Sailors, merchants and priests: people on board the ships heading North

Bart Holterman, 13 May 2016

The general history of the northern German trade with the North Atlantic is relatively well known but we know very little about the persons involved in this trade. This is especially true for the men that manned and sailed the ships that headed North.

Luckily, there are a couple of sources pertaining to the North Atlantic trade that give us a good insight into the people on board the ships. First, two boarding lists from Oldenburg for ships trading with Iceland in the 1580s have survived. Second, there is the magnificent book of donations of the Hamburg confraternity of St Anne, the socio-religious organisation behind the trade with Iceland, Shetland, and the Faroe Islands. From the 1530s onwards, the register lists the alms spent to the confraternity by the people on board of nearly every ship that returned to Hamburg, resulting in a more or less complete register of boarding lists.

On board a sixteenth-century ship: detail of the epitaph for the ship´s priest Sweder Hoyer (deceased 1565) from the St Jacob church in Lübeck. Note: this image does not necessarily reflect the situation on board the merchant ships in the North Atlantic.

From these sources we can learn that the number of people on board varied greatly, ranging from 77 on larger ships up to around 10 on board the smallest vessels. For Iceland, it was not uncommon to have more than 25 people on board. Ships sailing to Shetland and the Faroe Islands had less people on board, usually 15-20.

This difference in number of people on board was mainly caused by the number of merchants on board. The sizes of the crews were relatively similar on each ship, because 10 to 15 people were needed to sail the ship, regardless of its size. A typical crew consisted of:

– Skipper (schipper). He was the captain, the leader of the ship, often also one of the merchants, and (partly) shipowner.

– Helmsman (sturman), the one who steered the ship and had navigational knowledge.

– Chief boatswain (hovetbosman), the leader of the sailors.

– Schimman, the officer responsible for rigging and other technical things.

– Cook (koch).

– Carpenter (tymmerman), responsible for repairs to the ship.

– Gunner (buchsenschut), responsible for the defense of the ship.

– Barber (bartscher), who had medical knowledge, but lacked on most ships.

– 2-4 sailors (bosman).

– 1-2 ship boys (putker), young sailors in training.

Besides these, ships transported merchants and their servants, falcon catchers, priests, and passengers from the islands which used the regular traffic to travel to and from the European mainland.

Further reading:

B. Holterman, Size and composition of ship crews in the German trade with the North Atlantic islands. In: N. Mehler (ed.), Traveling to Shetland, Faroe and Iceland in the early modern period (Leiden, in press).

F. C. Koch, Untersuchungen über den Aufenthalt von Isländern in Hamburg für den Zeitraum 1520-1662. Beiträge zur Geschichte Hamburgs 49 (Hamburg 1995).

Uncovering the North Atlantic trade sherd by sherd

Natascha Mehler, 12 April 2016

When it comes to the goods transported by merchants from Bremen and Hamburg to the North Atlantic islands we have only limited sources at hand. The few extant account books list the commodities they sold to the inhabitants of the islands in return for stockfish, fish oil, sulphur or woolen cloth. But the written sources are not precise but rather general and never tell where the exported goods were manufactured. To complicate matters, (archaeological) material culture of the German period is scarce. Most of the goods traded by the Germans were bulk material such as grain or flour, cloth, timber, and beer, and to a lesser extent every day items that were hard to get on the islands: horse shoes, tools, knifes, wax etc. Many of these goods, especially those of organic material, have long been gone. Ceramics, however, are a different matter. Icelanders did not produce ceramic vessels (and the Faroese and Shetlanders only to a limited extent) which means that all pots, pans, jugs and beakers needed to be imported. A considerable amount of pottery from the 15th to 17th centuries has been found in Iceland, Shetland and Faroe but what can pottery sherds tell us about that trade?

Fragments of a so called “Schnelle”, a tankard produced in Siegburg in the 16th century, found at Tórshavn, the German trading station in the Faroe islands (photograph by Helgi Michelsen).

The sherds that have survived from excavations and in museum collections in Iceland show characteristic traits of wares common in Northern Europe. The ceramic assemblages of sites such as Gautavík (a German trading site in the East), Viðey (a monastery near Reykjavík), or Stóraborg (a farm at the South coast) consist of two distinctive ware groups: stonewares and redwares. Stoneware was used to produce drinking vessels such as jugs and beakers. They were widely traded over Northern Europe, via the river Rhine and ports of Northern Germany and the Netherlands. For the trained eye, these stonewares are relatively easy to determine. The majority stems from the famous medieval and early modern production centres along the Rhine such as Siegburg, Frechen, or Cologne; a second group can be traced back to Lower Saxony.

The origin of redwares, a general term for cooking vessels (pots, pans) and plates consisting of earthenware, is far more problematic to identify. Vessel shapes and fabrics of pottery workshops are generally very similar over a large area and it is therefore hard to determine where exactly a certain redware pot was produced. Distinguishing the redwares is mostly based on typological characteristics such as a distinctive form of the rim of a pot, but the Icelandic archaeological material is often too fragmented to allow an identification beyond doubts. However, provenancing these redwares would considerably change our understanding of the trade mechanisms and pottery consumption patterns in the North Atlantic.

Fragmented redware tripod with internal lead glaze found at the trading site of Gautavík, Iceland. It dates to the late 16th century but the place of origin remains enigmatic (photograph by Natascha Mehler).

Luckily, there are other methods than typology to identify the provenance of pottery. In recent years, ICP analysis (inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry), widely used in archaeological science, has proven to be a reliable method to determine the chemical fingerprint of the clays used for the production of ceramic vessels. ICP analysis has been applied successfully at a large number of redwares produced in Southern Scandinavia and Germany, with ground breaking work done by Torbjörn Brorsson (Kontoret för Keramiska Studier, Sweden) and Jette Linaa (Moesgaard Museum, Denmark). This means that we now have a solid base of reference material at hand which is necessary to securely identify the origin of the redwares in question. The application of the method in ceramic studies and an overview on the data reference material was presented in April 2016 at the inaugural meeting of the Baltic and North Atlantic Pottery Research Group (BNPG) which took place at the Historiska Museet Stockholm.

In summer 2016, redware fragments from selected sites in Iceland, Shetland and Faroe will be sampled in order to conduct ICP analysis. We will report on the results of the analysis, and what this means for the interpretation of the trading connections between Northern Germany and the North Atlantic islands.

Further reading:

Torbjörn Brorsson, A new method to determine the provenance of pottery – ICP analysis of pottery from Viking age settlements in Northern Europe. In: S. Kleingärtner, U. Müller, J. Scheschkewitz (eds.), Kulturwandel im Spannungsfeld von Tradition und Innovation. Festschrift for Michael Müller-Wille. Neumünster, 2013, 59-66.

Adolf Hofmeister, Das Schuldbuch eines Bremer Islandfahrers aus dem Jahre 1558. Bremisches Jahrbuch 80, 2001, 20-50.

Natascha Mehler, Die mittelalterliche Importkeramik Islands. Current Issues in Nordic Archaeology. Proceedings of the 21st Conference of Nordic Archaeologists, 6-9 September 2001, Akureyri, Iceland. Reykjavik 2004, 167-170.

Manslaughter in the north? the death of Cordt Hemeling on Shetland, 1557

Bart Holterman, 29 January 2016

On a morning in August, 1557, Cordt Hemeling was found dead in his bunk. He was the skipper of a Bremen merchant ship lying at Whalsay in Shetland. The previous evening, Cordt had complained that he was not feeling well and had gone to bed early. After having been found dead the next morning, fingers soon pointed in the direction of two of Cordt’s crew members, Alert Wilckens and the carpenter Gerdt Breker, who as a consequence were accused of manslaughter. Alert and Gerdt, fearing persecution, abandoned ship and fled onto the island where they hid in the wilderness to escape from Cordt’s brother Gerdt Hemeling and the other crew members. As the vegetation on the islands is neither tasty nor very fit for human consumption they were soon starving. Alert was the first to give up, offerring to pay money as compensation and returned to the ship, by which all guilt was transferred to Gerdt Breker. Breker, in fear, tried to keep himself alive by eating the buds of shrubs, but starvation and the threat of being abandoned on the island and of losing his house in Bremen finally drove him back to the ship. He agreed to sign a confession of guilt, and promised to compensate Cordt Hemeling’s family, mortgaging his house.

We would not have known this story if Gerdt Breker had not tried to cancel the agreement upon return to Bremen, where he was expelled from the city. He started a law suit where he claimed to be not guilty of the death of Hemeling, and that he had been forced by his desperate situation to sign a confession against his will. The case and the resulting body of documents, which are still kept in the State Archives in Bremen, give us a unique insight into the life of the merchants and sailors during their stay on the islands, and the relations between them.

Tatort Shetland: the exact location of the fight between Gerdt Breker and Cordt Hemeling is unclear. Gerdt Breker claims that he returned from Laxfirth (Laeßfoerde; blue) with a boat when it happened. Olave Sinclair, the governor of Shetland, states that Hemeling’s ship was lying near Whalsay (red). Both harbours are well-known hanseatic trading sites (map copyright M. Gardiner and N. Mehler).

So what had happened that led Gerdt Breker to be accused of Cordt Hemeling’s death? Apparently there had been a tense situation between Hemeling and his crew for a long time, which erupted when a small boat manned by Alert Wilckens, Gerdt Breker and the helmsman was sent out to shore in Laxfirth to deliver some goods, stayed there longer than planned and returned to the merchant ship late at night. The skipper got angry at his crew members and hit them. Gerdt lost his patience and hit back, thereby breaking two of Cordt’s fingers, after which Alert also hit Cordt, causing him to fall down from the bridge onto the deck. (Note: according to hanseatic sea law, a skipper was allowed to hit his crew once as a disciplinary measure. Gerdt claimed to have been hit by Cordt twice, and was therefore at least theoretically allowed to hit back.)

Cordt, however, seemed to be alright after the fight. Apart from complaining about his fingers, he acted normally for more than a week and took part in the normal activities, including a couple of visits to the shore to fetch sheep, until his sudden death. The exact cause of his death remained unclear. Although Gerdt Breker argued that the injured hand would hardly have led to Cordt’s death, it was the only more or less plausible explanation accepted. Therefore, the Bremen city council did not plea him free from guilt altogether. The council did show some clemency, however. Gerdt could return to the city and his house, and the amount of money he had to pay as compensation to the Hemeling family was lowered.

We do not know what happened to Cordt Hemeling’s body, but it is likely that he was buried at a local church on one of the islands. It is known that other German merchants were buried on Shetland, such as the skipper Segebade Detken, who was also around with a ship when this story happened, and is listed as one of the witnesses in Gerdt Breker’s confession of guilt.

When sailing North, beware of swimming cows and Hamburgers. The Carta Marina and the North Atlantic

Bart Holterman, 5 October 2015

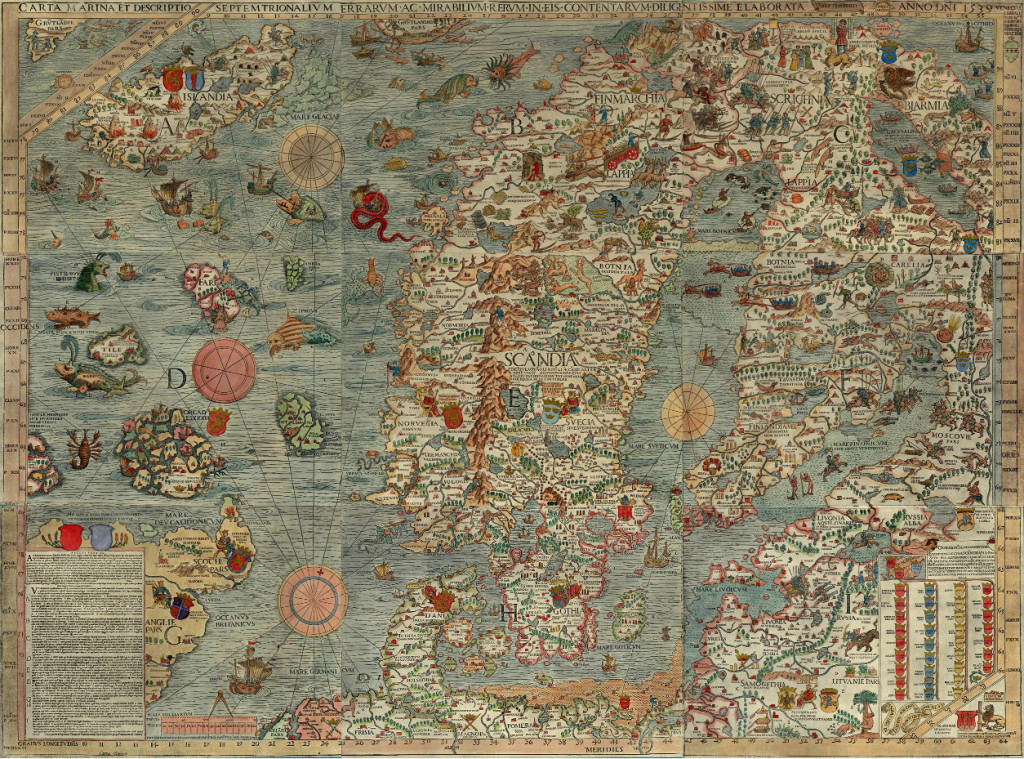

For the banner of this blog and our facebook page, we have displayed a section of the famous Carta Marina from 1539. On a first glance of the map, the many marvellous creatures that inhabit the land and the sea immediately catch the eye of the beholder, yet it also provides us with a good overview of the contemporary North Atlantic trade. Time to explore this remarkable document a bit further.

The map was made by Olaus Magnus (1490-1557), the brother of the last catholic bishop of Sweden. He had travelled Scandinavia and the lands around the Baltic Sea extensively before he was sent on a diplomatic mission to Rome by the Swedish king Gustav Vasa. He was never to return home. Dissatisfied by the Reformation in his homeland, Magnus stayed abroad, first in Lübeck and Danzig, later for a long time in Italy, soon joined by his expelled brother Johannes Magnus. In Italy he kept close contacts to learned men of his age, among others cartographers and travellers.

Under influence from these social circles, Magnus decided to transform his own knowledge about Northern Europe onto a map, which would appear in print in Venice in 1539. It was the first large-scale map of Scandinavia to be ever made, and had much influence on European cartography for the next decades. However, because of its high costs, the number of copies remained low. The map itself disappeared off the map of European learning, and was deemed to be lost since the late sixteenth century. Luckily in 1886 an intact copy of the map was discovered in the Bavarian State Library in Munich, and in 1961 another one, which now resides in Uppsala.

An explanation of the map appeared only in 1555 as Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus. In this book, Olaus Magnus described the geography, wildlife, and customs of the people of the North, illustrated with woodcuts. These woodcuts are clearly based on parts of the map, which includes many details about the people of the North, the political situation of the time, and the nature and wildlife. We can see kings sitting on their thrones, armies crossing the frozen Baltic Sea, people hunting seals, the most important towns and cities, lighthouses, whales attacking ships, enormous snakes, swimming cows and other sea monsters.

The map is divided into nine parts, marked A-I. It covers the entire Scandinavian peninsula, the Baltic, Northern Germany and the Netherlands, the entire North Sea and North Atlantic, including the coastline of Britain, the southern tip of Greenland and the mythical island Thule, known from classical geographical works. Of our interest are mainly the sections A and D, covering a large part of the North Atlantic.

Olaus Magnus probably never visited the North Atlantic himself. Instead, he had to rely on the stories and descriptions of others, for example the Northern German traders that told him about Iceland, the Shetlands and the Faroe Islands. Of the Shetlands and Faroes, Magnus must have had few information, as these archipelagos are only schematically drawn. One remarkable detail can be found on the Faroes, though, where we can see a whale being slaughtered on the shore, reminiscing a practice of hunting whales by driving them up the shore which is still practiced today.

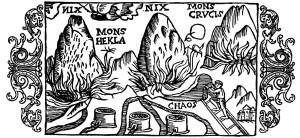

For Iceland, Magnus was clearly better informed. The Carta Marina was the first map that drew the island in its more or less actual shape. Moreover, three vulcanoes attest to Magnus’s knowledge of the high vulcanic activity on the island. The two episcopal sees, Hólar (Holensis) and Skálholt (Scalholdin), are displayed, as well as the monastery Helgafell (Abbatia Helgfiall), which was famed for its butter production (butirum). The three knights on the eastern part of Iceland should probably be seen as an indication of Danish military presence on the island.

Three volcanoes on Iceland, from Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (1555), photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Better than the natural, religious, and political situation, the map attests of the economic situation. Firstly, the main export goods of Iceland are indicated. These are, besides the already mentioned butter: stockfish, sulphur, and falcons. Stockfish was dried cod, highly valued in Europe as a preservable source of protein, and the main trade good of the arctic region. It is shown on a pile on the south coast. Just north of it, three containers of sulphur are depicted. Iceland was one of the few places where pure sulphur could be found. Sulphur, being among others a key ingredient for making gunpowder, was a highly valued substance. Finally, a gyr falcon (falco albus) can be seen on one of the northern peninsulas of Iceland. Gyr falcons are only found in arctic regions, and due to its being the largest and strongest species of falcon, it was highly valued by the nobility for use in falconry.

Apart from the export goods, the realities of the north atlantic trade are displayed in considerable detail on the map. Various trading harbours are indicated, most notably Hafnarfjörður (Hanafiord), where merchants from Hamburg had built a church. We can see ships lying at anchor at these harbours, and three tents at Ostrabord, which probably indicate the temporary booths the merchants set up on the shore and where they displayed their goods on sale during the summer.

The most important countries and cities trading with the island are also indicated. We can see a ship from Bremen at anchor near Ostrabord, an English ship which confused a whale for an island, a ship from Lübeck being attacked by whales, and a Scottish ship under attack by one from Hamburg, indicating the dominance of Hamburg in the North Atlantic trade. It was no exception that competition between merchants from different places led to violent clashes, as in 1523, when the crews of ships from Bremen and Hamburg attacked an English ship in a conflict over the rightful ownership of an amount of stockfish, resulting in casualties among the English.

These elements make the Carta Marina a wonderful visual testimony of the North Atlantic trade in the sixteenth century.

Posted in: Sources