modern period, Icelandic gyrfalcons were highly valued at the courts of European rulers and they were worth a fortune. Indeed, Frederick II (1194-1250), Holy Roman Emperor, already noted in his treatise De arte venandi cum avibus that the best falcons for use in falconry were gyrfalcons (…et isti sunt meliores omnibus aliis, Girofalco enim dicitur). The reason for this was that of all falcon species, gyrfalcons (Falco rusticolus) are the largest and most powerful. Their plumage varies greatly from completely white to very dark, of which the white variety was the most valued hawking bird in the Middle Ages, and still is today. They only inhabit sub-arctic and arctic areas, with their highest population density in Iceland (one pair per 150-300 km²). During the breeding season (roughly February to June) there are today 200-400 nesting pairs in Iceland, and in the winter the population increases to 1.000-2.5000 individuals, due to migrating birds from Greenland.

Written sources from the 16th century, when German merchants from Hamburg and Bremen dominated the trade with the North Atlantic islands, give us a better insight into the falcon business with Iceland. Matthias Hoep, a Hamburg merchant, has left behind a collection of account books (1582-1594) which show us that he traded in many commodities such as fish, timber, and tools, and specialized in the trade of falcons. Hoep employed falcon catchers to catch birds in Iceland for him and he made specific contracts with them. The books record a great number of falcons and other birds of prey that he bought from falcon catchers and which he then sold on. On 5 April 1584, Hoep made a contract with the falcon catchers and brothers Augustin and Marcus Mumme which he commissioned to travel to Iceland to catch falcons. The contract specified the bird species, the conditions of the birds upon delivery, and the prices Hoep was going to pay after the successful return of the Mummes from Iceland:

“On 5 April [1584] I have dealt in my house with Augustin and Marcus Mumme, in the name of god, that they shall sail to Iceland in the name of god, and we agreed that I will give for each pair of falcons 11 ½ daler, and 2 tercel [male falcons] for 1 falcon, and what is blank shall be counted as a red [unmoulted] falcon. But what is white and moulted once, or moulted twice and beautiful, for those I shall give them 20 daler for each falcon and 10 daler for a tercel. But what has moulted three times we shall agree upon with good will, and if god and luck provides them with white falcons, I will give the one who catches them black cloth for a jacket of 2 ½ ells, all of this is validated with a denarius dei of 1 sosling each, and both brothers have promised with an oath to bring the best birds they can get and to take no birds away, neither in Iceland nor during the journey back, until they have all been delivered to me.“

Roughly five months later, in September 1584, the brothers returned from Iceland and handed over 49 birds to Matthias Hoep.

Detail of the Carta Marina (1539) showing the coat of arms of Iceland (stockfish), with a gyrfalcon (FALCO ALBI) above.

Later documents tell us how the shipping of the falcons was done. During the 17th century, a Danish falcon ship went to Iceland annually to transport falcons from Iceland to Copenhagen. The falcons were kept below the deck and sat on poles which were lined with vaðmál. During the journey, the birds were fed with meat of cattle, sheep or birds, dipped in milk, and when they were sick, they were fed with a mix of eggs and (fish) oil. Upon arrival of the birds in Hamburg, Mathias Hoep checked their health and quality and he considered them in good state after they had eaten three times and their feathers were not broken.

Most of the birds that Hoep received were sold to English merchants such as John Mysken who bought 55 birds of prey in 1584 and had them shipped to England, most likely to be sold to the English court. It is likely that Hoep also had good contacts with Icelanders, both in Iceland and in Hamburg. His professional network may have included Magnús Jónsson (c. 1530-1591), who had studied law in Hamburg, probably until 1556. In Iceland he became chieftain and sýslumaður (sheriff) at Þingeyjaþingssýsla and Ísafjarðarsýsla, districts in the North of Iceland with a very high density of falcons. No wonder his seal from the year 1557 shows a gyrfalcon in the centre.

Seal of Magnús Jónsson, dated 1557. The priest Ólafur Halldórsson, a contemporary of Magnús Jónsson, described the seal in a poem: „Færði hann í feldi blá, fálkann hvíta skildi á, hver mann af því hugsa má, hans muni ekki ættin smá.” (transl. „he carried in a blue field, a white falcon on his shield, so that everybody shall think his family is not insignificant“).

In the second half of the 16th century, king Frederick II of Denmark-Norway (1559-1588) started to regulate the export of falcons to foreign countries. From the 1560s onwards, foreign falcon catchers needed to buy a permission (Icel. fálkabréf, falcon letter) to catch falcons.

Were falcons also caught in Shetland or the Faroes?

We have not found any written evidence for that. The obvious reason for this is that there are not many falcons around in Shetland and the Faroes. Gyrfalcons only appear as vagrant birds, and peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) exist in Shetland only in small numbers. However, it is worth pointing out that in the years 1601 to 1606 one Tonnies Mumme is recorded to have sailed each summer from Hamburg to Shetland. We do not know whether this is the same Tonnies Mumme that is reported as falcon catcher in Iceland in previous years, or whether Tonnies is related to the Augustin and Marcus Mumme mentioned above, but it seems very likely. He may have tried his luck in Shetland, or might have changed his profession and have traded in other items.

Further reading

Natascha Mehler, Hans Christian Küchelmann & Bart Holterman, The export of gyrfalcons from Iceland during the 16th century: a boundless business in a proto-globalized world. In: Gersmann, Karl-Heinz & Grimm, Oliver (eds.): Raptor and human – falconry and bird symbolism throughout the millennia on a global scale, vol. 3, Advanced studies on the archaeology and history of hunting 1 (Neumünster 2018), 995-1019.

Kurt Piper, Der Greifvogelhandel des Hamburger Kaufmanns Matthias Hoep (1582-1594). Jahrbuch des Deutschen Falkenordens (2001/2002), 205-212.

Björn Þórðarson, Íslenzkir fálkar. Safn til sögu Íslands og íslenskra bókmennta (Reykjavík 1957).

Posted in: Stories

Sailors, merchants and priests: people on board the ships heading North

Bart Holterman, 13 May 2016

The general history of the northern German trade with the North Atlantic is relatively well known but we know very little about the persons involved in this trade. This is especially true for the men that manned and sailed the ships that headed North.

Luckily, there are a couple of sources pertaining to the North Atlantic trade that give us a good insight into the people on board the ships. First, two boarding lists from Oldenburg for ships trading with Iceland in the 1580s have survived. Second, there is the magnificent book of donations of the Hamburg confraternity of St Anne, the socio-religious organisation behind the trade with Iceland, Shetland, and the Faroe Islands. From the 1530s onwards, the register lists the alms spent to the confraternity by the people on board of nearly every ship that returned to Hamburg, resulting in a more or less complete register of boarding lists.

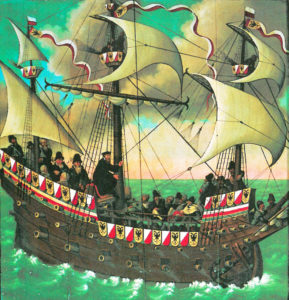

On board a sixteenth-century ship: detail of the epitaph for the ship´s priest Sweder Hoyer (deceased 1565) from the St Jacob church in Lübeck. Note: this image does not necessarily reflect the situation on board the merchant ships in the North Atlantic.

From these sources we can learn that the number of people on board varied greatly, ranging from 77 on larger ships up to around 10 on board the smallest vessels. For Iceland, it was not uncommon to have more than 25 people on board. Ships sailing to Shetland and the Faroe Islands had less people on board, usually 15-20.

This difference in number of people on board was mainly caused by the number of merchants on board. The sizes of the crews were relatively similar on each ship, because 10 to 15 people were needed to sail the ship, regardless of its size. A typical crew consisted of:

– Skipper (schipper). He was the captain, the leader of the ship, often also one of the merchants, and (partly) shipowner.

– Helmsman (sturman), the one who steered the ship and had navigational knowledge.

– Chief boatswain (hovetbosman), the leader of the sailors.

– Schimman, the officer responsible for rigging and other technical things.

– Cook (koch).

– Carpenter (tymmerman), responsible for repairs to the ship.

– Gunner (buchsenschut), responsible for the defense of the ship.

– Barber (bartscher), who had medical knowledge, but lacked on most ships.

– 2-4 sailors (bosman).

– 1-2 ship boys (putker), young sailors in training.

Besides these, ships transported merchants and their servants, falcon catchers, priests, and passengers from the islands which used the regular traffic to travel to and from the European mainland.

Further reading:

B. Holterman, Size and composition of ship crews in the German trade with the North Atlantic islands. In: N. Mehler (ed.), Traveling to Shetland, Faroe and Iceland in the early modern period (Leiden, in press).

F. C. Koch, Untersuchungen über den Aufenthalt von Isländern in Hamburg für den Zeitraum 1520-1662. Beiträge zur Geschichte Hamburgs 49 (Hamburg 1995).

Uncovering the North Atlantic trade sherd by sherd

Natascha Mehler, 12 April 2016

When it comes to the goods transported by merchants from Bremen and Hamburg to the North Atlantic islands we have only limited sources at hand. The few extant account books list the commodities they sold to the inhabitants of the islands in return for stockfish, fish oil, sulphur or woolen cloth. But the written sources are not precise but rather general and never tell where the exported goods were manufactured. To complicate matters, (archaeological) material culture of the German period is scarce. Most of the goods traded by the Germans were bulk material such as grain or flour, cloth, timber, and beer, and to a lesser extent every day items that were hard to get on the islands: horse shoes, tools, knifes, wax etc. Many of these goods, especially those of organic material, have long been gone. Ceramics, however, are a different matter. Icelanders did not produce ceramic vessels (and the Faroese and Shetlanders only to a limited extent) which means that all pots, pans, jugs and beakers needed to be imported. A considerable amount of pottery from the 15th to 17th centuries has been found in Iceland, Shetland and Faroe but what can pottery sherds tell us about that trade?

Fragments of a so called “Schnelle”, a tankard produced in Siegburg in the 16th century, found at Tórshavn, the German trading station in the Faroe islands (photograph by Helgi Michelsen).

The sherds that have survived from excavations and in museum collections in Iceland show characteristic traits of wares common in Northern Europe. The ceramic assemblages of sites such as Gautavík (a German trading site in the East), Viðey (a monastery near Reykjavík), or Stóraborg (a farm at the South coast) consist of two distinctive ware groups: stonewares and redwares. Stoneware was used to produce drinking vessels such as jugs and beakers. They were widely traded over Northern Europe, via the river Rhine and ports of Northern Germany and the Netherlands. For the trained eye, these stonewares are relatively easy to determine. The majority stems from the famous medieval and early modern production centres along the Rhine such as Siegburg, Frechen, or Cologne; a second group can be traced back to Lower Saxony.

The origin of redwares, a general term for cooking vessels (pots, pans) and plates consisting of earthenware, is far more problematic to identify. Vessel shapes and fabrics of pottery workshops are generally very similar over a large area and it is therefore hard to determine where exactly a certain redware pot was produced. Distinguishing the redwares is mostly based on typological characteristics such as a distinctive form of the rim of a pot, but the Icelandic archaeological material is often too fragmented to allow an identification beyond doubts. However, provenancing these redwares would considerably change our understanding of the trade mechanisms and pottery consumption patterns in the North Atlantic.

Fragmented redware tripod with internal lead glaze found at the trading site of Gautavík, Iceland. It dates to the late 16th century but the place of origin remains enigmatic (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

Luckily, there are other methods than typology to identify the provenance of pottery. In recent years, ICP analysis (inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry), widely used in archaeological science, has proven to be a reliable method to determine the chemical fingerprint of the clays used for the production of ceramic vessels. ICP analysis has been applied successfully at a large number of redwares produced in Southern Scandinavia and Germany, with ground breaking work done by Torbjörn Brorsson (Kontoret för Keramiska Studier, Sweden) and Jette Linaa (Moesgaard Museum, Denmark). This means that we now have a solid base of reference material at hand which is necessary to securely identify the origin of the redwares in question. The application of the method in ceramic studies and an overview on the data reference material was presented in April 2016 at the inaugural meeting of the Baltic and North Atlantic Pottery Research Group (BNPG) which took place at the Historiska Museet Stockholm.

In summer 2016, redware fragments from selected sites in Iceland, Shetland and Faroe will be sampled in order to conduct ICP analysis. We will report on the results of the analysis, and what this means for the interpretation of the trading connections between Northern Germany and the North Atlantic islands.

Further reading:

Torbjörn Brorsson, A new method to determine the provenance of pottery – ICP analysis of pottery from Viking age settlements in Northern Europe. In: S. Kleingärtner, U. Müller, J. Scheschkewitz (eds.), Kulturwandel im Spannungsfeld von Tradition und Innovation. Festschrift for Michael Müller-Wille. Neumünster, 2013, 59-66.

Adolf Hofmeister, Das Schuldbuch eines Bremer Islandfahrers aus dem Jahre 1558. Bremisches Jahrbuch 80, 2001, 20-50.

Natascha Mehler, Die mittelalterliche Importkeramik Islands. Current Issues in Nordic Archaeology. Proceedings of the 21st Conference of Nordic Archaeologists, 6-9 September 2001, Akureyri, Iceland. Reykjavik 2004, 167-170.

Newspaper article: Umsvif Hansakaupmanna á Íslandi til rannsóknar

Bart Holterman, 5 January 2016

Finally a summary of our project written in Icelandic! Published in Morgunblaðið, 15 December 2015. With kind permission of the author Guðni Einarsson.

Posted in: Press

Lecture about current research in past cod fisheries in the North Atlantic

Natascha Mehler, 14 October 2015

On Wednesday, 4 November 2015, Dr. Guðbjörg Ásta Ólafsdóttir and Dr. Ragnar Edvardsson, University of Iceland, will speak about their new research project on the history of cod fishing in the North Atlantic. The lecture takes place at the German Maritime Museum in Bremerhaven, starting 14:00, and is open to anyone interested. Here is a short summary about the content of the lecture.

Posted in: Announcements