Brüning Rulves

Bart Holterman, 9 February 2023

In the collection of the Focke-Museum in Bremen, there exists a portrait of a stern-looking old bearded man, clothed in black, with in his hands a small red booklet and a handkerchief. The portrait is dated 1597, and surrounded by angels and a seascape with ships flying Dutch, Danish and Bremen flags, which is probably a later addition. The portrait is believed to represent Brüning Rulves, a retired skipper from Bremen who became famous for his memoirs, which give a rare detailed insight into the career of a 16th-century seafarer.

Regrettably, the booklet in which he kept his memoirs has been lost since the Second World War, but at least the portrait probably shows what it looked like, as the red booklet in Rulves’ hand could very well be the said memoirs. Moreover, there exists a summary and partial transcription of the book in an article from Johann Focke, the leader of the museum, from 1916. Focke translated the cited passages from the original Low German text into modern High German in his article. However, the original transcripts that Focke made from the book in order to compile his article have been preserved in the museum archives, so not all is lost.

From what Focke wrote about the book, we know that Rulves started his career at sea at the age of twelve, when he was first employed on a ship by his stepfather. At the age of 33, he had acquired enough experience as a sailor and helmsman to work as a skipper on his own ship and he continued to sail as a skipper until he retired at the age of 55. His many voyages took him all across northern Europe, from Portugal to Bergen in Norway and the Baltic Sea. After his retirement he became one of the first inhabitants of the Haus Seefahrt, a social security organisation for skippers and their families founded in 1545, which exists to this day.

The Haus Seefahrt had strong connections with the North Atlantic trade of the city of Bremen. In the foundation document it is mentioned that the merchants sailing to the “fish lands” Bergen, Iceland and Shetland used to make donations to the church after their safe return home to Bremen, but had stopped doing that since the Reformation. Now these funds were to be put to good use to care for their poor colleagues. Moreover, one of the eight founding members and elderman in 1563, Herman Wedeman, was active as a merchant in Iceland himself.

But Brüning Rulves himself was no stranger in the North as well. He sailed many times to Bergen and once, in 1551, to Shetland, after another ship had been shipwrecked. Curiously, his memoirs mention the said journey twice, on different pages, in slightly different wordings:

p. 46

“Ao. 1551. do vorfrachtede Johan Baller Hynrich van Mynden (als Johan Reyners was bleven up harfest ao. 50; was Johan Baller schip, dar se mede in Hytlant plach tho segelen, bleff ock myt man und all. Godt sy der sele gnedych) legen? van de Weser van Blexsen up eyn mandach, des donnerdages quamen wy gudt tydt in Hytlant in den Brusunt.”

p. 73

“Ao. 1551. do frachtede Johan Baller schipper Hynrich van Mynden up Hytlant, lach in Borchwage (als Johan Baller schipp was dat forige harvest ao. 1550 bleven myt soltfyske, wolde syn in Englant und Johan Reyners was dar sethschipper up, blif myt man und alles) und ick Brunynck Rulves was do myt segelt in Hytlant ao. 1551.”

Although the statements differ in small details, the general meaning is similar: Johan Ballers had freighted the ship of Johan Reyners in 1550, who was supposed to sail to Shetland to buy fish and sell them in England, but wrecked in Autumn and all on board drowned. The next year, Ballers freighted the ship of Hynrich van Mynden to sail to Shetland, and Brüning Rulves sailed with him.

Johan Ballers already appears in Shetland in a document about the sale of land in Shetland from 1539, which mentions that one of the reasons for the sale of the land was that Thomas Hacket, the owner of the land, had inherited from his late brother Robert, who had taken up credit from Ballers. A document from 1562 also refers to trade of Bremen merchants in the harbour Baltasound in Shetland “in Johan Baller’s time”. Apparently, Ballers had first traded in Shetland as a skipper himself, but by the middle of the 16th century he remained at home, providing his capital as a freighter in the trade with Shetland.

Brüning Rulves’ portrait is part of the exhibition “Immer Weiter – die Hanse im Nordatlantik”, which will be shown in the German Maritime Museum from 23 March 2023.

Further reading

Focke, Johann. ‘Das Seefahrtenbuch des Brüning Rulves’. Bremisches Jahrbuch 26 (1916): 91–144. https://brema.suub.uni-bremen.de/periodical/pageview/35267

Relevant documents in HANSdoc: https://hansdoc.dsm.museum/Hansdoc.php?varPerson=48&varSearch=people2

A greasy business: the trade in Shetland butter

Bart Holterman, 18 December 2021

Among the commodities exported from the North Atlantic islands in the late Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, few are as enigmatic as butter. As rents and taxes were partly paid in butter on the islands, they frequently appear as a trade item in the dealings of the authorities or the church with foreign (German) merchants. However, the role of butter in the North Atlantic trade is not well understood.

On the Carta Marina of Olaus Magnus of 1539, barrels of butter are displayed near the monastery Helgafell in Iceland, indicating the significant butter production of the Icelandic church (see the header image of this blog). Magnus described in his 1555 Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus that salted butter was produced in Iceland “partly for consumption at home, but more particularly for barter with merchants”. It is indeed known that German merchants bought butter in Iceland, but but they imported butter to Iceland as well, which is puzzling. Probably, this was butter of a different quality, but the sources do not say much about it. Butter exports are also known for the Faroes in the late 16th century.

Where the relevance of butter as a foreign exchange product was probably limited in Iceland and the Faroes, it seems to have played a much more prominent role in Shetland and Orkney. Especially in the 17th century, there are frequent mentions of German merchants buying butter from Shetland sheriffs, lairds or tacksmen. On many occasions, they even entered into considerable debts for taking the butter to Germany.

This is remarkable, given that the export butter from Shetland and Orkney does not seem to have been of a specifically good quality. Farmers kept the better quality “meat butter” for home consumption, whereas the butter with which taxes and rents were paid was the low quality “grease butter”, full of hairs and dirt, unfit for consumption. According to Gordon Donaldson, it “was fit only for greasing wagon-wheels”. It was exactly this grease butter that was sold abroad. Already in the 16th century, it is known that salted Orkney butter was sold very cheaply in Scotland.

On a more closer look, it seems that the German merchants in Shetland were not so keen on buying the Shetland butter, even though they bought it in considerable quantities. Various letters of the 17th century tell about the negotiations of Shetland tacksmen and the servants of lairds with German merchants about the price of butter. For example, James Omand wrote to Laurence Sinclair of Brugh in 1640 that he could only sell the butter to the Germans for a lower price than expected. Two letters from Andro Greig to the Baron of Brugh from 1655 mention his dealings with Hamburg merchant Otto Make, who was not interested in buying butter for the reason that he could not get a good price for it on the German market. The letters of the tacksmen Andro Smith to his brother Patrick from the early 1640s also speak of the difficulties he had with selling the butter to the German merchants; he had to sell the butter in Leith in the end.

Even more explicit is a letter from David Murray to Andrew Mowat from 1682, in which Murray instructs Mowat to “use all possible means” to make the German merchants take the Shetland butter. This included threatening them, although he also presses him “to deall civellie with them”.

All in all, it appears that Shetland officials did not always have an easy time trying to sell the butter abroad. It also remains the questions why the Germans took the butter with them after all, especially since good-quality butter was produced in northern Germany as well, for example in East Frisia. Were the Germans exaggerating and only playing hard-to-get to keep the prices low? Did they give in to the pressure that the Shetlanders put on them? Or did they perhaps feel obliged to take parts of the butter from their trading partners for fear of losing access to the much more profitable Shetland fish trade, even if they could only sell it at a loss? It seems that further research will be needed to solve this riddle.

References and further reading

Ballantyne, John H., and Brian Smith, eds. Shetland Documents, 1612-1637. Lerwick, 2016.

Donaldson, Gordon. Shetland Life under Earl Patrick. Edinburgh, 1958.

Fenton, Alexander. The Northern Isles: Orkney and Shetland. Edinburgh, 1978.

Holterman, Bart. The Fish Lands. German Trade with Iceland, Shetland and the Faroe Islands in the Late 15th and 16th Century. Berlin, 2020.

Posted in: General, Sources, Stories

Till death do us part: Graves of sixteenth-century German merchants in the North Atlantic

Bart Holterman, 11 October 2018

When one has the chance to visit the northernmost island of Shetland, Unst, it is worth visiting the ruined church at Lunda Wick, in a bay to the Southwest of the isle. To get there, one has to take a small gravel road across a barren moory landscape where nothing seems to live but sheep and the occasional marsh bird. At the end of the path, one reaches a secluded bay where the grey waves and the rain torture the sands of the beach, and out of the fog a ruined medieval chapel appears with a graveyard around it. Inside the roofless chapel are a number of old tomb stones, the text made almost illegible by the lichen that overgrows them and centuries of rain and salty sea wind. In a corner lies a grave slab, on which it is possible to discern a text written in Low German, with great difficulty: “Here lies the honourable Segebad Detken, citizen and merchant from Bremen, who has traded in this country for 52 years, and died [in the year 1573], the 20th of August. God have mercy on his soul” (see below for the Low German text).

Segebad Detken is known from written sources about the Bremen trade with Shetland. He can be tracked from 1557 onwards as a skipper in the northern harbours Burravoe in Yell, and Baltasound and Uyeasound in Unst. In 1566, he was robbed by Scottish pirates in the harbour of Uyeasound. As his tomb slab mentions that he had been trading for 52 years in Shetland, he must have died in the late 16th century (see below). After his death, his relatives took over the business: among others his son Herman and grandson Magnus are recorded as merchants in northern Shetland in the early 17th century.

The grave slab of Segebad Detken in the ruined church in Lunda Wick. Photograph: Bart Holterman, 2018.

Given the long careers of German traders in the North Atlantic, and the fact that Bremen and Hamburg merchants dominated this trade for over 100 years (for Shetland even longer), it is not surprising that some of these merchants were buried on the islands when they died there. We can find another example just a bit outside the same church. There is another grave of a contemporary of Segebad Detken, that of his fellow citizen Hinrick Segelken. The Low German text on his slab translates as: “In the year 1585, the 25th of July, on St James’ day, the honourable and noble Hinrick Segelcken the Elder from Germany and citizen of the city of Bremen, died here in God our Lord, who has mercy on him.”

The tombstones were most probably imported by the German merchants, as the sandstone from which they were made is not available on the islands. By erecting a distinct grave marker for their deceased colleagues, they did not only honour their remembrance, but it also served to strengthen their ties with the local communities. The material and textual aspects of the monuments reminded the observer of the importance of the German merchants for the local economy, even across the boundaries of life and death.

A similar situation we find on Iceland, where we can also find tombstones of German merchants. The National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavik, for example, houses the tomb slab of Bremen merchant Claus Lude (follow link for an image), who was originally buried in the monastery Helgafell on the Snæfellsnes peninsula. The stone shows his house mark, a seal with two crossed stockfishes, and a text which mentions that he died on 3 June 1585. Lude is known to have been active in harbours in Snæfellsnes in the 1550s, and held a license for the harbour Grindavík in 1571.

In southern Iceland, at the graveyard of the former monastery Þykkvabær, one can still find the tombstone of Hans Berman the Younger from Hamburg, who died in 1583. The monastery records reveal that he was administrator of the monastic property (klausturhaldari) and was killed by the parish priest of Mýrar. His name also appears in the register of the Confraternity of St Anne of the Iceland merchants in Hamburg, where another Hans Berman (probably his father) was elderman around the same time.

In Hafnarfjörður near Reykjavík, the Hamburg merchants had their headquarters and also erected their own church. It is likely that they also had a graveyard where they buried their dead. During construction of the modern harbour of Hafnarfjörður in the 1940s, human bones were found which many believed to be from the old German graveyard in the town. It might even be possible that these bones once belonged to Hamburg merchant Hans Hambrock, the only death of a Hamburg merchant in Hafnarfjörður known from the written record. Hambrock had died from the injuries inflicted upon him by his colleague Hinrick Ratken, who drew his knife against him after Hambrock had hit Ratken on the head during a conflict about the unloading of a ship in 1599. Regrettably, the remains of the German church in Hafnarfjörður are now buried below the modern town.

Inscriptions on the discussed tombstones

Lunda Wick, Shetland

Segebad Detken: “HIR LIGHT DER EHRSAME / SEGEBAD DETKEN BVRGER / VND KAUFFHANDELER ZU / BREMEN [HE] HETT IN DISEN / LANDE SINE HANDELING / GEBRUCKET 52 IAHR / IST [ANNO 1573] DEN / 20 AUGUSTI SELIGHT / IN UNSEN HERN ENT / SCHLAPEN DER SEELE GODT GNEDIGH IST.”

Hinrick Segelcken: “ANNO 1585 DEN 25 IULII / UP S. JACOBI IS DE EHRBARE / UND VORNEHME HINRICK / SEGELCKEN DE OLDER UTH / DUDESCHLANT UND BORGER / DER STADT BREMEN ALHIR / IN GODT DEM HERN ENTSCHL / APN DEM GODT GNEDICH IS.”

Helgafell, Iceland

Clawes Lude: “Anno 1585 de.3. Junius starff clawes lüde van Bremen der olde. Dem godt gnedich seij.”

Þykkvabær, Iceland

Hans Berman: “HIR LICHT BEGRAVEN SALICH HANS BIRMA[N] D:I:V:H [i.e. “De Junger van Hamborg”] ANNO 1583.”

Further reading

Hofmeister, Adolf E. Sorgen eines Bremer Shetlandfahrers: Das Testament des Cordt Folkers von 1543. Bremisches Jahrbuch 94 (2015): 46–57.

Holterman, Bart. The Fish Lands. German Trade with Iceland, Shetland and the Faroes in the Late 15th and 16th Century. PhD thesis, Universität Hamburg, 2018.

Koch, Friederike Christiane. Das Grab des Hamburger Hansekaufmanns Hans Berman/Birman in Þykkvibær/Südisland. Island. Zeitschrift der Deutsch-Isländischen Gesellschaft e.V. Köln und der Gesellschaft der Freunde Islands e.V. Hamburg 5.2 (1999): 45.

MacDonald, George. More Shetland Tombstones. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 69 (1934): 27–48.

German merchants at the trading station of Básendar, Iceland

Bart Holterman, 9 March 2018

The German merchants who sailed to Iceland in the 15th and 16th century used more than twenty different harbours. In this post we will focus on one of them: Básendar. The site is located on the western tip of the Reykjanes peninsula and was used as a trading destination first by English ships, then German merchants from Hamburg and later by merchants of the Danish trade monopoly. Básendar is mentioned in German written sources with different spellings as Botsand, Betsand, Bådsand, Bussand, or Boesand.

Aerial image of Básendar (marked with the red star), located on the Western end of Reykjanes peninsula, and Keflavík airport on the right (image Google Earth).

Básendar was one of the most important harbours for the winter fishing around Reykjanes. In the list of ten harbours offered to Hamburg in 1565, it is the second largest harbour, which annually required 30 last flour, half the amount of Hafnarfjörður (the centre of German trade in Iceland). German merchants must have realised it´s potential at a very early stage, and it is therefore the first harbour which we know to have been used by the Germans, namely by merchants from Hamburg, in 1423.

The trading station was located on a cliff just south of Stafnes, surrounded by sand. Básendar was always a difficult harbour, exposed to strong winds and with skerries at its entrance. Ships had to be moored to the rocks with iron rings. The topography of the site also made the buildings vulnerable to spring floods, and during a storm in 1799 all buildings were destroyed by waves, leading to the abandonment of the place. Today, the ruins of many buildings can still be seen, as well as one of the mooring rings, reminding the visitor of the site’s former importance.

Básendar also became a place for clashes between English and German traders. Already the first mention of Germans in the harbour came from a complaint by English merchants that they had been hindered in their business there. In 1477 merchants from Hull complained as well about hindrance by the Germans and in 1491 the English complained that two ships from Hull had been attacked by 220 men from two Hamburg ships anchoring in Básendar and Hafnarfjörður.

The famous violent events of 1532 between Germans and English started in Básendar as well, when Hamburg skipper Lutke Schmidt denied the English ship Anna of Harwich access to the harbour. Another arrival of an English ship a few days later made tensions erupt, resulting in a battle in which two Englishmen were killed. The events in 1532 marked the end of the English presence in Básendar, and we hear little about the harbour in the years afterwards. The trading place seems to have been steadily frequented by Hamburg ships, sometimes even two per year. In 1548, during the time when Iceland was leased to Copenhagen, Hamburg merchants refused to allow a Danish ship to enter the harbour, claiming that they had an ancient right to use it for themselves.

Hamburg merchants were continuously active in Básendar until the introduction of the Danish trade monopoly, except for the period 1565-1583, when the harbour was licensed to merchants from Copenhagen. From 1586 onwards, the licenses were given to Hamburg merchants again. These are the merchants who held licences for Básendar:

1565: Anders Godske, Knud Pedersen (Copenhagen)

1566: Marcus Hess (Copenhagen)

1569: Marcus Hess (Copenhagen)

1584: Peter Hutt, Claus Rademan, Heinrich Tomsen (Wilster)

1586: Georg Grove (Hamburg)

1590: Georg Schinckel (Hamburg)

1593: Reimer Ratkens (Hamburg)

1595: Reimer Ratkens (Hamburg)

The last evidence we have for German presence in Básendar provides interesting details about how trade in Iceland operated. In 1602 Danish merchants from Copenhagen concentrated their activity on Keflavík and Grindavík. A ship from Helsingør, led by Hamburg merchant Johan Holtgreve, with a crew largely consisting of Dutchmen, and helmsman Marten Horneman from Hamburg, tried to reach Skagaströnd (Spakonefeldtshovede) in Northern Iceland, but was unable to get there because of the great amount of sea ice due to the cold winter. Instead, they went to Básendar which was not in use at the time. However, the Copenhagen merchants protested. King Christian IV ordered Hamburg to confiscate the goods from the returned ship. In a surviving document the involved merchants and crew members told their side of the story. They stated that they had been welcomed by the inhabitants of the district of Básendar, who had troubles selling their fish because the catch had been bad last year and the fish were so small that the Danish merchants did not want to buy them. Furthermore, most of their horses had died during the winter so they could not transport the fish to Keflavík or Grindavík and the Danes did not come to them. The Danish merchants were indeed at first not eager to trade in Básendar, and did not sail there until they moved their business from Grindavík in 1640.

Further reading

Ragnheiður Traustadóttir, Fornleifaskráning á Miðnesheiði. Archaeological Survey of Miðnesheiði. Rannsóknaskýrslur 2000, The National Museum of Iceland.

Where have all the ships gone? The absence of German shipwrecks in Iceland

Bart Holterman, 22 December 2017

Mike Belasus, with Kevin Martin and Bart Holterman

Detail from Olaus Magnus Carta Marina 1539: The ship-destroying sea monster is symbolising the perils of a journey across the open ocean.

A Project on the Low German merchants’ trade from Bremen and Hamburg with the North Atlantic islands is not complete without the vessels that made trade across the ocean possible. The written sources tell us that many German ships were lost along the coast of Iceland, but until today, not a single mentioned shipwreck was found. This is not surprising, given the circumstance that underwater archaeology in Iceland is not even twenty years old.

Some facts about finding shipwrecks

The saying “Searching for a needle in a haystack” is fitting pretty well to the search for shipwrecks mentioned in historical documents, considering the abilities to determine a ship’s position in the past and the fact that 71 % of Earth’s surface is covered by water. Even today, many ships vanish without a trace. On top of that, the number of archaeologists looking for certain shipwrecks is extremely low. Therefore, most shipwrecks are found by accident and they remain more or less anonymous.

However, technology has improved and the potential for finding shipwrecks is much higher today than in the past. A number of devices can be used and combined for surveying the sea floor. A common combination is a side-scan sonar and a number of magnetometers, but this is still no guarantee for finding wrecks. When a ship is too decayed, or has settled into the sediment, the sound-rays of the side-scan sonar will not be able to produce a recognisable image. Moreover, magnetometers will not detect anomalies from the earth’s magnetic field when there is not enough metal on board the ship. Especially for medieval ships and early modern merchant vessels without guns, this can easily be the case. A sediment sonar could be a solution, which measures changes of density in the sediment with sound signals. The disadvantage is that waterlogged wood has the same density as waterlogged sediment. If a shipwreck has no denser cargo or ballast on board, the sonar will not detect density changes. Therefore such ships will remain hidden, even if an area is surveyed. Divers might be suggested as a final solution but a diver’s operating range is very limited, as he/she depends on depth, weather conditions, visibility and air supply.

The fact is that archaeologists rely in most cases on coincidences, which is how most of the known shipwrecks were found. The reason for this is that many other professions like builders, fishermen, geologists etc. spend much more time working on the sea floor than archaeologists, and sometimes stumble upon a wreck. One famous example for this is for example the “Bremen Cog” in the German Maritime Museum in Bremerhaven. A suction-excavator operator found it in the river Weser close to Bremen, when he was working on an extension of the riverbed. It became one of the most important finds in ship archaeology. Over the past decades, since underwater became an area of archaeological interest, hundreds of shipwrecks have been registered by the heritage departments of the German federal states but only a few of them could be identified by historical documents.

The author examining an anchor off the west coast of Gotland, at the site of the Visby-Disaster of 1566 (Photo: Jens Auer).

When we approach the shipwrecks from the historical documents, we have to realize that mentioned positions for lost ships are most of the time very vague. This situation can extend the search area dramatically without even knowing if the wrecks still exist as a coherent site. The conditions of the natural environment are vital to the survival of remains. Rugged coastlines, strong currents, micro-organisms, the chemical consistence of the water and the like can severely contribute to the decay of organic matter, metals and even certain types of stone. In the Mediterranean Sea, for example, ship hulls will not survive for a long time above the sea floor due to temperature, salinity and micro-organisms. Iron will soon vanish by the reaction with salt and oxygen and even marble and copper-alloys will decay. The opposite situation can be found in the Northern Baltic or the Sea Black Sea, for example. The Northern Baltic is deep, has a very low salt content and is cold. This prevents wood-decaying organisms to multiply and destruction from anchors or looting divers. The Black Sea water, on the other hand, has hardly any oxygen in a certain depth, which almost freezes time on the sea floor.

In addition, the circumstances of the sinking in connection to the natural environment play an important role. A German ship in Spanish service in 1588, the Gran Grifon, hardly left any structural remains. Another extreme example is the destruction of a united navy fleet of Lübeck and Danish ships during the Nordic Seven Years War on the west coast of Gotland in 1566. Out of thirty-seven ships, fifteen were lost and 6000 to 8000 sailors lost their lives in the so-called Visby-Disaster. Intensive archaeological diving surveys for several years could not reveal any wreck site. The ships literally vanished, most likely because they disintegrated in the storm on the rough sea floor and their remains were thrown up on the beach.

These examples shows us that a sunken ship mentioned in the historical documents does not always leave a proper wreck site. Sometimes scattered debris spread over square kilometres of sea floor can be all that is left of a ship.

The missing wrecks of Iceland

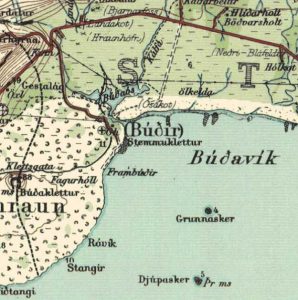

The site of the Bremen trading harbour Búðir/Bodenstede on the west coast of Iceland. It continued to be used by the Danes after 1601.

In theory, Iceland has a high potential for finding shipwrecks. Since the late 9th century, humans settle here and they had no other way than to cross the rough North Atlantic Ocean and make landfall on a rugged coast. Many ships, Norwegian, Danish, English, Low German and Dutch, evidently got lost on their route between continental Europe and Iceland. A considerable number of these found their end on the coast of Iceland, as we can read in the historical documents. Ragnar Edvardson has calculated a number of about 450 shipwrecks in Iceland, from the period from 1100 to 1900, most of which foundered on the West coast. Until today, no wreck from the period of the Low German trade has been found. The oldest ship found in Iceland is currently a Dutch merchantman, which sank in the harbour at Flatey in Breiðafjörður in 1659, and is currently under investigation by Kevin Martin. The scarcity of known shipwrecks in Iceland is not necessarily because they vanished completely, but because maritime archaeology is a very young discipline in this country and started only with sporadic projects from 1993 onwards. The relatively few inhabitants of Iceland also reduce the possibility of coincidental discoveries of wrecks due to the lack of building activities.

Vive la Coïncidence!

However, coincidences happen – even in Iceland. In 1998, an excavator hit timbers while digging a cable trench near Búðir on the Snæfellsnes peninsula in Western Iceland. They turned out to be fragments of a ship that was buried under the sand of an estuary. Some timbers and ballast stones were recovered by archaeologist Björn Stefánsson, and brought to the National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavik, were they were documented and put in storage. None of the recovered timbers was suitable for dendrochronological dating, but the ballast included stones that can possibly originate in Norway, Britain or Greenland. However, this does not give any indication were the ship was coming from, because ballast was taken from board and loaded in all harbours depending on the cargo and to adjust the angle of the ship in the water, to trim the ship. The recovered timbers give the impression of an old carvel-built ship. The material seems not to be of the finest quality, but this is hard to judge from only a handful of timbers. A promising fact is that Búðir was an important trading centre in Iceland for at least 200 years. It was already visited by Bremen merchants in the late 16th century, who called it “Bodenstede”. For a long time it was the main trading site for the Snæfellsness Peninsula, called first by cargo ships of the Low German merchants and later by Danish and Dutch ships. It was abandoned as a trading post in 1787.

The recovered ship timbers from Búðir today at the National Museum of Iceland, Reykjavik (Photo: Kevin Martin)

For this reason, we have written sources on the activities on this site including the loss of several ships during these 200 years. The problem for the identification of the accidental found ship is the fact that there was not only one ship lost near the site. We know at least about eleven ships that are reported to have been lost at Búðir and its harbour Búðavik. Of those eleven ships, one was from Bremen. It belonged to the merchant Vasmer Bake and sank in or close to the harbour of Bodenstede in 1587. This was reported by Carsten Bake, his son, who himself was involved in the Iceland trade. In 1607, a Danish ship wrecked at Búðir. For 1666, another ship sank west of Búðir. More ships sank in this area in 1724, 1728 (Danish) and 1754, and lastly, Bjarni Sívertsen’s cutter, which got lost here in 1812.

Certainly, it is possible that the ship found in 1998 is Vasmer Bake’s lost vessel from 1587, but the timbers cannot give us any more detailed information. All we can say today about the few recovered timbers is that there are five floor timbers and two fragments with an unknown function. The floor timbers indicate that the cable trench hit the wreck most likely in the bow section, leaving most of the buried remains uncovered. Each plank was attached to each frame with at least two tree nails, and each frame was connected to the keel with one or two tree nails. The dimensions of the floor timbers vary a lot, from flat and wide to high and narrow. This might be an indication that whoever built the ship faced either a shortage of crooked compass timbers, or the building did not rely on an even framing in a shell based building method, or both. However, it can also not be excluded that we face the remains of Bjarni Sívertsen’s cutter from 1812. Only future investigations might give us an answer.

References:

Edvardson R. and Grassel Ph., The Potential of Underwater Archaeology in the North Atlantic. In: N. Mehler, Travelling to Shetland, Faroe and Iceland during the 15th to 17th centuries (in press).

Stefànson, B., Skipsviðir úr Búðaósi. Rannsóknaskýrslur fornleifadeildar 1998. Fornleifadeild þjóðminjasafns Íslands, Reykjavik 1998

Posted in: General, Reports, Stories