The enigmatic Icelandic hare, which turned into a sock

Hans Christian Küchelmann, 4 January 2021

Writing about Hamburg trading connections with Iceland in 1899, Richard Ehrenberg mentions cursorily in a footnote that Hamburg merchants received hares from Icelanders (Ehrenberg 1899, 25). He refers to an entry in the donation register of the Annenbruderschaft (confraternity of St. Anne). The Annenbruderschaft was a caritative organisation, for which Hamburg merchants trading with Iceland, Shetland and the Faeroes regularly gave money after returning from their journeys. The account book lists goods bought in Iceland and the donations given as a share to the fraternity for the period 1533-1628. The specific entry concerns the donations of the ship’s crew of skipper Marten Horneman after their journey to Iceland in 1587 and reads:

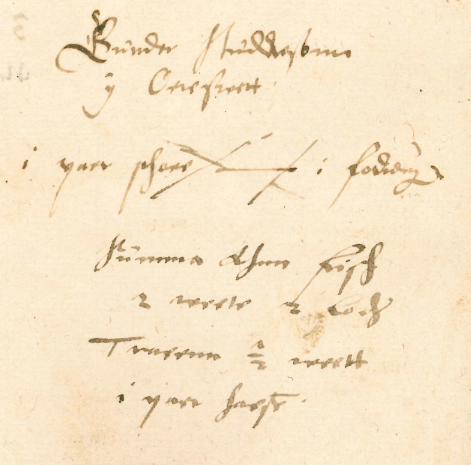

„item up der Öhe geschattet 15 hovet f und 1 par hasen darvor 5 s“.

(Staatsarchiv Hamburg 612-2/5, Kaufmannsgesellschaft der Islandfahrer, Annenbruderschaft, 1520-1842, 2, Band 1, folio 327r; see HansDoc, document ID 15330000HAM00).

Bart Holterman transcribed and analysed several hundred historic documents relating to Hanseatic North Atlantic trade for his PhD-thesis (Holterman 2020; Holterman & Nicholls 2018), which allows us to decipher the data given in the documents in more detail:

• „Öhe“ is a lower German term for island and since we know from the account book that Marten Hornemann traded in Keflavík (Kibbelwick), Reykjanes peninsula, from 1586-1595 it will have been an island near this trading station.

• „schatten“ is a legal term comparable to a monetary fine, indicating that somebody had to pay a fine for something not further specified.

• „f“ is the shortcut for fish used throughout the whole document. From the overall context we can be almost certain that „fish“ always indicates cod (Gadus morhua) prepared as stockfish. Stockfish made from cod is the bulk item bought by German merchants in Iceland and all other fish species or product types are usually indicated as such separately. We are not yet certain what „hovet fisch“ indicates in particular. „Hovet“ is lower German for „Haupt“ (= main, head, capital), so we assume so far that it is a large kind of stockfish.

• „Hase“ is the German name of the hare (Lepus europaeus).

• „5 s“ specifies that 5 shilling have been given to the confraternity as share of the items received.

• A term that will become crucial in the interpretation is „1 par“. The German speciality with the modern word „paar“ or „Paar“ is that it can have two different meanings. If written with a capital P as „Paar“ it means „pair“ specifying (exactly) two items which are connected to each other, like e. g. a pair of gloves or two people married to each other (Ehepaar). If written with a small p it denotes a small but uncertain number of items: „ein paar Kekse“ being „some cookies“.

Summarised, the information given is that skipper Marten Horneman received 15 (large?) stockfish and some hares as a fine from somebody on an island near Keflavík and gave five shilling to the St. Anne confraternity for this. Further research for hasen in the Iceland trade documents revealed that hasen appear in fact three times in the account book of the Annenbruderschaft in similar contexts:

folio 369 r (1592): “Noch van Jon lochman vor norden den armen gegeven 9 ele min 1 q(uart?) wadtman und 1 par hasen darvan gekamen in gelde.“

folio 398r (1596): “Otte Eddelman 1 par hasen darvor entfangen,“

Jon Lochman is better known as Jón Jónsson, lawmen (ĺögmaður) in northern and western Iceland at the end of the 16th century, who is known to have cooperated closely with German merchants.

Additionally, there is another document, which lists hasen being bought from Icelanders: An account book of merchants from Oldenburg trading 1585 in Neßwage (Nes), Snæfellsnes peninsula, mentions hasen four times:

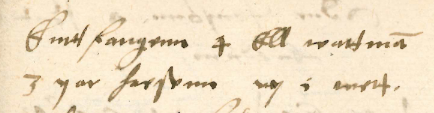

page 38: “1 paer haesen“

page 38: “1 par haesen 1 fordung […] 1 paer haesen“

page 45: “3 par haesenn up 1 wett“

(Stadtarchiv Oldenburg, Rechnungsbuch über die 1585 in Island verkauften Waren, Best. 262-1, no. 3; Holterman 2020, 45; HansDoc ID 15850000OLD00).

This is a good example for the advantage of interdisciplinary research. From the historic point of view the interpretation here is clear and unequivocally: hares were among the goods bought in Iceland (see Holterman 2020, 45). They were not an item of major importance, but at least appear several times in the 16th century Hanseatic trade in different locations in western Iceland on the Snæfellsnes and Reykjanes peninsulae. From the zoological point of view, however, a major interpretation problem evolves here. According to zoogeographical sources, hares do not inhabit Iceland, neither the European hare (Lepus europaeus) nor the snow hare (Lepus timidus) (see e. g. Grimberger et al. 2009, 211-212, 214-216; see also the list of mammals of Iceland). There are neither archeozoological nor palaeontological records of hares from Iceland, indicating that the genus ever inhabited the island.

Important here, and even more convincing from the historic point of view, is an account of Arngrimur Jónsson from 1593, who states in his “Brevis commentarius …“ that:

“Eodem crimine tenentur, quicunque; Islandiæ, coruos albos, picas, lepores, et vultures adscripserunt: Perrarò enim vultures, cum glacie marina, sicut etiam vrsos (sed hos sæpius quam vultures) et cornicum quoddam genus, Islandis Isakrakur, aduenire obseruatum est. Picas verò et lepores, vt et coruos albos, nunquam Islandia habuit.“

(Jónsson 1593, sectio 14, quoted after Hakluyt 1598).

Jónsson refers to the description of a not specified author, who claims the mentioned species (white ravens, magpies, hares and vultures) as resident species of Iceland. He is very precise in his comment and disclaims this notion clearly as being wrong, except for vultures, which sometimes reach Iceland with the sea ice. Thus, zoological, archaeozoological and additional historic evidence points to a wrong interpretation of the Low German term hasen as hares here. However, there is one slight possibility that needed to be cross-checked before refuting hares and searching for alternative interpretations. One species frequently mistaken for hares, at least by non-specialists, is the rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Rabbits spread in Europe from the 12th century onwards, first as gifts changed between monasteries. They were high status animals first, jealously guarded by monastic circles and the gentry, becoming more widespread since the 16th century (Benecke 1994, 356-361; Küchelmann 2010, 183-184). Therefore, an introduction of rabbits to Iceland in medieval or early modern time is theoretically not impossible. I am grateful to Lísabet Guðmundsdóttir (Institut of Archaeology Reykjavik), who kindly checked this question:

„Rabbits are a modern intrusion to Iceland, being imported as pets, which were let loose, mostly around Reykjavík but they have also become an ecological problem in Vestmannaeyjar since they are using puffin holes as habitation and the puffins usually use the same ones again and again. They are also living in areas around Akureyri at present. The oldest example of “wild” rabbits in Iceland (that I know of) is from 1942, a farmer in Saurbjæjarhlíð in Hvalfjarðarströnd started to breed rabbits around 1932 but some had gotten away and had started to breed in the wild at least in 1942 (see Morgunblaðið 7.3.1942). Rabbits had been imported earlier to Iceland but had never been able to survive the winters but now they can. At present the numbers of them are rising instead of declining which is not good since they are causing havoc to the quite sensitive Arctic environment.“ (Guðmundsdóttir, personal comm. 16. 11. 2020).

Summarising the historical and zoological information, it seems unlikely that hares could have been bought by the Hanseatic merchants in Iceland. Even the slight possibility of introduced rabbits is extremely unlikely. Reanalyzing the historic accounts and searching for alternative interpretations the above mentioned word „par“ becomes important. In all seven evident cases of the term „hasen“ bought in Iceland, they appear in combination with the word „par“. They never occur as single items (1 hase) nor in an uneven number (e.g. 3 or 5 hasen). This makes it likely that in this case „par“ does not mean an uncertain small number of hasen, but that instead hasen are a good regularly traded in pairs. The most probable solution here is that of a sound shift from o to a. „Hosen“ is the German term for trousers, which then would make perfect sense as a „pair of trousers“. Indeed, there is historical evidence for a sound shift from o to a in several Middle Low German words related to hosen, which are listed e. g. in the Middle Low German word books of Köbler (2014) and Schiller & Lübben (1876/1995, 212, 305-306). Vaðmal and trousers – two textile goods – donated by Jón Jónsson in 1592 would also fit well together. The term „1 par hasen“ also appears in another document related to Icelandic trade: The account book of the Bremen merchant Clawes Monnickhusen, who traded 1557-1558 in Kummerwage (= Kumbaravogur, Snæfellsnes), lists hasen two times. But here the hasen appear in that part of the document listing debts of his customers in Bremen 1560-1577. The hasen again are listed as pairs, adding weight to the argument of a sound shift:

folio 24r (1571): „Item den man dar ick den ossen van krech XV grote vor I par hasen.“

folio 30r (1575): „Item Devert Jebelman I par hasen XX grote.“

(Staatsarchiv der Freien und Hansestadt Bremen 7,2051 (formerly Ss.2.a.2.f.3.a.), HansDoc ID 15570000BRE00).

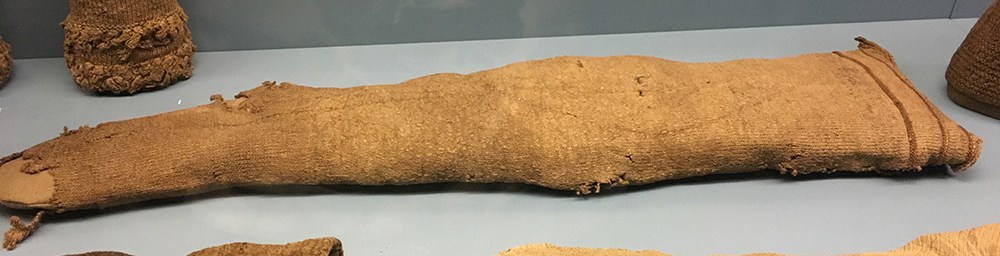

To conclude, the former interpretation of the term hasen as the zoological species Lepus can be refuted, but the entries then become an interesting evidence for Icelandic textile production and trade. According to Michèle Hayeur Smith, researcher on historic textiles at the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, Brown University, Bristol, Rhode Island, USA, the trousers bought by the Hanseatic merchats in Iceland most probably were knitted stockings:

„In the 16th century they were in the habit (in Europe) of wearing long knitted stockings, in fact it was all the rage. Knitting was introduced into Iceland in 1500 and I know that the Icelanders and Faroese were busy knitting for these foreign markets and one of the main things they were knitting were stockings. I think that we are probably not talking about hosen as trousers, but rather as stockings and sold in pairs would make a lot of sense.“ (Hayeur Smith, personal comm. 17. 11. 2020).

For further research on Icelandic knitted stockings see e. g. Thirsk (2003), Róbertsdóttir (2008) or Hayeur Smith et al. (2018, 5).

References:

• Benecke, Norbert (1994): Der Mensch und seine Haustiere, Stuttgart

• Ehrenberg, Richard (1899): Aus der Hamburgischen Handelsgeschichte, Zeitschrift des Vereins für Hamburgische Geschichte 10, 1–40

• Grimmberger, Eckhard / Rudloff, Klaus / Kern, Christian (2009): Atlas der Säugetiere Europas, Nordafrikas und Vorderasiens, Münster

• Hakluyt, Richard (1598): The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation, v. 1, Northern Europe

• Holterman, Bart (2020): The Fish Lands. German trade with Iceland, Shetland and the Faroe Islands in the late 15th and 16th century, Berlin

• Hayeur Smith, Michèle / Lucas, Gavin / Mould, Quita (2018): Men in Black: Performing masculinity in 17th- and 18th-century Iceland. – Journal of Social Archaeology 0(0), 1-26

• Holterman, Bart & Nicholls, John H. (2018): HANSdoc Database, Bremerhaven

• Jónsson, Arngrímur (1593): Brevis commentarius de Islandia

• Köbler, Gerhard (2014): Mittelniederdeutsches Wörterbuch, 3. Ausgabe, Erlangen

• Küchelmann, Hans Christian (2010): Vornehme Mahlzeiten: Tierknochen aus dem Dominikanerkloster Norden. – Nachrichten aus Niedersachsens Urgeschichte 79, 155-200

• Róbertsdóttir, Hrefna (2008): Wool and society, Reykjavík

• Schiller, Karl & Lübben, August (1876/1995): Mittelniederdeutsches Wörterbuch, Zweiter Band: G–L, Vaduz

• Thirsk, Joan (2003): Knitting and Knitwear, c 1500-1780. in: Jenkins, David (ed.): The Cambridge History of Western Textiles I, 562-584, Cambridge

Posted in: General, Sources, Stories

Fish and Ships continues: new project about the international trade of Orkney and Shetland in the early modern period

Natascha Mehler, 27 March 2020

Over the past years, our research on the German trade with the North Atlantic islands has mainly focused on the exchange with Iceland. In the case of Shetland, however, much written and archaeological material exists which is of great potential to help uns understand the operation of international trade on the North Atlantic island. We therefore, we applied for a new grant in order to continue our work with Shetland. The project also addresses the question whether Orkney, which shares many characteristics with the other islands but hardly ever appears in the written sources, was also visited by German merchants in search of dried fish and if they did, to what extent and how this trade was organised. Finally, we will broaden our view to include other international (English, Dutch, Norwegian) traders in the area.

We are happy to announce that our team, together with other archaeologists and historians from the University of the Highlands and Islands Archaeology Institute and the University of Lincoln have been awarded a grant of c. 900.000 Euros from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the German Research Foundation (DFG) to do this. Over the next three years, the members of the project “Looking in from the edge (LIFTE)” will look at a number of early modern documents, objects from archaeological excavations and also conduct fieldwork in Orkney and Shetland. This also means that we will continue blogging on Fish and Ships for more stories and short research reports about pre-modern trade in the North Atlantic. Stay tuned!

Here are the links to our announcements in English and in German, with further information.

https://www.dsm.museum/pressebereich/der-lange-arm-der-hanse/

Posted in: Announcements, General

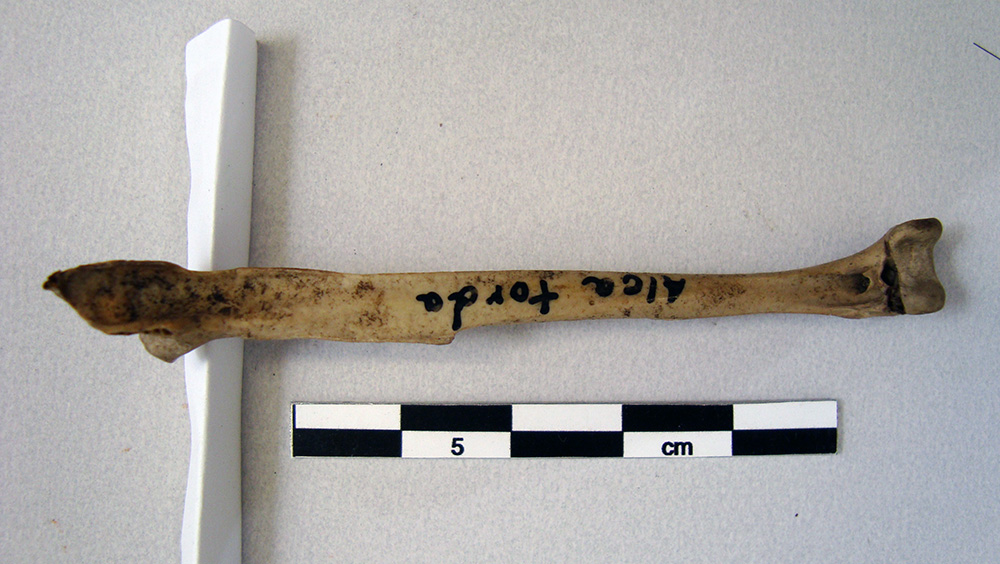

Razorbill in Bremen

Hans Christian Küchelmann, 20 March 2019

During excavations in 2011 in the former defense ditch of the city of Bremen huge amounts of animal bones have been found. The material has been analysed in the course of the Hanse Project since it contained a large amount of cod (Gadus morhua) bones. But there were also other interesting finds pointing to a trade connection with the North Atlantic. Of particular interest is a bone of a razor bill or lesser auk (Alca torda) with cut marks. This bird does not live on the North Sea coast and must have been brought to Bremen from North Atlantic regions e.g. from Shetland, Iceland, the Faroes or Northern Norway, probably as a by-product of the Bremen North Atlantic trade for stockfish.

Julia Schmidt, public relations officer of the Landesarchäologie Bremen, has written a blog about this find (in German) that can be accessed on the Facebook page of the Landesarchäologie.

Posted in: Announcements, General, Press, Stories

Till death do us part: Graves of sixteenth-century German merchants in the North Atlantic

Bart Holterman, 11 October 2018

When one has the chance to visit the northernmost island of Shetland, Unst, it is worth visiting the ruined church at Lunda Wick, in a bay to the Southwest of the isle. To get there, one has to take a small gravel road across a barren moory landscape where nothing seems to live but sheep and the occasional marsh bird. At the end of the path, one reaches a secluded bay where the grey waves and the rain torture the sands of the beach, and out of the fog a ruined medieval chapel appears with a graveyard around it. Inside the roofless chapel are a number of old tomb stones, the text made almost illegible by the lichen that overgrows them and centuries of rain and salty sea wind. In a corner lies a grave slab, on which it is possible to discern a text written in Low German, with great difficulty: “Here lies the honourable Segebad Detken, citizen and merchant from Bremen, who has traded in this country for 52 years, and died [in the year 1573], the 20th of August. God have mercy on his soul” (see below for the Low German text).

Segebad Detken is known from written sources about the Bremen trade with Shetland. He can be tracked from 1557 onwards as a skipper in the northern harbours Burravoe in Yell, and Baltasound and Uyeasound in Unst. In 1566, he was robbed by Scottish pirates in the harbour of Uyeasound. As his tomb slab mentions that he had been trading for 52 years in Shetland, he must have died in the late 16th century (see below). After his death, his relatives took over the business: among others his son Herman and grandson Magnus are recorded as merchants in northern Shetland in the early 17th century.

The grave slab of Segebad Detken in the ruined church in Lunda Wick. Photograph: Bart Holterman, 2018.

Given the long careers of German traders in the North Atlantic, and the fact that Bremen and Hamburg merchants dominated this trade for over 100 years (for Shetland even longer), it is not surprising that some of these merchants were buried on the islands when they died there. We can find another example just a bit outside the same church. There is another grave of a contemporary of Segebad Detken, that of his fellow citizen Hinrick Segelken. The Low German text on his slab translates as: “In the year 1585, the 25th of July, on St James’ day, the honourable and noble Hinrick Segelcken the Elder from Germany and citizen of the city of Bremen, died here in God our Lord, who has mercy on him.”

The tombstones were most probably imported by the German merchants, as the sandstone from which they were made is not available on the islands. By erecting a distinct grave marker for their deceased colleagues, they did not only honour their remembrance, but it also served to strengthen their ties with the local communities. The material and textual aspects of the monuments reminded the observer of the importance of the German merchants for the local economy, even across the boundaries of life and death.

A similar situation we find on Iceland, where we can also find tombstones of German merchants. The National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavik, for example, houses the tomb slab of Bremen merchant Claus Lude (follow link for an image), who was originally buried in the monastery Helgafell on the Snæfellsnes peninsula. The stone shows his house mark, a seal with two crossed stockfishes, and a text which mentions that he died on 3 June 1585. Lude is known to have been active in harbours in Snæfellsnes in the 1550s, and held a license for the harbour Grindavík in 1571.

In southern Iceland, at the graveyard of the former monastery Þykkvabær, one can still find the tombstone of Hans Berman the Younger from Hamburg, who died in 1583. The monastery records reveal that he was administrator of the monastic property (klausturhaldari) and was killed by the parish priest of Mýrar. His name also appears in the register of the Confraternity of St Anne of the Iceland merchants in Hamburg, where another Hans Berman (probably his father) was elderman around the same time.

In Hafnarfjörður near Reykjavík, the Hamburg merchants had their headquarters and also erected their own church. It is likely that they also had a graveyard where they buried their dead. During construction of the modern harbour of Hafnarfjörður in the 1940s, human bones were found which many believed to be from the old German graveyard in the town. It might even be possible that these bones once belonged to Hamburg merchant Hans Hambrock, the only death of a Hamburg merchant in Hafnarfjörður known from the written record. Hambrock had died from the injuries inflicted upon him by his colleague Hinrick Ratken, who drew his knife against him after Hambrock had hit Ratken on the head during a conflict about the unloading of a ship in 1599. Regrettably, the remains of the German church in Hafnarfjörður are now buried below the modern town.

Inscriptions on the discussed tombstones

Lunda Wick, Shetland

Segebad Detken: “HIR LIGHT DER EHRSAME / SEGEBAD DETKEN BVRGER / VND KAUFFHANDELER ZU / BREMEN [HE] HETT IN DISEN / LANDE SINE HANDELING / GEBRUCKET 52 IAHR / IST [ANNO 1573] DEN / 20 AUGUSTI SELIGHT / IN UNSEN HERN ENT / SCHLAPEN DER SEELE GODT GNEDIGH IST.”

Hinrick Segelcken: “ANNO 1585 DEN 25 IULII / UP S. JACOBI IS DE EHRBARE / UND VORNEHME HINRICK / SEGELCKEN DE OLDER UTH / DUDESCHLANT UND BORGER / DER STADT BREMEN ALHIR / IN GODT DEM HERN ENTSCHL / APN DEM GODT GNEDICH IS.”

Helgafell, Iceland

Clawes Lude: “Anno 1585 de.3. Junius starff clawes lüde van Bremen der olde. Dem godt gnedich seij.”

Þykkvabær, Iceland

Hans Berman: “HIR LICHT BEGRAVEN SALICH HANS BIRMA[N] D:I:V:H [i.e. “De Junger van Hamborg”] ANNO 1583.”

Further reading

Hofmeister, Adolf E. Sorgen eines Bremer Shetlandfahrers: Das Testament des Cordt Folkers von 1543. Bremisches Jahrbuch 94 (2015): 46–57.

Holterman, Bart. The Fish Lands. German Trade with Iceland, Shetland and the Faroes in the Late 15th and 16th Century. PhD thesis, Universität Hamburg, 2018.

Koch, Friederike Christiane. Das Grab des Hamburger Hansekaufmanns Hans Berman/Birman in Þykkvibær/Südisland. Island. Zeitschrift der Deutsch-Isländischen Gesellschaft e.V. Köln und der Gesellschaft der Freunde Islands e.V. Hamburg 5.2 (1999): 45.

MacDonald, George. More Shetland Tombstones. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 69 (1934): 27–48.

German merchants at the trading station of Básendar, Iceland

Bart Holterman, 9 March 2018

The German merchants who sailed to Iceland in the 15th and 16th century used more than twenty different harbours. In this post we will focus on one of them: Básendar. The site is located on the western tip of the Reykjanes peninsula and was used as a trading destination first by English ships, then German merchants from Hamburg and later by merchants of the Danish trade monopoly. Básendar is mentioned in German written sources with different spellings as Botsand, Betsand, Bådsand, Bussand, or Boesand.

Aerial image of Básendar (marked with the red star), located on the Western end of Reykjanes peninsula, and Keflavík airport on the right (image Google Earth).

Básendar was one of the most important harbours for the winter fishing around Reykjanes. In the list of ten harbours offered to Hamburg in 1565, it is the second largest harbour, which annually required 30 last flour, half the amount of Hafnarfjörður (the centre of German trade in Iceland). German merchants must have realised it´s potential at a very early stage, and it is therefore the first harbour which we know to have been used by the Germans, namely by merchants from Hamburg, in 1423.

The trading station was located on a cliff just south of Stafnes, surrounded by sand. Básendar was always a difficult harbour, exposed to strong winds and with skerries at its entrance. Ships had to be moored to the rocks with iron rings. The topography of the site also made the buildings vulnerable to spring floods, and during a storm in 1799 all buildings were destroyed by waves, leading to the abandonment of the place. Today, the ruins of many buildings can still be seen, as well as one of the mooring rings, reminding the visitor of the site’s former importance.

Básendar also became a place for clashes between English and German traders. Already the first mention of Germans in the harbour came from a complaint by English merchants that they had been hindered in their business there. In 1477 merchants from Hull complained as well about hindrance by the Germans and in 1491 the English complained that two ships from Hull had been attacked by 220 men from two Hamburg ships anchoring in Básendar and Hafnarfjörður.

The famous violent events of 1532 between Germans and English started in Básendar as well, when Hamburg skipper Lutke Schmidt denied the English ship Anna of Harwich access to the harbour. Another arrival of an English ship a few days later made tensions erupt, resulting in a battle in which two Englishmen were killed. The events in 1532 marked the end of the English presence in Básendar, and we hear little about the harbour in the years afterwards. The trading place seems to have been steadily frequented by Hamburg ships, sometimes even two per year. In 1548, during the time when Iceland was leased to Copenhagen, Hamburg merchants refused to allow a Danish ship to enter the harbour, claiming that they had an ancient right to use it for themselves.

Hamburg merchants were continuously active in Básendar until the introduction of the Danish trade monopoly, except for the period 1565-1583, when the harbour was licensed to merchants from Copenhagen. From 1586 onwards, the licenses were given to Hamburg merchants again. These are the merchants who held licences for Básendar:

1565: Anders Godske, Knud Pedersen (Copenhagen)

1566: Marcus Hess (Copenhagen)

1569: Marcus Hess (Copenhagen)

1584: Peter Hutt, Claus Rademan, Heinrich Tomsen (Wilster)

1586: Georg Grove (Hamburg)

1590: Georg Schinckel (Hamburg)

1593: Reimer Ratkens (Hamburg)

1595: Reimer Ratkens (Hamburg)

The last evidence we have for German presence in Básendar provides interesting details about how trade in Iceland operated. In 1602 Danish merchants from Copenhagen concentrated their activity on Keflavík and Grindavík. A ship from Helsingør, led by Hamburg merchant Johan Holtgreve, with a crew largely consisting of Dutchmen, and helmsman Marten Horneman from Hamburg, tried to reach Skagaströnd (Spakonefeldtshovede) in Northern Iceland, but was unable to get there because of the great amount of sea ice due to the cold winter. Instead, they went to Básendar which was not in use at the time. However, the Copenhagen merchants protested. King Christian IV ordered Hamburg to confiscate the goods from the returned ship. In a surviving document the involved merchants and crew members told their side of the story. They stated that they had been welcomed by the inhabitants of the district of Básendar, who had troubles selling their fish because the catch had been bad last year and the fish were so small that the Danish merchants did not want to buy them. Furthermore, most of their horses had died during the winter so they could not transport the fish to Keflavík or Grindavík and the Danes did not come to them. The Danish merchants were indeed at first not eager to trade in Básendar, and did not sail there until they moved their business from Grindavík in 1640.

Further reading

Ragnheiður Traustadóttir, Fornleifaskráning á Miðnesheiði. Archaeological Survey of Miðnesheiði. Rannsóknaskýrslur 2000, The National Museum of Iceland.